Cassette tapes are one of those things. I don’t know if people who didn’t live decades of their life with cassette tapes as part of them can really gather what they mean to people over 40. I don’t even know an equivalent for those in their 20s now. They were physical media that you could adorn with your personal taste.

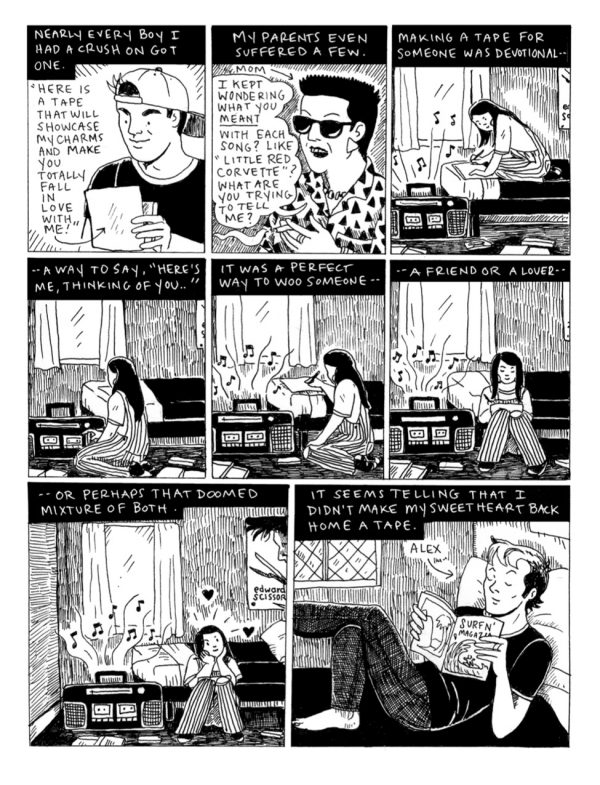

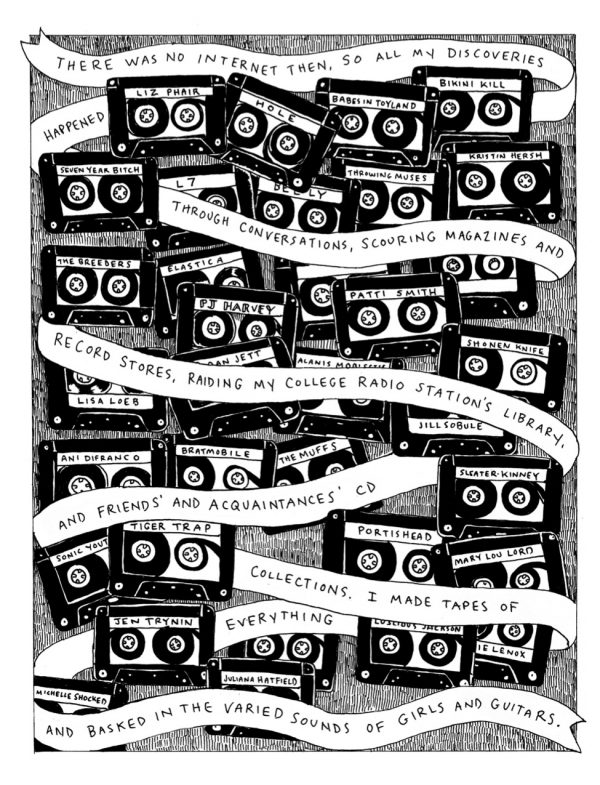

I know CDRs eventually came around, but for a long, long time, cassettes were the only medium available to the average person — or more to the point average kid — onto which you could record. And pass around. So a mix tape held a dual purpose. It was an expression of yourself that you gave to someone else. Or if you made if for yourself, it was a record of who you were at the time you made it. And since it took effort to make them, it was more than just handing over music, it was an activity. The labor involved in making one made it seem a bit like a craft. Making mix tapes and collecting mix tapes could literally be one of your hobbies. It was mine.

Summer Pierre gets all that and she pretty directly says so in her upcoming book All The Sad Songs, a memoir of her relationship to music via her mix tapes and her emotional and psychological journey in regard to all that. I’m guessing that Pierre is about a decade younger than me, but that’s another aspect about making mix tapes that was so nice. It was an activity that people of many ages took part in. I cant share a Spotify playlist with my mother-in-law, but I used to make her mix tapes and she used to listen. Technology, in this way, has separated us. But that’s an old lament for another time.

In Pierre’s telling, mixed tapes function a bit like diaries. After she lumbers down to her basement to pull them out, among the other clutter she can’t yet let go of, she pulls out not a cache of old music, but memory prompts that unleashes a narrative about finding herself as she hit adulthood, figuring out her identity and working for goals that were directly based in the music that she loved and that she lovingly set down on her mix tapes.

The most telling mix tape, for Pierre turns out to be the one that isn’t there, the one an old boyfriend gave her that she tossed away. It may be in a landfill somewhere, but it also left an empty space in her own life that sends her careening through the events that it was part of, and the aftermath of that period.

That cassette is a perfect metaphor for loss, and its loss that really defines your dark side throughout life. It’s not what you have and keep and cherish that grabs your emotional focus, it’s what you had and no longer have, or what you never had in the first place but needed.

For Pierre, that missing cassette is a catalyst for much of what unfolds in this memoir, which largely focuses on her days in the Cambridge/Somerville folk scene in Massachusetts about 20 years ago, finding herself as a musician, but also being forced to look at herself as a human being and working on the inevitable problems that crop up from being one.

At the center of Pierre’s longing is the desire to be loved, to not be alone, to feel a kind of togetherness with a human being that replicates how music can engulf her being and make her feel part of something larger. It’s a brutally honest work and Pierre’s recollections of therapy make me feel that this work is almost like the final component in accepting that portion of her life, a meticulous revisiting of the circumstances and conclusions and what they mean.

Thankfully, Pierre doesn’t focus on the nuts and bolts of her younger struggles and turn it into another slacker autobio comic, but instead presents the emotional journey within the context of her creative one, and that makes it both singular and universal. Not all of us have moved through a folk music scene, and I found aspects of that fascinating, since I just like to hear about other ways of living. But her inner quest for herself is more universal and the years between Pierre the cartoonist and Pierre the young singer-songwriter is time enough to provide the kind of accompanying concepts that place her struggles into more meaningful terms. She’s not in the middle of it anymore, and that perspective gives it all the more meaning in its telling.

Pierre has a friendly cartooning style and an amiable voice, and that helps too. I appreciate using the cassettes as her guides, using music as the legend to the map she builds and combining that with comics as not only an expression of who she is, but what we all might have in common.

Comments are closed.