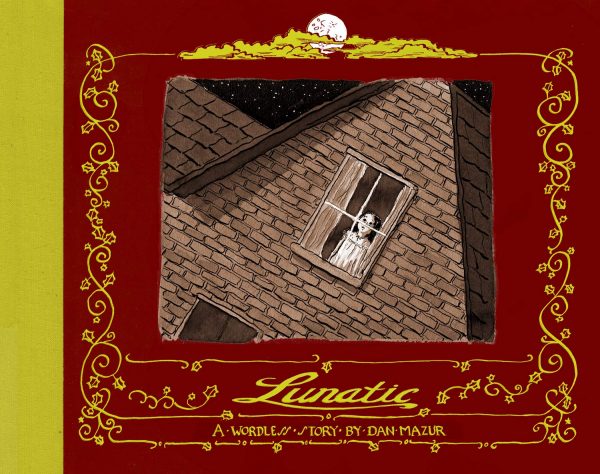

Lunatic

By Dan Mazur

Ninth Art Press

When humans try to understand the non-human world, we have a tendency to anthropomorphize those things different than us. In the case of animals, it’s an act of interpretation that helps maintain a crucial form of empathy that may not entirely be accurate but probably has aspects that align in some way with their inner life. Leastwise it’s a helpful way to maintain cross-species connections that help preserve the lives of animal earthlings.

When applied to theoretical existences, though, it becomes harder to proclaim good or bad, harmful or helpful, whether in religion or science. Speculative anthropomorphism is especially prevalent in our popular culture in our depictions of aliens from outer space. For every triffid, there’s surely a Spock.

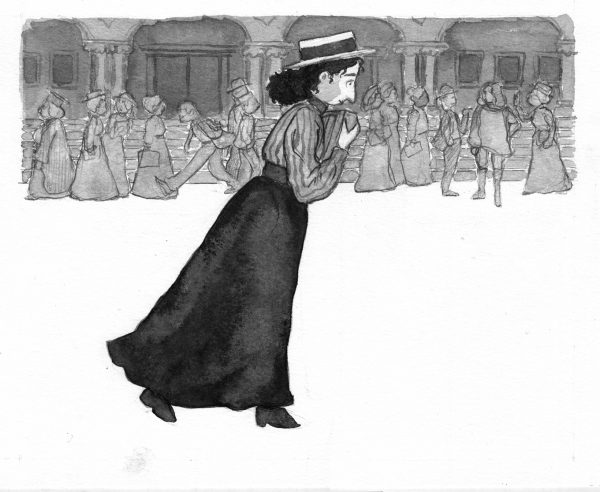

Dan Mazur’s wordless graphic novel Lunatic takes this way of looking to the stars as its starting point, depicting the life of a young woman who looks to the moon for guidance and support. Probably taking place in the 19th Century, the woman’s life unfolds with one important constant — she doesn’t quite fit in with other humans. Not because she’s weird, certainly not by our standards, but because she looks beyond the world she lives in. Her vision and interest are expansive.

In story terms, this means she looks at the moon a lot, and the moon looks back. It starts in infancy — it’s a signal of what makes her different — and continues throughout her life as she begins to reject the norms laid out for women of her time, often with trepidation but always with a look toward the one being that seems to understand her, the moon, for some moral support.

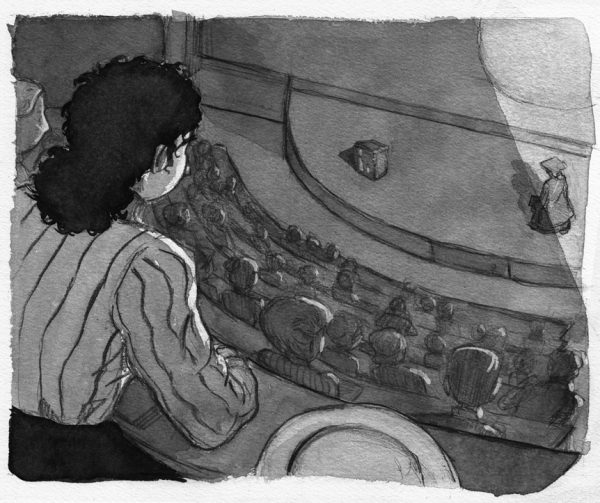

Obviously, such an important figure in her life is not going to satisfactorily remain on the edges of her planet’s rotations and so the young woman truly breaks with societal expectations and studies science, with an eye toward … well, I think you know, I don’t have to tell you.

Mazur tells this story in charming black and white, sometimes stark and other times in stark contrasts with solid black lines demanding attention, though this shifts with some softer pencil sections and lush gray washes that combine into myriad emotions. These styles do the important job of reflecting what’s inside the heart and soul of the young woman in each of her stages, crucial given the lack of words. At the end of Lunatic, Mazur provides an informative section showing how he developed the illustrations for the book in technical and also research terms that documents the processes behind their multi-faceted intentions.

Lunatic is less a drama than a fable, and while it’s easy to place within the “follow your dreams” camp, I think it’s more complicated than that. Lunatic also wraps itself around lessons like “take chances” and “work hard” and “embrace difference” and “don’t let others tell you what to do” and “reach for the unknown.” That last one is pretty important actually, and in Mazur’s telling, science is shown as a way to face the unknown, to train your brain to not allow expectations to be the guiding principles in your explorations, in refusing to allow what you imagine will be to sideline the wonders of what turns out to be.

As such, these are perfect concepts to pass along to those who would enjoy Lunatic the most. While the press material for the book recommends it for teens and adults, I don’t see anything in here that’s unsuitable for anyone younger than that, and in fact, I think this would speak to grade school and middle-grade kids very strongly. What fantastical elements do appear don’t dominate Lunatic, rather it’s all distilled into very personable terms that probably identifiable to a lot of young readers trying to find their place in the world. Lunatic is a good primer in how to view what’s outside of you and how to connect with it on your own terms, but also with an open mind to whatever might dash your expectations.