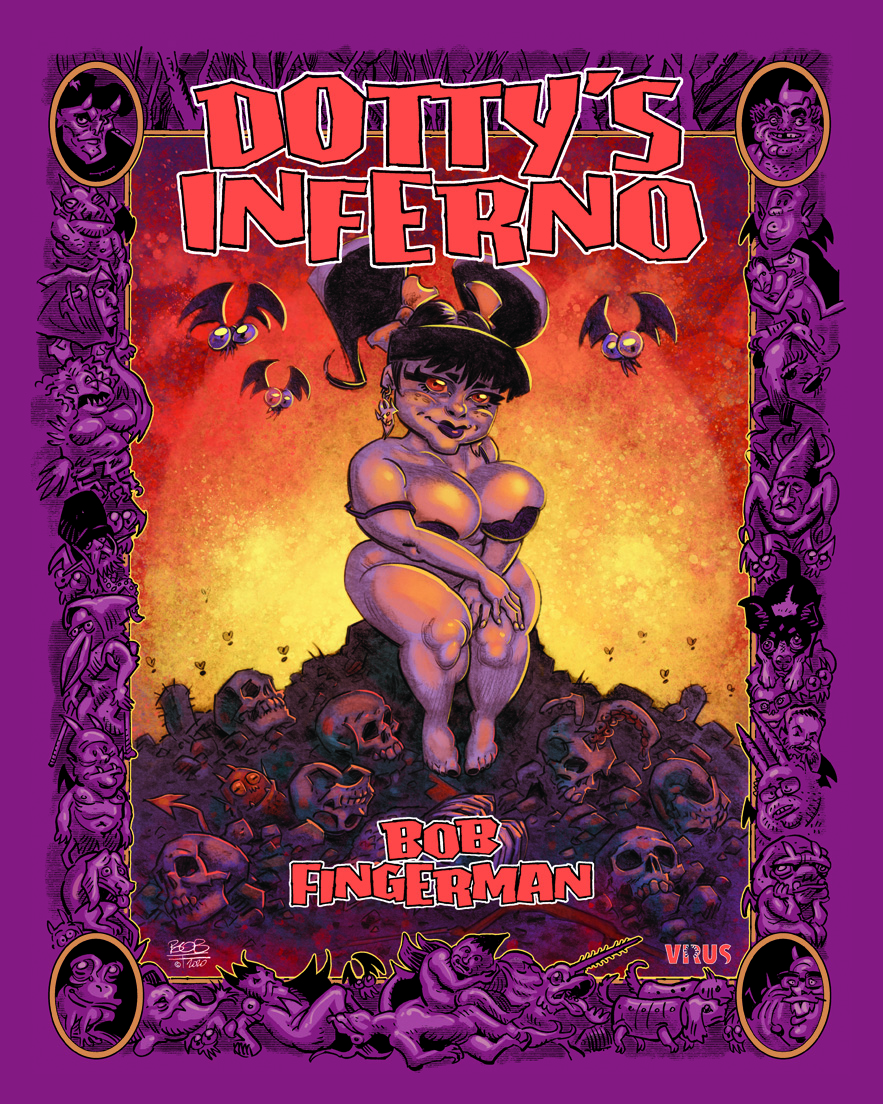

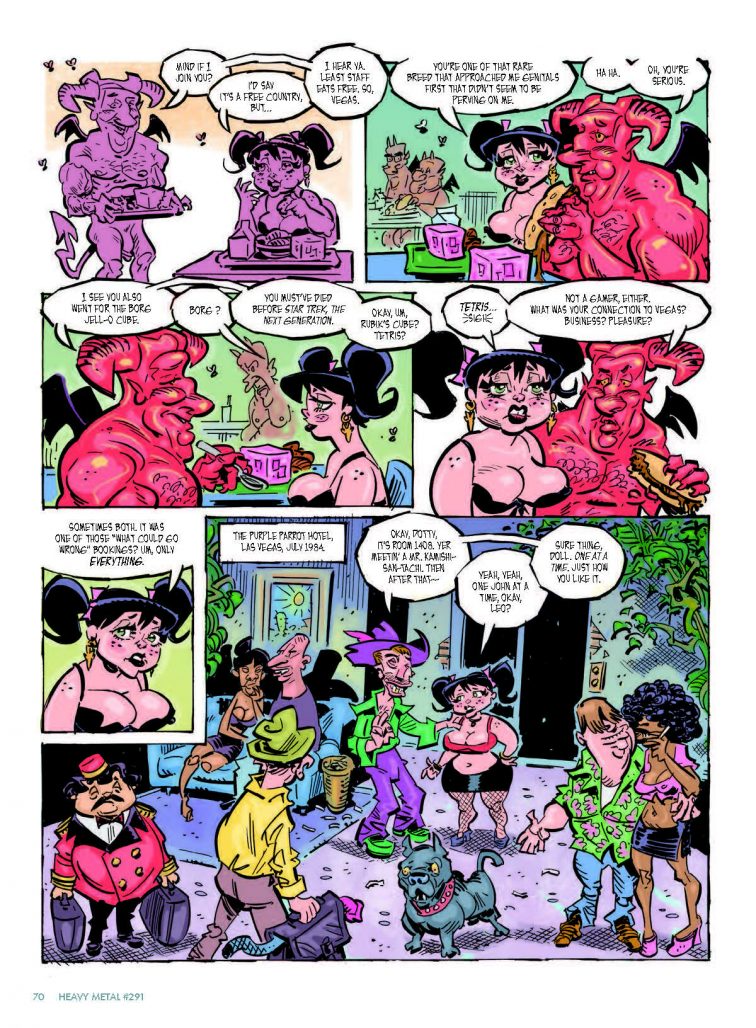

Bob Fingerman has been making quirky comics packed with humor and heart for over three decades. He’s perhaps best known for his long-running semi-autobiographical series Minimum Wage which debuted in 1995. His latest comic may be more fantastical than that tale of working-class New Yorkers, but it’s similarly funny and empathetic. It’s called Dotty’s Inferno, and it’s about a former sex worker tasked with running Hell’s human resources department.

With a new Dotty’s Inferno collected edition coming October 20th from Heavy Metal’s new Virus imprint, Fingerman joined The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber on Zoom to discuss the origins of the project, the artists who informed his idiosyncratic vision of Hell, and providing laughs in the midst of “the most trying period of our lives.”

Gregory Paul Silber: Dotty’s Inferno is a weird one. I mean that in a good way. It’s very much in what I understand to be the spirit of Heavy Metal, both as a magazine, and even I think what most people think of when they think of the phrase heavy metal in terms of aesthetics. I mean, it literally takes place in Hell!

Bob Fingerman: Yeah!

Silber: Heavy Metal, obviously, is a long running magazine and brand, even dating back to France in the 1970s, and they’ve got this new imprint called Virus. What is it about Dotty’s Inferno that made you want to bring it to Heavy Metal, and Virus specifically?

Fingerman: It’s a collection of short, self-contained but interlinking stories. And a couple of them did run in the magazine. So really, they were always my first choice for doing a collection. And I’m glad it worked out that way. You know, sometimes things actually go according to plan! So those happy moments are the ones you cherish. I mean, Heavy Metal is very much part of my creative DNA, that magazine. This is where I reveal my age, but that magazine debuted at kind of the perfect time for me because I was already drawing all the time. But there are certain ages where when you get exposed to certain material… they really help shape your aesthetic. I had never really embraced American comic books very much because I wasn’t a superhero kid. I liked humor and I liked sci-fi and stuff. So when Heavy Metal debuted, I was in junior high school and the cooler kid had a copy of it. And I said, “what’s that?” Once I saw the contents and saw the level of draftsmanship and that it was comics like I’d never seen before, I said, “that’s my path now. It’s very clear to me.” And then underground comics. Basically I was exposed to probably the two most influential things, which were Heavy Metal and underground comics right around the same time. So when you get a one-two punch of Möebius and Robert Crumb… if you’ve got a certain kind of brain like I do, that says, “OK, now it’s clear to me.”

Silber: Yeah, I’m really glad that you brought up underground comics, actually, because a lot of the marketing material has referenced Mad Magazine, which you mentioned, and this feels very Mad magazine. Particularly Mad from the earliest decades of that magazine. But also it does have this kind of underground feel and you do have this influence from Crumb and that whole underground circle. But even when I’m reading it, it feels dangerous in that way that comics of that era often felt like. You know? It’s about a sex worker in Hell.

Fingerman: Yeah. I mean, this is the thing. It’s actually a very interesting time to be putting out something that’s roots are more in, you know, the 60s and 70s aesthetic than now. I can’t pretend to say that Dotty’s Inferno is a very woke book, but by the same token, I think its heart is in the right place. You know? I don’t think there’s a mean bone in its body. So it’ll be interesting to see what the reception is. I like to think it will be good because I think people could use a laugh now, and the primary goal of it is humor.

Silber: It’s interesting that you bring up the idea of wokeness, as it were, because–and I think this is true of any era, not just right now–telling a story about sex workers can be a minefield. But also from the very first panel, it’s very clear that she’s intelligent, she is competent, she is not this inherently bad person.

Fingerman: No, not at all.

Silber: And in some ways I think that is very progressive, actually.

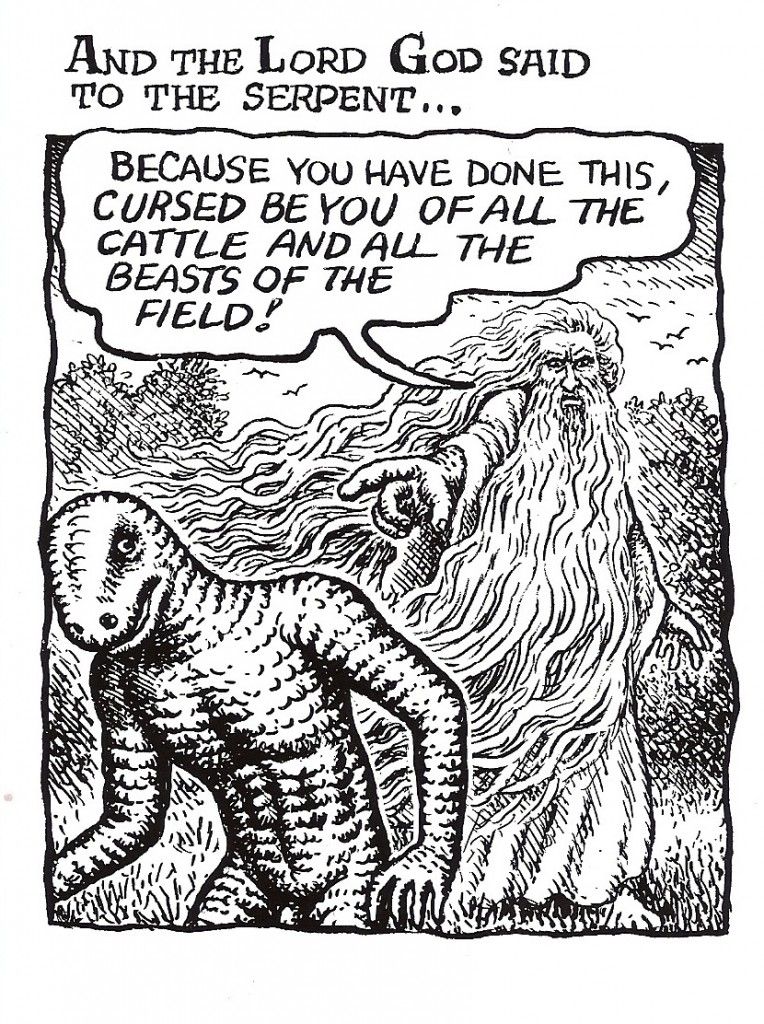

Fingerman: I mean, I hope so. It’s funny, too, because, you know, I’m obviously I’m not the first to depict people nude in hell. I mean, that goes back to Gustave Dorè and other depictions. People don’t tend to be wearing clothes.

Silber: It’s hot down there! Why would you?

Fingerman: Exactly. Well, actually, it’s funny now that you mention that. It seems to me that everyone should be wearing parkas. That would really make it Hell! (Laughs) I never thought of that. Maybe that’s in the sequel. That’s where they really send bad people, you know? Send them to the hottest place wearing snowsuits like Ralph’s kid brother in A Christmas Story. But… America’s roots are the Puritans, and nudity has always been this very thorny thing when it’s depicted… [Bob stops as his dog barks in the background] Hopefully there’s not a home invasion happening as this is going on!

Silber: That would be pretty metal, though.

Fingerman: Yes, yes. Yeah. If watching your interview subject cowering and begging is metal, then I would be your man!

Silber: The idea of nudity being an integral part of the story… I’m glad that you brought that up, because literally from the first panel, it’s just right there in your face. And it’s not even sexual, really.

Fingerman: That’s kind of my point, in a way, that nudity and sex are not the same thing. So, it’s a very equal opportunity book when it comes to that. I haven’t done a genital count, but I’m pretty sure that men actually have the lead in that department. [Laughs]

Silber: What is it about the idea of hell’s H.R. department? I love that juxtaposition. You see images of hell and there are always images of demons stabbing people with pitchforks or whatever, and there is also often this understanding that demons were at one point people who were sent to hell… I mean I’m Jewish, so I actually don’t know how any of this works theologically–

Fingerman: I grew up with no religion at all, so… yeah (laughs).

Silber: But that’s such an interesting idea, that people do have to be sorted into their various hellish responsibilities.

Fingerman: Dante’s Inferno is a good place to start for structuring Hell. I like that structure. I like the whole nine circles. And that all works very well for me. And then you get to play with it the way you want to play with it. But yeah, for one thing, when you meet Dotty and she has just arrived, the guy who’s basically sending her on her way knows she doesn’t belong in hell. But them’s the rules just by virtue of her having been a sex worker in life. Right at the beginning, he just says, “well, that’s not fair, but what can you do?” Her punishment isn’t quite as severe. She’s not getting pitchforks in her for eternity or a lake of fire or anything. She gets office duty. So as far as these things go, it could be worse! Her boss is a demoness who’s pretty, pretty mean. But there again, it could be worse. But I like the idea of, you know, in heaven you get Saint Peter and he’s just ushering you into paradise. But in Hell, you sit down with an H.R. person, and she sends you off to either what’s going to be your torment, or your job for eternity. So that’s that’s Dotty.

Silber: It almost speaks to a certain progressiveness to the way that this in-universe version of hell operates. Because it’s not a punishment-fits-what-you-did-in-life kind of thing. It has nothing to do with the fact that she was a sex worker. It’s just, well, “this is something you’ll probably be good at.”

Fingerman: I had actually written a partial novel that some of this stuff was pulled from… at least the characters. And one of the big reveals–I mean, I still hope I get to write that book someday–but one of the reveals was that heaven has about seven people in it because nobody ever qualifies. And the rules are so specific that it’s just like the most boring cocktail party you’d ever want to go to because everyone’s such a goody two shoes. So really hell is not just where the bad people are. It’s pretty much where everyone is. [Laughs}

Silber: I like that too, because without spoiling it, I’m sure you’re familiar with The Good Place.

Fingerman: Yeah, I’m, I’m about midway through the second season.

Silber: Without spoiling and being as broad as possible, there is the idea that it is so hard to be a good person that the majority of people go to “the bad place.”

Fingerman: It stands to reason, doesn’t it?

Silber: You talk about this mundane vision of Hell, and I think that speaks interestingly to your previous work, stuff like Minimum Wage. When people think of something like that, they think of the slice-of-life idea that you’re now bringing into this operatic setting. Has that previous work informed Dotty’s Inferno in any way?

Fingerman: I’m sure it has. I’ve done a lot of genre stuff, but I think if there was a quality that typifies what I do, in a way, it’s bringing the mundane to the extraordinary. So you know, I’m doing a thing set in Hell, but she works in an office.I did a Hellboy story years ago for when they were doing the Hellboy Weird Tales. The big set piece of that was him battling a vending machine. Take something really over the top and then add something really middle of the road, absolutely quotidian, and smash them together. And I think that’s probably my aesthetic. So, you know, these stories are all set in hell. But one of the stories is her having to go to the pharmacy to get something for her headache. You know? And then crazy shit happens.

Silber: Of course.

Fingerman: Let’s take something that everybody can relate to and then turn it on its ear. That’s how I have fun playing with things.

Silber: It definitely seems that way. That’s an aesthetic I love myself: marrying the mundane with the fantastical. It’s a lot of what I love about comics in general, up to and including a lot of superhero stuff. You brought up your Hellboy story, so that’s a good segue way into some of the people that you have contributing to this book, including Mike Mignola.

Fingerman: Oh yeah.

Silber: You’ve also got Bill Sienkiewicz, and a lot of other names who aren’t the type to contribute art to just any project. So I’m really curious about what your relationship is like with those art pieces.

Fingerman: Well, that’s kind of a carryover from Minimum Wage. I’m trying to remember where the idea first popped in my head, other than I don’t know, I’m sure there’s a certain egotism to it. [Laughs] But really, it’s reaching out to fellow artists and having them do their interpretations of my characters. It’s just something I’ve always found really fun and fascinating. And, you know, I’ve been in the business a long time and have made some really great friendships with amazing, legendary talents. So I thought it would be fun to ask a few friends to contribute a little gallery to the end of the book. And yeah, it is an amazing lineup! So that’s a little nice extra bonus material for the people who buy the book. Mike contributed one, as you said, Bill contributed one. Howard Chaykin, Dan Panosian, and Dave Johnson and John Cebollero. There’s some pretty amazing art.

Silber: You mentioned that this is going to be part of the end of the book. Do you see a possibility for more Dotty’s Inferno in the future?

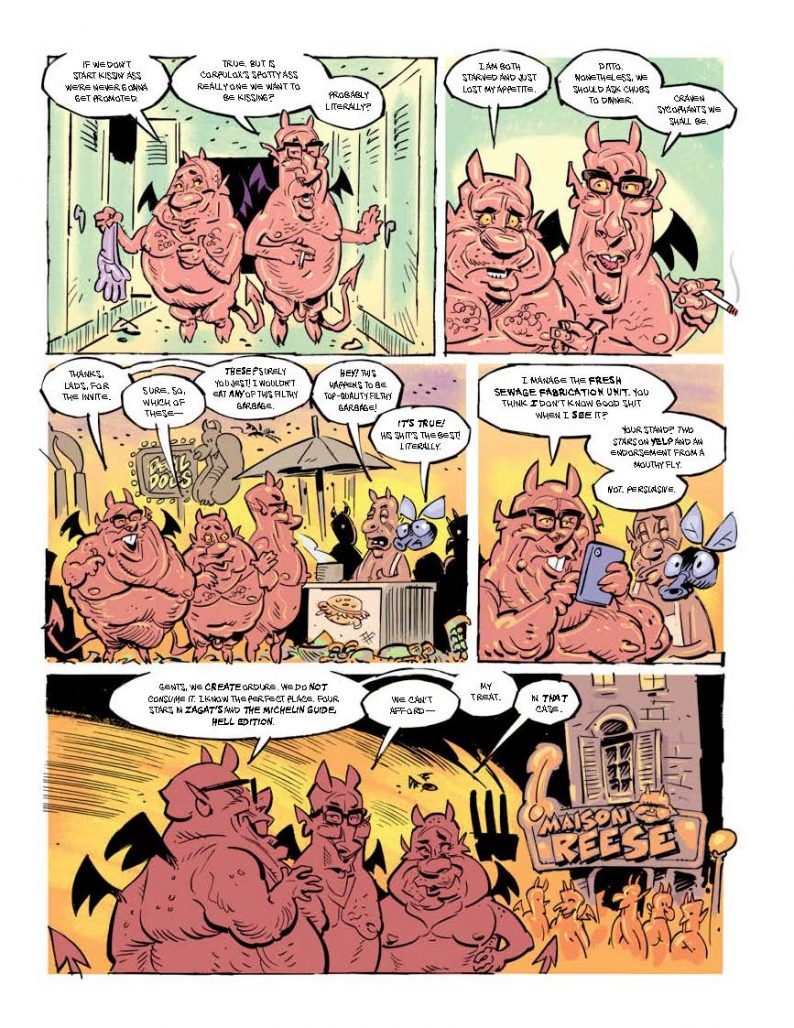

Fingerman: I hope so. I mean, that’s my hope, that this will be the first book of stories featuring her and other characters in hell. There’s a backup feature. Most of the book is Dotty’s Inferno. But then there are also these two demon sewer workers named Ralf and Borax who have a whole chunk of stories in the book as well. So, if I have my druthers, I’ll be doing more books with lots of different characters in Hell.

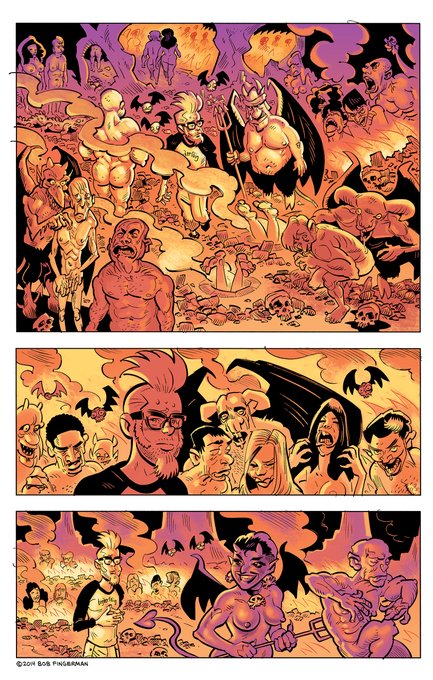

Silber: Another thing I wanted to get into was your art style here. I found the use of color interesting because it’s very striking, even with the demons where they’re not that classic crimson. Some of them are pink! What was the thinking there?

Fingerman: With the exception of one story, they are a very limited color palette. It’s really the range between yellow and purple. So it’s kind of yellows, oranges, reds and purples and a little bit of brown. And that’s about it for the color palette for most of the Dotty stories. The Ralf and Borax stories, actually, each one’s in a slightly different style. So one of them is kind of like the rest of the book. One of them is a more soft pencil, painterly look. And then one of them looks like old comic book pages. So, there’s a variety of approaches in the book, which, again, I think is fun. One of the things I always liked about Dan Clowes‘ Eightball is that he would, you know, have different stories in different styles. And even though it was all him, it was basically an anthology book. That gives you a little more creative latitude.

Silber: You mentioned Dante’s Inferno being an inspiration for the structure of this version of Hell. Did you go back to any classical art depictions of Hell?

Fingerman: Yeah. I mean, I reference visually Doré in one sequence and give him a little a little shout-out. Hieronymus Bosch is all over the book. The little critters, those are sort of my version of George Lucas having nonstop little critters all over the place. You could play “find the Boschling” as I’ve called them.

Silber: Maybe that could be the title here. Bob Fingerman, the George Lucas of Hell? I dunno, I’ll workshop it…

Fingerman: I just hope that people order it and that it gives them some amusement in what is no doubt the most trying period of our lives. [Laughs]. We’re all in this together. So, you know, maybe this is the joke book on the lifeboat…there’s a certain therapeutic quality to doing humor stories, especially as the world kind of gets darker and darker. I think a lot of people have the inclination to just sort of succumb to the darkness. When I was talking with Matt and Kris, I said “Hell is my happy place,” which says a lot about the real world. But at least there I can kind of control the madness.