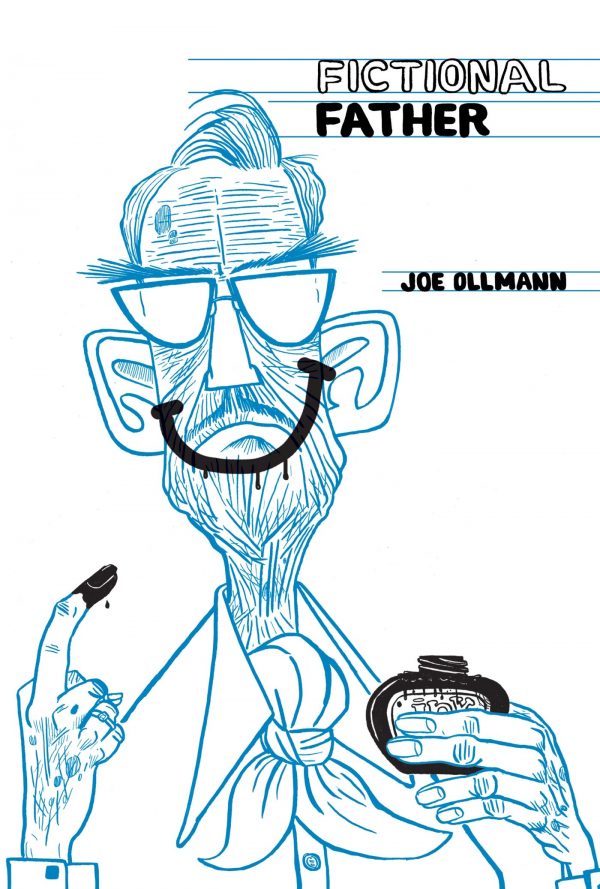

Fictional Father

By Joe Ollmann

Drawn and Quarterly

In the world of comics, I’ve always felt like Joe Ollmann inhabited his own space, but I’m not sure I can cohesively define what that space is. The Joe Ollmann space, I guess, which loosely consists of a sprawling story of domestic drama portrayed through a dark sense of humor that is sometimes negative and even outright hostile, always centering on a white male, usually middle-aged or thereabouts, with traits and actions that make him anything from best not to get too involved with to entirely reprehensible, and almost always the cause of his own problem.

There is also an aspect to Ollmann’s work that makes the stories seem autobiographical even though they’re not and even though the main characters tend to have some physical resemblance to the cartoonist who creates them even though they’re not him, not even remotely. It’s a peculiar niche, to be sure, but it’s one that Ollmann has mastered in such a way that anything he puts out is worth grabbing. He doesn’t try to be anyone else, he just tries to be himself.

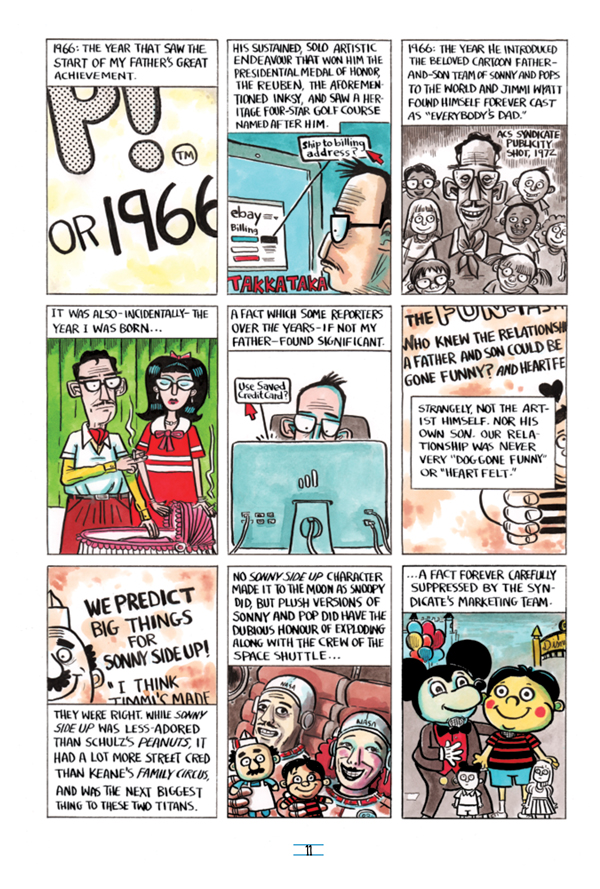

That’s actually part of the central mantra that lurks around Fictional Father, which follows the hapless Caleb Wyatt as he tries to find some peace with his life but can’t, partly thanks to his famous cartoonist father and partly thanks to his own inability to follow through or make the right decision or just settle.

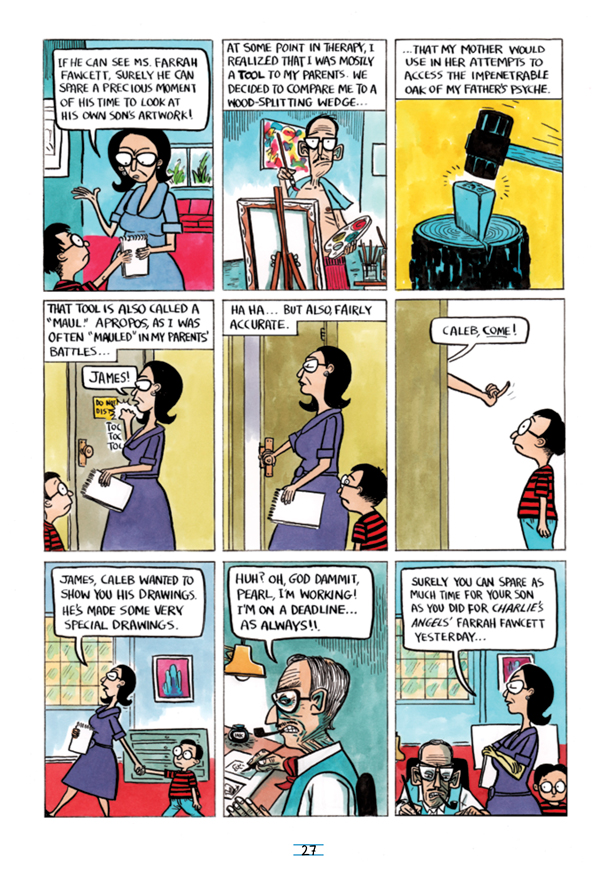

His dad Jimmy is the mastermind behind the newspaper strip Sonny Side Up, an excruciatingly sentimental and trite comic that features corny humor built around how much the father in the strip loves his son. Caleb grew up with Sonny Side Up as part of the air he breathed, even though his father in no way resembled the father in the strip and was, in fact, the exact opposite — a cruel, womanizing, largely absent, booze-slurping jerk who in Caleb’s memory rarely had time for a kind word or even a fatherly moment with his son.

As with any dysfunctional family, Caleb’s mother renders the other side of his childhood trauma. Even as the wronged party she uses her own hurt to commandeer Caleb as an agent in the war against the man she married and who actively worked to make her life miserable.

Caleb, a failed cartoonist and successful AA devotee, recounts his life and traumas for the first half of Fictional Father, while in the second he seizes an opportunity to redeem his life, or find out who he is, or face his demons. He isn’t quite sure, but he does it anyhow.

As always with Ollmann, there is much humor to be had from an unfortunate failure of a life and the victimhood of the narrator who lived that life, and Ollmann also does well to make an examination of the character’s privilege as a component of all that. And as usual, it’s presented with a fair amount of sympathy for the person who is unraveling the misfortune, part of that treadmill anyone can find themselves on while trying to map out that difficult section of one’s life where you differentiate between the trauma that was thrust on them and the hurt they thrust on other people. What was caused by the former and what was their own doing? And how much does any of that really matter anyhow?

And though Fictional Father is specifically about living under the shadow of a famous parent, it is, at its core, about living with the reality of any parent. We all end up as some sort of strange mix of our parents and our reactions against our parents, and any aspect of that concoction manifests at different points and times and situations, and it’s hard to know which it is and what you do about it. That combination steers how we treat others and how we conduct ourselves and it can be a lethal mix in some situations. It’s certainly a confounding one in many situations.

In Caleb’s case, a lot of it is whining — it’s not that he wasn’t wronged in his childhood, it’s that he’s become used to voicing his complaints but never really got to the point of correcting their effect on him. The great thing about art is, well, that’s what it’s for, really. Whining. But you get it out in a productive way that sometimes creates something worthwhile out of your pain and irritation, partly from keeping it from driving loved ones crazy and partly by putting it in a form that allows for contemplation and evolution on the subject. And that’s a lot of what Ollmann is heading towards in Fictional Father.

But there’s also a counter-question that’s harder to answer. If Caleb’s answer is to seek out honest, therapeutic creativity, what does that mean for the work his father did? Are we to believe this schmaltzy cartoon was who he really was? Was it a reflection of his own experience? Was it dream fulfillment for a terrible experience? Did it have anything to do with his own experience? Was it honest at all?

Or does any of that really matter? What is plain is that Caleb’s horrible father spread joy that millions of people embraced as something personal to them. Is that the ultimate secret? Caleb’s father knew what people needed even if he was incapable of giving it to his family? We’ll never know. People are complicated and we often know only certain parts of them. In the end, the only person you really need to know is yourself, and Ollmann truly understands that.