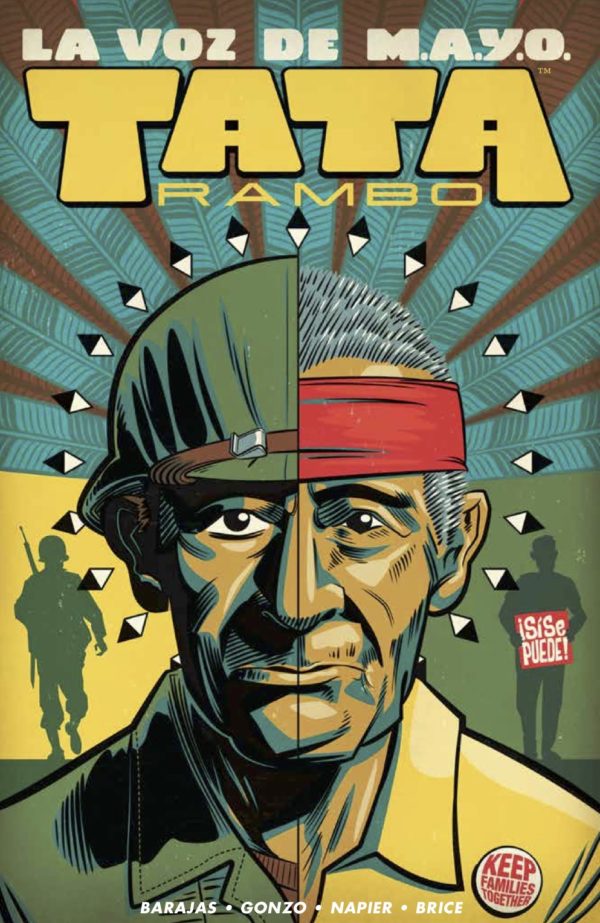

La Voz de M.A.Y.O: Tata Rambo

Written by Henry Barajas

Illustrated by J. Gonzo

Image Comics/Top Cow Productions

Originally a self-published mini-series, the result of a successful Kickstarter campaign, La Voz de M.A.Y.O: Tata Rambo does the important work that so much mainstream history never has. The past is filled with crusaders who have worked for the betterment of the lives of marginalized communities, but their names mostly stay amongst the population they affected positively, since these are areas of the country that typically do not steer the journalistic or academic laudations that create renowned heroes in our society because they do have voices loud enough or, quite honestly, the deep pockets that are too often required to sustain immortality in American society.

Author Henry Barajas needed to look no further than his own great-grandfather to find a person whose efforts deserved to be brought into the wider scope. Ramon Jaurigue was the co-founder of an advocacy and activist group called M.A.Y.O. — Mexican, American, Yaqui, and Others — that was based in Tucson, Arizona starting in the 1960s and achieved important victories but, much to Barajas’ astonishment, seems to have been lost to time. La Voz de M.A.Y.O: Tata Rambo is his attempt to both correct that and to simply tell an important story about the Latinx and Indigenous communities and what was achieved politically in Arizona.

Barajas recalls that he was often told by other family members what a great man his great-grandfather was, but feeling that their proclamations were lacking in actual information about his accomplishments. Realizing Jaurigue was at the end of his life, Barajas decided to pull from his own background as a journalist to document the story of his great-grandfather, who didn’t live to see the graphic novel that resulted from interviews with his great-grandson and the accompanying research involved.

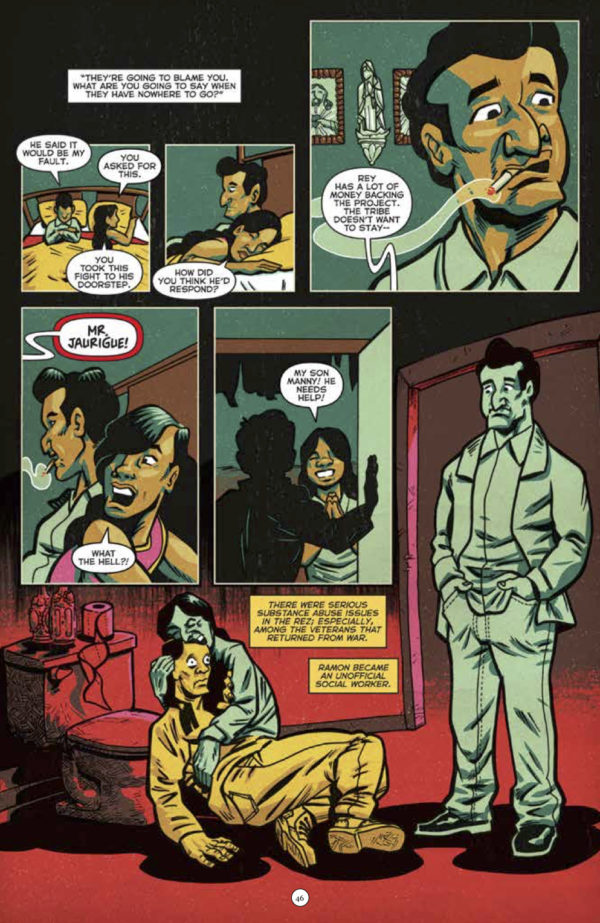

A World War II vet who dealt with recurring nightmares about his service, Jaurigue lived on the Yanqui Reservation just outside of Tucson, Arizona, where he was married with three children. The Yaqui are indigenous to Mexico, and Jaurigue belonged specifically to the Pascua Yaqui, who entered the United States during the Mexican Revolution in order to take refuge in ancestral lands located there. It was in 1969 that his local advocacy on the reservation took him beyond its borders when the land was threatened by a local developer who wanted to relocate the tribe in order to build a freeway there.

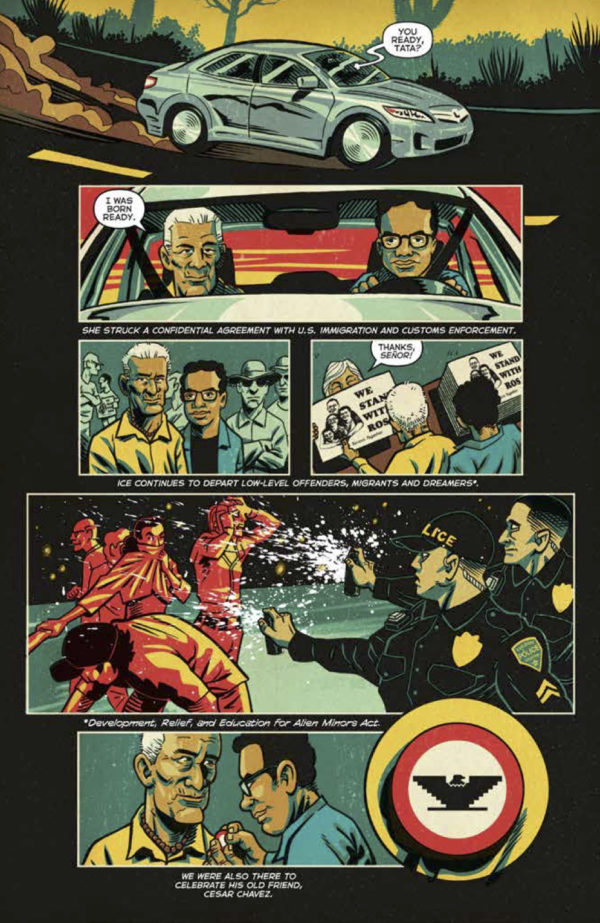

The story Barajas tells follows Jaurigue as he works to mobilize M.A.Y.O. to protest the freeway while he works behind the scenes to fight the construction with Arizona Congressman Morris K. Udall, who had in 1964 helped the tribe take control of their land, and National Farm Workers Association cofounders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta.

But the story also covers aspects of Jaurigue’s personal life and reveals a man who strayed from his marriage when temptation arose alongside his activist power and often sacrificed his relationships with his children in order to devote his time to the greater good. Barajas doesn’t attempt to apologize for his great-grandfather’s failings or lionize him in any manner, but rather to present a political account of a major incident in the history of the Yaqui people in Arizona with an honest examination of the man who was so important to the effort, but also a strong acknowledgment of the others involved who were crucial to its success.

The story is also an opportunity for Barajas to look at himself and other members of his family, most notably his great-grandmother, Leonor Jaurigue, the subject of a touching epilogue. Barajas adds some historical extras at the end of the book, including reproductions of the M.A.Y.O. newsletters that his great-grandfather created, newspaper clippings about events described in the comic, and a five-page typed document by his great-grandfather.

It’s also important to note J. Gonzo’s role in not only bringing this story to life visually but doing so with a style that gives it imbues it with a unique flavor matches the personality of Jaurigue — energetic and colorful. Gonzo, a self-described Chicano artist who lives in Arizona, describes his artistic aesthetic this way on his website: “My formative years were shaped by the rigid tradition and Byzantine iconography of the Catholic school I attended juxtaposed with the DIY aesthetic of the late 70s, Orange County Punk counterculture peppered with the bright, bold, Hispanic hues of my grandparents generation.” I quote that because he puts it a lot better than I ever could, capturing well what’s so unique about his art-style and why it’s inseparable from the story that Barajas laid out — it’s the perfect union to reveal this moment in Latinx history, born to be together on the page.