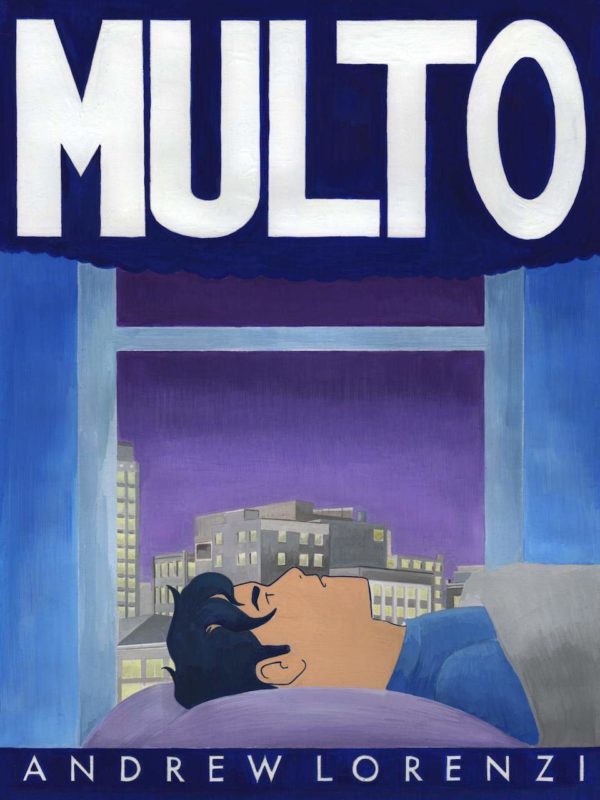

Multo

By Andrew Lorenzi

Retrofit/Big Planet

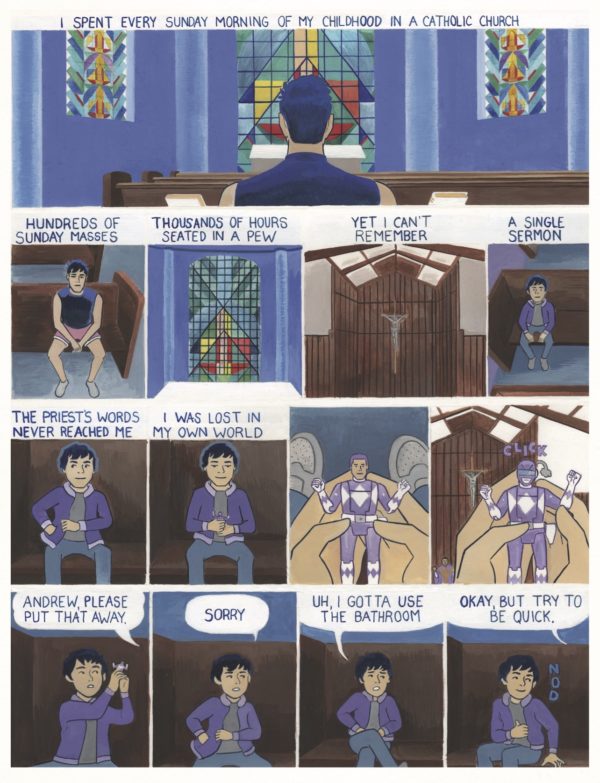

Andrew Lorenzi’s chosen focal point of autobiography to opens his cryptic book Multo is a rumination on his own history with church, spurred on from a post jog rest within one. Sitting in the pews of a Catholic church, Lorenzi recounts his childhood exposure to a Filipino take on Catholicism through his mother that brought fantastical monsters into the mix of religious belief. It was a Catholicism filled with superstition — well, I suppose all Catholicism is filled with that, but this is a form particular to his mother’s birth country and which made the religion a lot more exciting as a kid.

But organized religion within America doesn’t typically encourage those deviations and in some cases actively works to stomp them out, so the official Catholic Church couldn’t capture his imagination the same way his mother could. That seems typical of many religious experiences that I know of, in which the actual religious body can alienate the person even if they hold some of the beliefs close for personal, sometimes nostalgic, reasons that become entwined with their family experience apart from a church-going one. It doesn’t necessarily acknowledge the necessity of personal spirits, only communal ones.

This is the introduction to Lorenzi’s life, followed up with scattered moments that represent very small, very intimate corners alongside more expansive moments in which he looks back and pieces together the aspects that float to the top of his memory. In some ways, Multo is a sensory-focused recollection dominated by Lorenzi’s feelings of a moment, with the sounds and sensations that accompany it. In remembrance of his mother’s work as a nurse, the surface noise of a cassette tape playing in the car sticks in his brain, along with the darkness along the road that he’s previously noted on a page about being awake in the middle of the night.

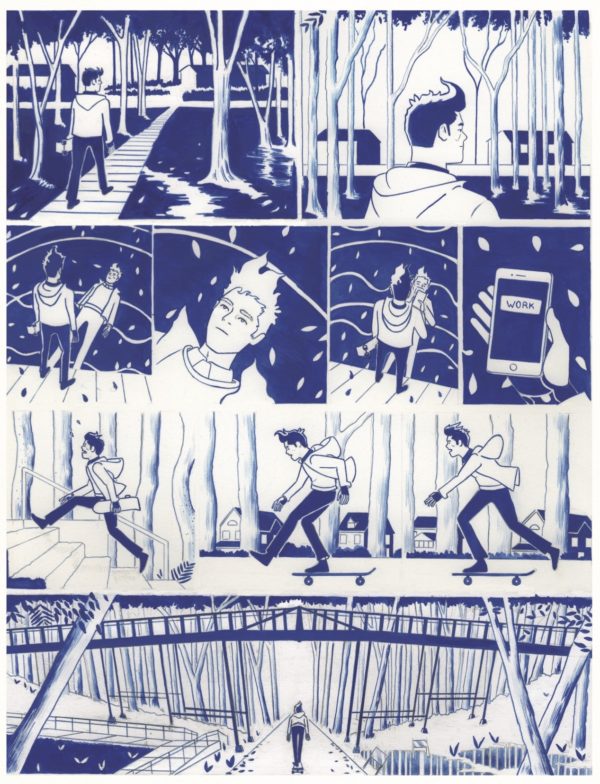

The tactile nature of Lorenzi’s experience is given some context in a brief exploration of his experience with migraines, followed by a description of walking during a snow storm in which the cold becomes a weapon that wounds him, then a moment of silence as he stares into the urban landscape, and finally an extended, silent narrative of his day, a kinetic structure of smaller panels that create a feeling of fast movement with few moments to stop and notice things on a deeper level, though that’s countered with a morning jog and a consideration of how his surroundings have achieved familiarity.

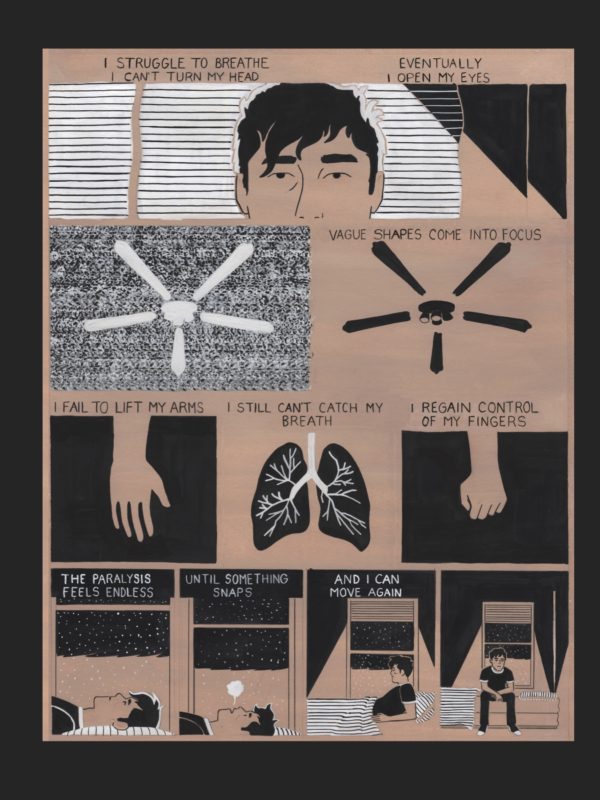

Lorenzi then delves into a detailed history of his struggle with sleep paralysis, which messed with his senses and disarmed his stability, causing him to work towards a place where in order to solve the disruption and panic that accompanies him at night, he has to learn to tame it and shift it to an advantage. It’s an intriguing section of Multo that ends up detailing less a sleep disorder and more an approach to reality itself through a level of meditative self-control that is achieved through night time adversity.

The book ends with some brief respites skateboarding and again walking in the cold, but the impressions left by the sleep paralysis section wind their way through these moments and then back through what we’ve already gone through.

As explained on the back cover of the book, the title Multo comes from the Tagalog language of the Philippines and it means “ghost.” That’s an apt description of Lorenzi’s own presence in the book. Not his visual presence in the stories, but the authorial one, which is the self-aware narrator who steers the wider meaning of the sections through description and also Lorenzi’s art, which takes on characteristics depending on what’s being addressed. Sometimes it’s full and vivid color with clean lines, other times more sketchy, and sometimes overtaken by line-drawings of different colors are jarring in contrast but rich in the completeness it builds through the book.

In the section about sleep paralysis, Lorenzi’s takes on a surrealist aspect that brings the “ghost” into the narrative as an actual presence, smothered in darkness but also giving an impression that it could just well be Lorenzi himself, or at least the emotions that have lurked within him bursting out at night and burdening him with their weight. It’s as if letting them out in a more benign way through comics is further part of the solution that started with his meditative one.

As autobiographical comics go, I really appreciate the mystery that Lorenzi adds to the representation of himself and his life. He doesn’t lay it all out there in terms of giving too much information, but he does emotionally, and while Multo benefits from that honesty, it also asks that the reader do some of the work in taking what’s being offered in order to complete the picture being rendered here. It cuts through the surface of who he is in a way that understands we aren’t cut and dry and easily read, and it’s that approach to personal human matters that has me anxious for Lorenzi’s next work.