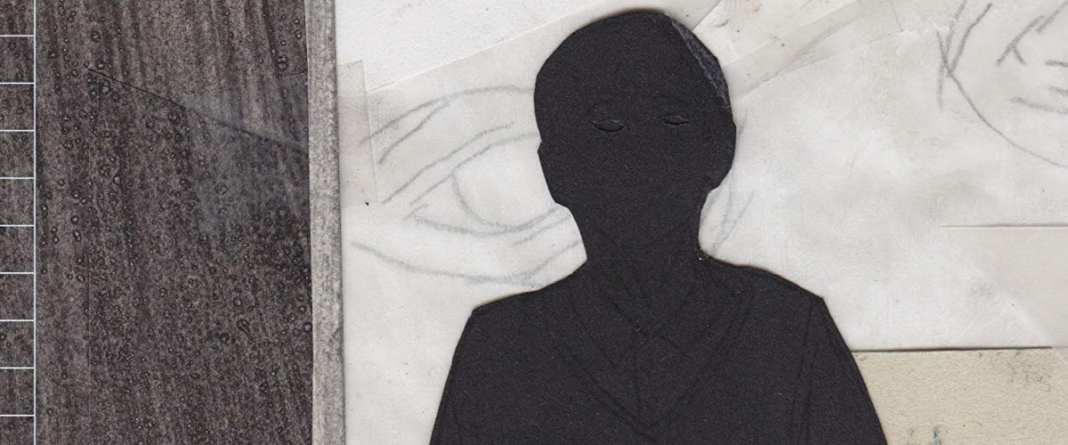

Us Two Together

By Ephameron

Pennsylvania State University Press

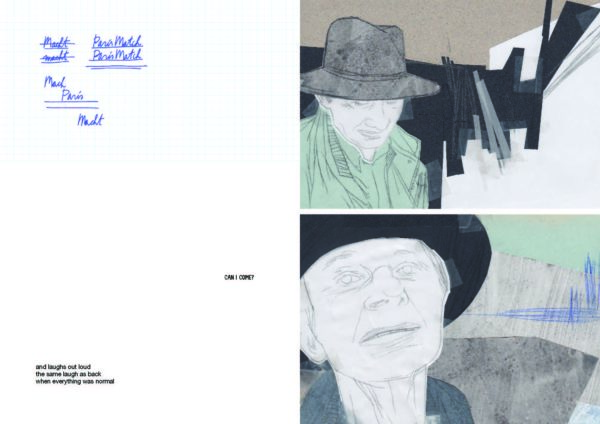

In this delicate, often silent, frequently abstract memoir from the Graphic Medicine imprint, Belgian artist Ephameron documents the painstaking crumbling of her father’s being as he is stricken with dementia.

Ephameron’s father, a university professor, took a summer to step away from his work and just have a break, but he never went back, instead spending the rest of his life battling for a stake in reality against dementia. Receiving his diagnosis at the age of 58, the particular form he struggled with is called primary progressive aphasia, which first robs a person of their language capabilities, a particularly jarring circumstance given his professional relationship with the act of communication.

Primary progressive aphasia begins its work on deteriorating the brain tissue centers for speech and language, but as with other forms of Alzheimer’s Disease, it eventually take the whole person until they just stop. But it’s the time before that last moment that terrifies us, and that weighs down on the families in care of loved ones stricken with it. The person they love is no longer the person they love, but a human shell once occupied by the person they love that will eventually bear little resemblance to that person, a shell that will some day stare right through them as if they aren’t there.

It’s a painful process to document, but Ephameron approaches it with an artist’s understanding that your practice is the way you cope with reality, the way you qualify what you see, hear, feel, think, encounter, and she treats this with the same disipline she would any work. But as she states in the preface, she decided that to keep the story universal, it was best to be cautious about personal anecdotes that would make the book too literal, too specific, and prevent it from inhabiting the emotions of others.

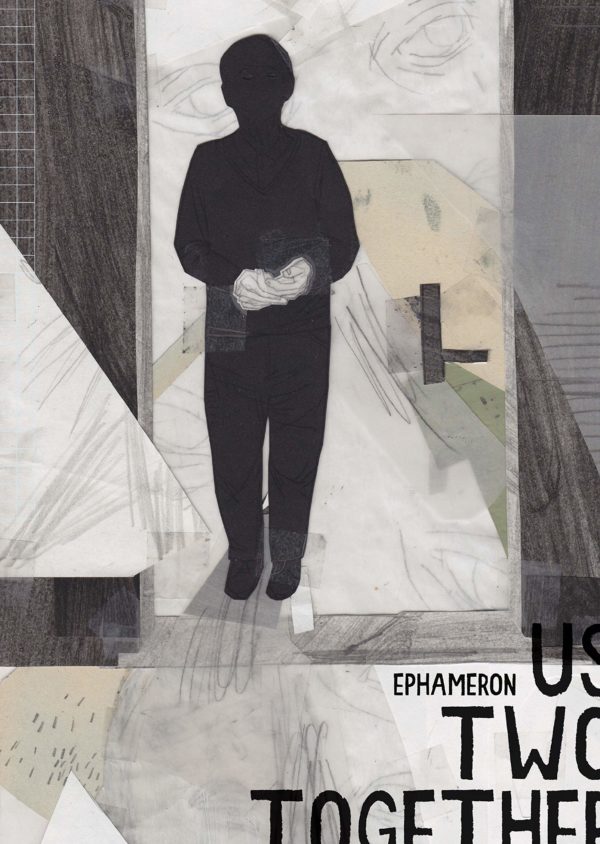

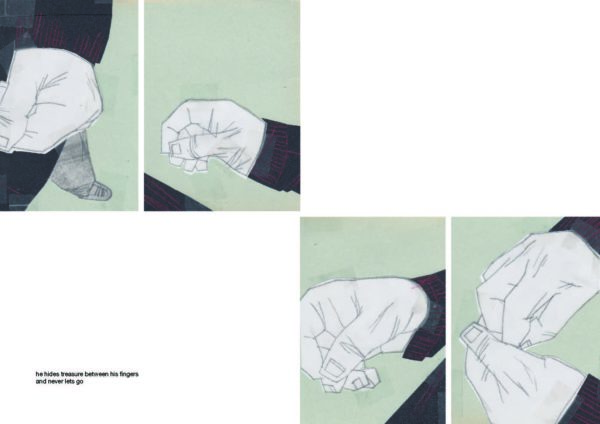

To this effect, she employs, visually, a paper collage technique for the artwork in Us Two Together, which renders the situation as slightly patchwork and not representative of pure reality, which it surely felt like as she was living it. At times, the art shows her father at various stages of his decline. Every so often, it shows Ephameron and other family members. But just as much as any of these, the vantage points of the people are also represented, especially those of her father, which reveal non-descript corners of the house and details of venetian blinds.

She also offers three narrative voices simultaneously. One is lifted from diary entries from her father while he was still aware of what was happening to him. The second is transcribed from things he said when he had degenerated to a point of frequent incoherence. The third is her own. These are straightforward, describing her feelings in the moment. They are not profound, but that’s not what’s needed here — they are honest, spent, and sad. They are often words of grieving that aren’t entirely sure they’re supposed to exist yet, since the condition makes no clear deliniation between when your loved one is with you and when they are gone.

Balancing these conceptual ideas within the design of the book, Ephameron allows for plenty of white space on the pages so that the words are never crowded out by design, and the illustrations are placed in such a way that they balance out the blankness that engulfs the words.

As such, Us Two Together is not story at all, not in the traditional sense, nor is it a memoir as those are typically encountered in graphic novels. Ephameron pulls from her experience as a gallery artist creating installations to craft Us Two Together and use each aspect of the presentation to create a personal encounter with what she portrays for each reader, drawing you in for something that’s hard to put into words, communicating the abstract through a mastery of her craft and an openness of her heart.

Primary progressive aphasia is not a form of Alzheimer’s Disease. It is a variant of frontal-temporal dementia. Although ALZ is the most common and best known, other dementias are just as devastating. Thank you for this article.

Comments are closed.