When Ian Williams started the Graphic Medicine website in 2007 he definitely didn’t conceive of the amounts of other people out there who were either also interested in comics devoted to medical topic or creating those comics. He learned fast though, and as the site began to host conferences in 2010, the online connections he made blossomed into real world ones, far beyond his immediate world in Wales, where he was a physician.

The genre has grown and the conference with it. Over the years it’s featured guests like Scott McCloud, Phoebe Gloeckner, David Small, Lynda Barry, Joyce Brabner, and David B, Whit Taylor, David Macaulay, at locations in England, the United States, and Canada.

And the Graphic Medicine site has expanded also, with a team including cartoonist and nurse M.K. Czerwiec and medical librarians Matthew Noe and Alice Jaggers, and numerous others. In 2015, Williams and Czerwiec collaborated with Susan Merrill Squier, Michael J. Green, Kimberly R. Myers, and Scott T. Smith to create the Graphic Medicine Manifesto for Penn State University Press, which publishes the Graphic Medicine Series.

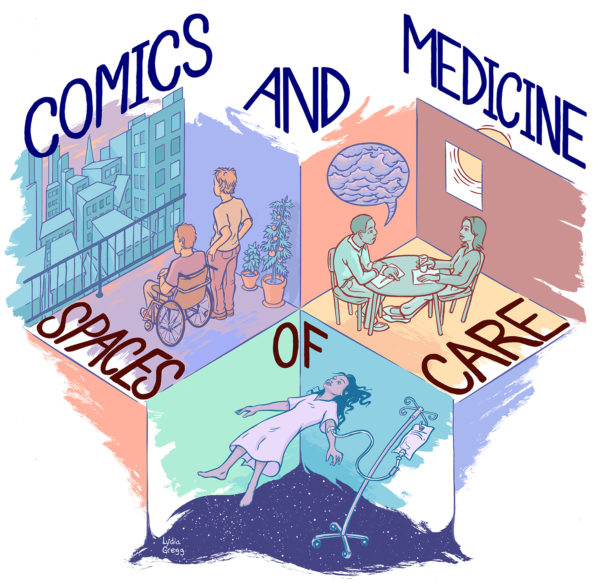

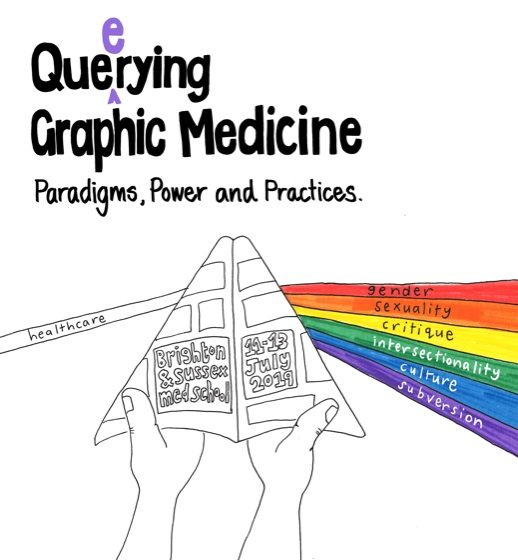

The 2019 edition of the conference in Brighton, England on July 11-13 might be the most successful one yet if proposals are any indication — it receiving 160 from 22 countries, more than ever before. Among the speakers are UK Comics Laureate Hannah Berry and Meg-John Barker, the author of Queer: A Graphic History and the weekend will feature a number of panels, lightning talks, and workshops, many with a focus on queer topics as well as hysterectomies, palliative care, blindness, depression, old age, and other healthcare matters.

———-

Being a doctor and being an artist is an interesting mix, but many people don’t end up bringing them together in their work. How did that happen? Was it always your plan?

I guess the way it was was when I was in school, I was “good at art” and in fact art was the only thing in school that I ever won prizes at. But possibly because my family were teachers and were more into science, I studied sciences at a senior level and decided to study medicine. Partly I thought it would be noble thing to study and partly because of various TV programs, I thought it looked like a good laugh, so it was probably influenced by TV doctors and things like that as well. So I went to study medicine, but I kept up art as a hobby if you like, and then, after qualifying as a doctor, I started doing more and more painting really.

Then I went to art school part time and studied painting and printmaking. And I developed that as a side career if you like, and I exhibited and used to sell work through a gallery in Cardiff and what have you. But then I felt weirdly split between art and medicine and that seemed to be something to do with language, as in when you’re talking about fine art, you use one language and the language of medicine is very different. I decided to do an MA in what’s called Medical Humanities, which is looking at healthcare from the viewpoint of the arts and humanities and social sciences.

And I really loved that. And doing that just completely changed my life and my outlook on everything. Then it was during that that I decided to start writing about medical and healthcare narratives in comics. I mean, it was a fluke really .I was into comics when I was younger and then in the years prior to doing the MA I really got back into reading graphic novels, mostly people like Chris Ware and Daniel Clowes and those American guys. I’d got back into it and then I found Brian Fies‘ book Mom’s Cancer in in the Tate Modern Bookshop in London. and I thought, oh, this is really interesting, a comic book about cancer.

I wondered if there were more out there. So I started looking around and just found more and more comics and graphic novels about healthcare. Some had been already been around for quite while. You know, Harvey Pekar‘s Our Cancer Year. So I wrote a dissertation on healthcare narrative in comics and at the same time I set up the website Graphic Medicine. I almost did that as a procrastination measure actually to avoid having to get down to writing the dissertation. Because I had so much notes of all these graphic novels that I had been reading, I stuck them online and setting up the website really changed things because I thought, oh well, you know, this is fun. I guess a few people will be interested in it but not many. And then people just started getting in touch from around the world.

So I started making some little mini comics and strips about my experiences as a junior doctor and people seemed to like them. I started going to comics. I was really into the hand-bound, like sewing the bindings and stab bindings and making the actual booklets themselves, quite intricate and nice because I was into the book binding elements of it and coming from printmaking, I suppose. So it developed from there. And then I got to know

So it was a really good time to get into it because Twitter was just really starting up. Then the new loads of comics people started going to comics fairs, tabling at comics fairs. Down the line I got picked up by Myriad, the publisher, and they offered me the chance to do like a graphic novel. And so I did The Bad Doctor, which was semi autobiographical. Originally I was going to do straight autobiography about having obsessive compulsive disorder and being a doctor. But I figured it was better to fictionalize it and make the story better so the characters got my experiences, but it’s not exactly me. And that did all right. People liked it and the publisher was really happy and they asked me if I wanted to do another one, so I’ve just done The Lady Doctor, which is the second in a proposed trilogy.

Before you created comics and you were working on gallery art, did you ever touch upon medical topics in your work?

No. It was mostly abstract landscape based stuff because at the time I was living up in north Wales in the mountains. When I was younger, I was really into climbing and mountain biking and that was really why I ended up in north Wales. The painting was all really based on landscape and nothing to do with healthcare. And then I was trying to find a way to maybe combine the two like healthcare and medicine and art, and that’s why I did the MA. So they really helped. I discovered that actually for me where medicine and/or healthcare and art meet is in comics.

And I hadn’t really expected that when I started the MA. I thought I’d be writing about some medical art or arts about the body or whatever. But I found that where my two worlds came together, really was in comics and graphic novels.

And it must have been completely unexpected. At least I can’t say I would have expected to find a community in medical-based comics. That wouldn’t be like the first thing my brain expected to happen.

No, no, not at all. And, and the community has grown because when I first set up the website, I was writing this dissertation and I was looking online for academics that had written about autobiographical comics doing healthcare. I knew were there were a couple, there was Jared Gardner and Susan Squier, but there were hardly any, there wasn’t

So I set up this website and called it Graphic Medicine because I just thought that sounded cool. Suddenly people found the website as a hub if you like and started contacting me. And then it’s like the idea was out there and people had started looking at these things and studying them around the world, but then they started to get together through the website really. And since then the community has grown.

I was communicating with these people and I was still just a rural doctor up in north Wales. I had no academic chops. But I, thought, right, well we should hold a conference. I’m talking to all these people who are professors or writers or professional comics makers, but I proposed this conference and that we hold it in London, so I got a seat at the table. We held the first one in London in 2010 and we thought maybe like 25 people would come to it, but we put a call for papers out and

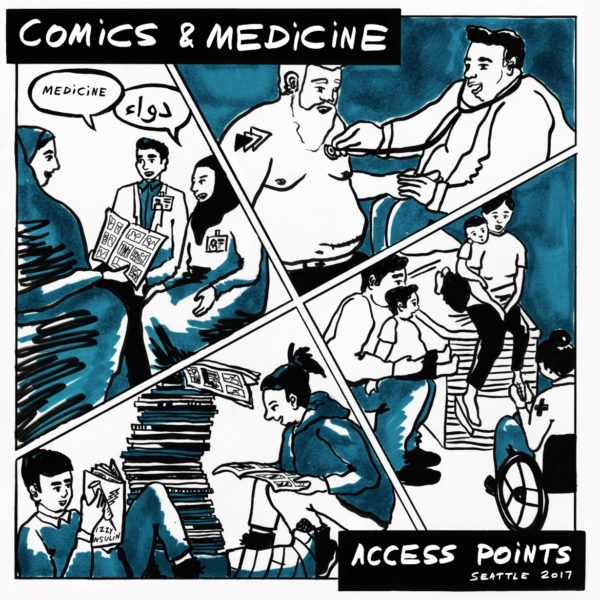

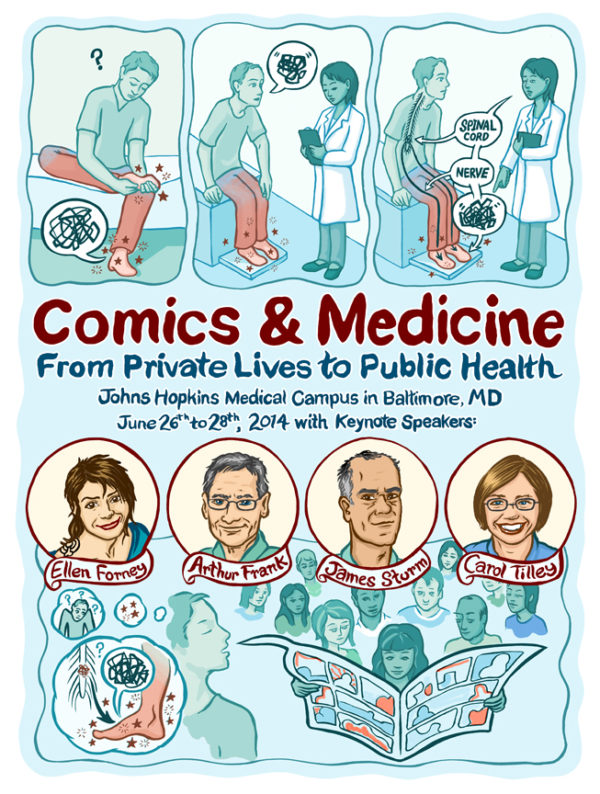

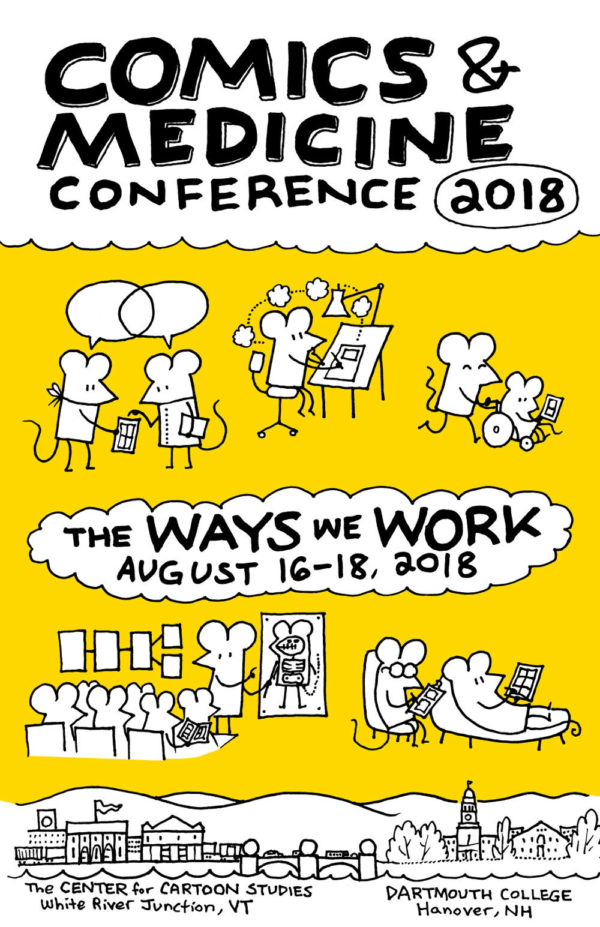

And we were there and everybody was just like, oh my god, this is like really exciting. There’s this big buzz and right at that first conference — I can’t even remember if it was a day. I think it was two days, maybe a one day conference. I can’t quite remember. But M.K. proposed to do a followup in Chicago. And so the next year we had one in Chicago. We had like about 130 people there. And from there we had it in Toronto, then Brighton in 2013 then Baltimore, Dundee, Riverside, California, Seattle, Vermont. And it’s back in Brighton this year

Part of the growth was bringing in collaborators to the Graphic Medicine website. It’s not just you anymore.

There is a big group of us — a steering committee for the conferences, who are the website and the conference series and the conferences and Facebook and things are all part of the same community really. I mean the biggest interactions really go on the Facebook group, the Graphic Medicine group there. So there’s constant interaction there, but everybody that comes to the conferences has become part of the community I guess.

What we found in recent years is that other people are starting to organize conferences with “graphic medicine” in the title or doing their own thing. Last year in Vermont, we had a working group for people who are teaching graphic medicine and there was like 30, 40 people in the room. It was a room for the people who are teaching courses or modules or whatever in their universities — mostly in the states it has to be said. So it’s been really embraced by institutions in the, in the U.S. more so than in the UK I think.

Do you have any sense of why the combination of medical topics and comics work so well together and why people appreciate it so much?

I guess loads of people like comics and you could argue that culture in general is becoming more visual and with comics having become a more respected form of art and literature over the last 20 years, I guess people are starting to look in that direction. And maybe because they’ve read comics when they were younger, it gives them a thrill to rediscover comics. People seem to just get really excited about the idea of using comics in healthcare or using comics as a therapeutic intervention. Maybe they just love the comics themselves or they think it’s cool or whatever.

I mean M.K. and I, and others like Michael Green and Susan Squier, we spent years talking about this to various institutions. And most of the time people in the early days just thought it was a joke or something fairly lighthearted. But as we’ve gained ground and it’s been taken up at an institutional level people have suddenly started to take it seriously. And thank god, graphic medicine has become a thing. Now you get loads of people saying, “oh, this is cool, I’ve just written a paper about something and I’d like to turn it into a comic book,” a lot of, which is really not suitable but people like the idea, they see it as being cool, I suppose. Also at the same time, big institutions like the Wellcome Trust in the UK and big research institutions have used comics in public engagement. So people see that and start to get it.

I’ve probably been doing talks about it for 10 years and I stood in front of rooms of doctors and telling them that they should read comics and they’re just like, what the fuck are you talking about? They just like, who invited this guy here? We want to know about serious cardiological interventions. We don’t want to know about bloody reading comics. But now, well obviously you still will get people responding like that, but you get a lot more people who are really interested and who want to be part of it or want to do something with it.

On the professional side, maybe comics are appealing because it makes the medical field feel less mysterious, more open. On the patient side, it speaks to the common complaint you hear that they aren’t being heard. For them, comics seems like a way to communicate all the things they might feel they are being snubbed about.

Yeah, definitely. And I think it’s just a tremendously powerful, especially autobiographical comics. And my main interest I guess. I just find those like really powerful, like an opening into somebody’s world and you just get this great insight into how people live with conditions. And I mean one of the main value I see, in it is health professionals reading

autobiographical comics to get ideas about people who live with those illnesses or conditions, what their day to day life is like that you don’t get from like a medical textbook. So reading Ellen Forney‘s Marbles is much more valuable. You could read it alongside a textbook of psychiatry if you like, but you’ll get loads of what it’s like, what it feels like, non-propositional knowledge about how the condition affects people’s lives that you wouldn’t get from, from reading a textbook of psychiatry.

I think also things are changing as younger people are coming through who have grown up with a much more visual culture. People who are now healthcare professionals have really grown up reading Manga, reading comics, playing video games, watching Youtube, whereas for my generation, certainly healthcare education was much more text based than it is now. Nowadays people don’t really learn from books as such. Media has changed as well, and that’s probably opening up people’s minds to using different media or different sources of information. Everything has become a bit more democratic. That’s the digital revolution. When I went to university it was before the Internet was really available to everybody. We just learned from books. They had pictures in them, but they were medical diagrams.

The growth shows. This year is the biggest response you’ve ever had from people wanting to attend the conference.

We had, I think, 160 odd proposals from 22 countries. That’s the most we’ve ever had I think. We’ve been having about about 130 and it’s gone up. We were quite surprised because we try and have a rough theme each year and a lot of those themes have focused on trying to bring people who might be marginalized into the community. A few years ago we looked at the conference that we thought it was far too white and there weren’t many people with disabilities there. So we have had a program of trying to bring people, different communities, into the graphic medicine community and this year with the state of the world and Trump and general move to the right, we thought that we would look at gender diversity, queer theory and intersectionality.

We thought that this was apt given, the U.S. president’s general behavior. Well, not just Trump, but all around, like Europe is sliding to the right. Everything felt quite depressing and so we specifically gave the conference a queer theme. A few of the academics thought that’s going to really put off heterosexual and straight white men who might feel excluded or whatever, feel like they haven’t really got anything to say. So we were prepared that we might have a slightly smaller conference, but an interesting one, nevertheless, but then we were completely blown away when we had this massive response. It’s been really encouraging and I think it’s going to be a great conference.

As you look at the expansion of the graphic medicine genre, are there any medical topics that you’d like to see more of? Maybe that you think could benefit from being addressed more in the comics format but hasn’t had much exposure?

There’s a load of comics about cancer and there’s a load comics about mental illness, but people are starting now to do comics about living with other chronic conditions. So diabetes, kidney disease, these are still areas that underrepresented. Things like rheumatic conditions are not terribly well represented — arthritic conditions, rheumatological conditions. There’s quite a lot to do with guts and bowel things.

Areas like learning disabilities are not terribly well-represented. There are comics, but they’re mostly comics about people who are caring for people with learning disabilities. It would be good to see more comics by people with learning disabilities. There’s quite lot to do with neuro diversity, like autism. There’s quite a lot of comics about autism and quite a lot by people who are on the autism spectrum. I mean, there are comics about most things, I think.

From a professional point of view, there are quite a few doctors doing comics now. There are less nurses and allied health professionals. We’ve got a whole panel at the conference about comics and psychotherapy although those are by therapists rather than by people making comics about psychotherapy. It’s like therapists and counselors are taking up idea of using comics or studying comics.

I’d like to see comics from the grassroots workers who don’t usually get a voice. Like, I dunno, hospital porters and those allied health professionals who get the work done in hospitals but don’t usually get the glory or get to speak about it. Operating Department assistants or hospital cleaners, those guys that everything that goes on but don’t really get much of an audience usually, .

Those would be interesting. People in those positions sometimes function like flies on the wall.

They know all the secrets and they know all the gossip about what goes on. But they don’t get a platform to speak about it usually.

From an academic point of view loads and loads of people now are doing educational comics like healthcare education, educational material for patients. I’d really like to see somebody write an overview of that, really study that area because that’s been going on probably since comics were invented, but certainly there’s plenty of public information, public health comics from the 1950s and 60s that are pretty hilarious. And the use of comics in public health messages has been around for years and loads of people make educational comics. But a lot of them you see are not particularly great because they’re made by experts and illustrators, but they’re just giving messages that the doctors want you to hear, and I find a lot of them quite problematic and pretty dull as well.

But there are obviously there are good examples out there and it would be really great to see somebody write an overview, like a book about health education, comics, really study them. There’s very little evidence to say whether they work or not. I mean, there’s anecdotal evidence, people like reading comics to learn about their health, but I don’t think there’ve been many big studies. There’s been very few studies about whether putting health messages in a comic is effective or not. I know a lot of the time the people that want to use comics in that way are making value judgments about the people that they’re making the comics for. You’ll hear things like, “maybe we should make comics about drug safety for drug addicts because people who are addicted to drugs probably read comics rather than read texts or whatever.”

So they’re making assumptions about people’s literacy levels and they’re also making assumptions that people with low literacy read comics, which is fairly judgmental about those people with low literacy and about comics. They’re making a whole load of assumptions that might not be held up if it was actually studied.

It’s as if there’s a need for medical comics packaging agencies that match the medical side with cartoonists, or at least comics-literate people who could consult and advise on projects.

Yeah, and recruiting patients to do the writing as well. Those comics that are written by doctors and made into comics by some slick illustration company should be written by patients with medical input to try and shape the thing in some way. But they’d be more interesting if they were written by people that actually had the conditions rather than being just like told what it’s like. If you’ve got comics about heroin addiction, it’d be much more interesting written by people who are addicted to heroin than written by doctors who are treating people addicted to heroin. So ideally a team of like the people living with the condition and a great comic maker and, healthcare professionals in the mix there as well would be the ideal mix, not just healthcare professionals telling everybody how to experience their illnesses.

I guess that’s one more project for you to organize.

I wish somebody would do it, but I find a lot of educational type comics quite uninteresting because they’re so on message. That’s the thing. They’re putting out the messages that are otherwise put out in textbooks or patient information leaflets and they just try to set it up in a comic form. It sometimes works and there are great examples, but often it just comes over as a bit dull, really. It comes off as dull and often slightly ham fisted trying to make a disease into a superhero or a disease into a super villain or something.

Comments are closed.