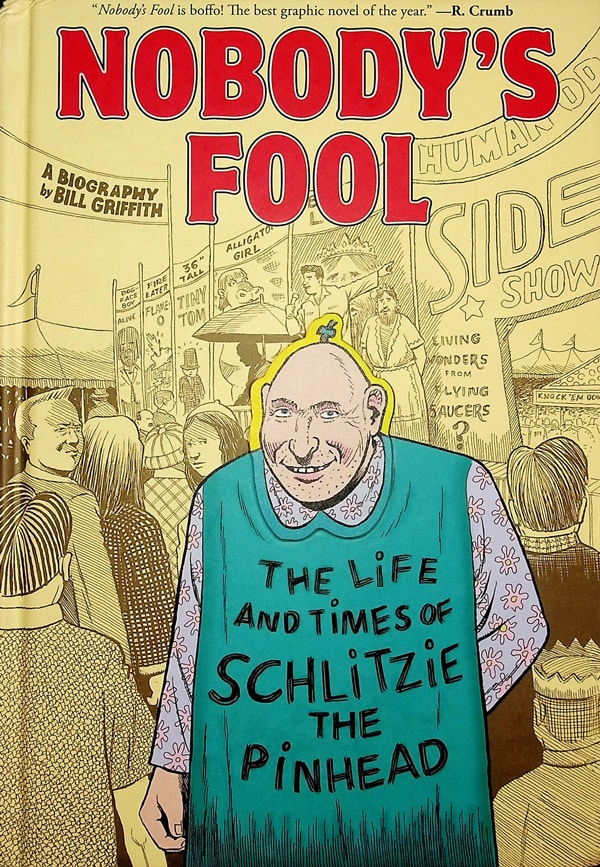

Nobody’s Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead

By Bill Griffith

Abrams ComicsArts

As awful as it can still be, there are some indisputable ways that the world is much kinder than it was when I was a kid. As some people age, they cling to that myth of former innocence, how it was lost at some point. The time of innocence usually stretches from their childhood to somewhere over age 50, regardless of the specific era.

But innocence is just a nice way of saying that certain things used to be hidden and rarely considered, and now that has changed. It’s not just that whatever ugliness was rendered invisible, it’s also that it was presented as an aberration to acceptable normality. Normality is what normal people experience and you knew what was normal by what popular media showed you. If you didn’t experience life in that way, you weren’t normal. And if you weren’t normal, you were ugly. A freak. In the first part of the 20th Century, this circumstance was put into a tangible form in sideshows, where disabled and disfigured humans were branded as different, as ugly, fetishized, exoticized and displayed to “normal people” for shock purposes.

Plenty of people of my age encountered some aspect of these shows at fairs we went to as kids, and they had a strange effect for some of us. One was to create a kind of personal lore that focused on the question, “What exactly did I see?” and wanting an explanation. Another was, for some of us, to create an inexplicable kinship with the people in those shows. Something connected for us, but at so young an age, we couldn’t say exactly what it was. Both led to the same outcome — an adult interest in these shows that led to fascination and study of them.

In 2019, having an interest in the history of sideshows seems as outdated as the sideshows themselves. But there are some things that are too powerful to shake. As a little kid in the early ‘70s in Georgia, I encountered a carnival booth displaying photos of deformed fetuses. I vividly remember seeing one with an elephant trunk formation. Years later it haunted me and I needed to figure out what in the hell I had seen.

That fetus display was my gateway into that world, but the more I read about freak shows, the more I learned to view the objects on display as human beings with lives and feelings and dignity. This opened up my world, helped me grow some empathy, and also provided some helpful perspective about my own struggles.

Bill Griffith’s Nobody’s Fool: The Life and Times of Schlitzie the Pinhead is the zenith of that kind of fascination. The cartoonist built an unlikely career with his character Zippy the Pinhead, utilized as a vehicle for social satire through surrealism. In documenting the life of Schlitzie, Griffith instead dives deeply into harsh reality, but he does so with affection and humor.

Griffith casts Schlitzie as the central figure of his own story, but at the same time, no one else wandering through that story has the script that Schlitzie is working from. Shuttled from show to show, from handler to handler, Schlitzie remains the constant, in some ways transformed by Griffith into a reliable guide to the world of sideshows as his story intersects other fascinating sideshow figures, as well as a few Hollywood ones.

This partly due to the challenge Griffith faces by not really being able to get inside Schlitzie’s head. Schlitzie’s true thoughts and feelings, and the depth to which he thought and felt them are forever a mystery. To the people who knew him, Schlitzie is remembered as good-natured, with a bit of the trickster in him. Griffith obviously likes that aspect since it mirrors Zippy, and he often depicts Schlitzie reacting to things around him with his select array of phrases he was known to repeat. The repetition of these, especially given the moments they are employed, form into some kind of challenge to straight-faced composure of “normal people.” Schlitzie is presented as a figure who cuts through that, whether facing kindness or cruelty, amusement or ridicule.

But Griffith also understands that the sideshow was a realm of multiple untruths piled upon each other. These conspire to obscure any original reality lodged into a performer’s biography and ensure that we can never get to the actual origins, which were often unremarkable in comparison to the tall tales built around their stage personas. Schlitzie, as we remember him, is as much the result of a huckster’s claim as the actual circumstances of his life. We bask in a constant state of unreality in that regard, but Griffith does a commendable job of addressing this issue and uncovering some of what lies underneath.

There’s a rollicking quality to the depiction of the bulk of Schlitzie’s career, but by the 1960s, municipalities were becoming less tolerant of disabled people being put on display. Laws were passed preventing them from appearing, and some claimed it was the government depriving these people from making a living.

There is a certain amount of truth in that. America is an unforgiving society that often refuses to provide for its most vulnerable citizens, and also insists on defining your worth as a human through your labor. America is seldom prepared for nuanced discussions about complicated matters, and discussion of some of the issues here often dissolves into a binary argument fixating on the best case and worst case scenarios and not the reality of the times when the events unfolded.

Schlitzie nearly spent his final years in a grim, almost catatonic existence in the psychiatric ward of the Los Angeles County Hospital, which Griffith depicts with appropriate, piercing distress. Miraculously, he was rescued by an old sword swallower friend. He went back to the sideshows briefly and then lived out his life in an apartment in Los Angeles, taken care of and enjoying his retirement. A better ending for Schlitzie than state care, certainly.

And I can’t help but think of all the other Schlitzies that didn’t live the same life but faced resentment, abuse, and neglect, often locked away and forgotten, whether at home or in some institution. Back then a happy outcome was not the typical one. Go look at any history of the American asylum system and its treatment of the mentally ill. Given that reality, I cannot begrudge even the most cynical of sideshow handlers in ushering Schlitzie into something that was an undeniably better life than most others in his situation. At the same time, from the vantage point of 2019, I can certainly also imagine a better existence than the one he had. And that is one of the points of telling Schlitzie’s story.

Griffith has created a tour de force and provided an honest and dignified, but also playful, tribute to Schlitzie. It asks us to not look back at history and play Monday morning quarterback, but take in the complexities of Schlitizie’s situation and make sure his experience means something now.

Griffith renders the 70 years of Schlitzie’s life with a vivid affection for the areas and landscapes he inhabited, for the cultures he wandered through, and for Schlitzie himself. Maybe it’s just me showing my age, maybe not, but I found Griffith’s book uncommonly touching in representing the experience of someone who was not capable of doing that himself.

You had me in the first paragraph.

Finished now. Great write-up.

Thank you so much, Kaleb!

You’re welcome, it’s very good.

I wasn’t sure if I’d be into this as, “Zippy,” is always well-illustrated but at time really dense and confusing. It sounds like this is a more straightforward story that Griffith tells so I’m excited to give it a read now. Thanks for the stellar write-up!

Comments are closed.