The Weekend Casserole Collection by Kelly Froh

Froh brings together a number of short pieces from various sources — anthologies she’s contributed to, some of her own minis, as well as some previously unseen work.

Covering incidents from all parts of her life — childhood sleepovers, high school crushes, strangers on buses, work acquaintances — Froh creates a tapestry that might seem scattered at first, but eventually reveals itself as focusing on the idea of Froh the Observer. Though Froh certainly spends some time on herself, these can feel like interludes that allow you to get to know the observer better.

It’s when Froh documents her interactions with the unfortunately thin-haired Eric or too-cool-to-be-friends Cathy or David, the weird guy who flirts with her boyfriend uncomfortably, that the little interludes mean a lot, all culminating in a creepy little story that brings it all together, about Froh hallucinating a figure in the night and going over the possible reasons why.

There comes a point with so many autobiographical cartoonists that you feel like you’re their therapist. The ones that manage to keep your attention are the ones that can link their personal narrative with some larger truth, taking you out of the therapist role. It’s surprising how many self-aware people turn out to be completely incapable of making that leap.

That’s the thing about Froh — you never feel like her shrink. Her manner is such that the experience of reading her work feels more like having a friendly beer with a good talker who has some funny stories. Amiable and insightful, Froh’s tales are as focused on the people around her, ones she observers, ones she meets, as they are on herself, and often, her importance in her own work is measured by the ways in which she is affected by these other people.

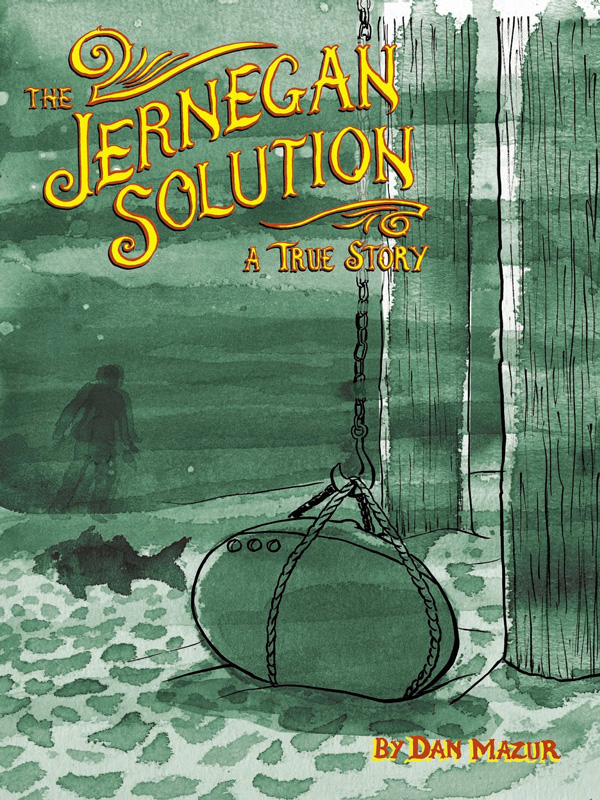

The Jernegan Solution by Dan Mazur

Mazur takes a minor but fascinating incident in New England and uses it to present a meditation on human gullibility, particularly in the face of riches. The small seaside town of Lubec, Maine, becomes the home to the very exciting Klondike Plant under the ownership of the Electrolyte Marine Salts Corporation. Its job? To mine the oceans for gold through a miraculous modern scientific process developed by aloof Baptist minister Prescott Jernegan.

As seen mostly through the eyes of the local Lubec newspaperman covering the story, Mazur is able to cover a lot of ground in not a lot of pages considering the girth of the true story. Mazur does a great job of capturing the wider impact of the factory, specifically its effect on the citizens of Lubec and their relationship with the outside, more modern, world. He transforms this into an examination of how hope can possess a community and blind it to absurdities, packed with a lot of research that is expressed through the narrative in a clear, orderly, and definitely uncluttered way that allows for the emotional content to define the storytelling.