Latinx Comics is having its own March moment.

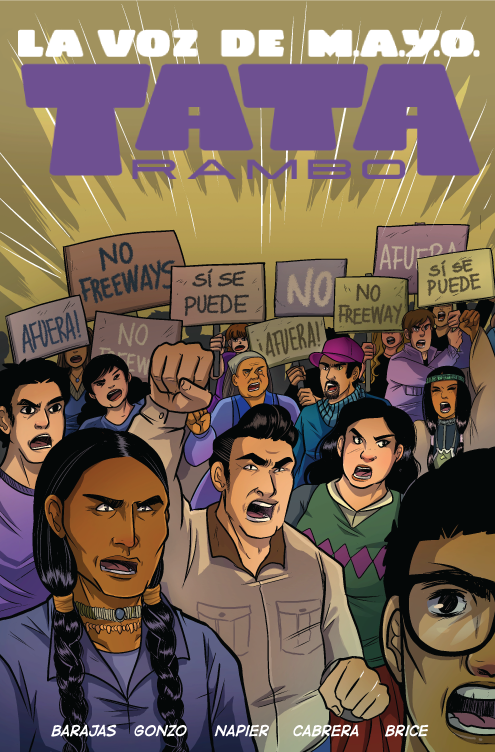

Comics Beat alum Henry Barajas and Jason “Gonzo” González’s La Voz de M.A.Y.O. Tata Rambo #1 is bringing memories of Latinx activism forward by confronting readers with a story that has not been given the time it deserves in the public arena. The comic forgoes the “did you know” aspect of storytelling we’ve come to expect from other journalistic or historical comics in a favor of developing a different kind of dialogue. What information we get feels like a condemnation of how Latinx history has been pushed out of the larger national narrative. Needless to say, La Voz de M.A.Y.O. is a necessary comic.

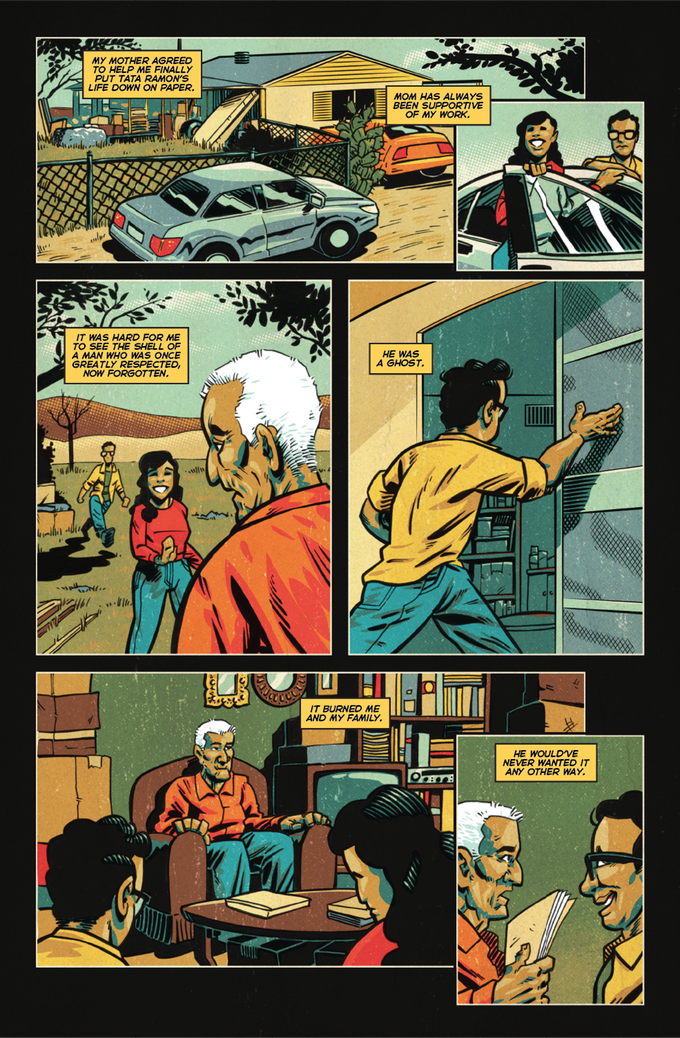

Issue #2 of the series has hit Kickstarter and is already off to an impressive start (which already looks to be a repeat of the first issue’s funding success). For those who haven’t read the first issue–and you should–La Voz de M.A.Y.O. offers a raw and hard-hitting look at Latinx activism in Tucson through the life of Ramón Jaurigue (Barajas’ great-grandfather, also known as Tata Rambo), who resisted the city’s plans to remove Latinx families from their homes to develop a freeway that cut through Yaqui territory. Jaurigue led the Mexican American Yaqui and Others (MAYO) organization in a fight to secure rights, protection, and recognition from both Tucson and the national government.

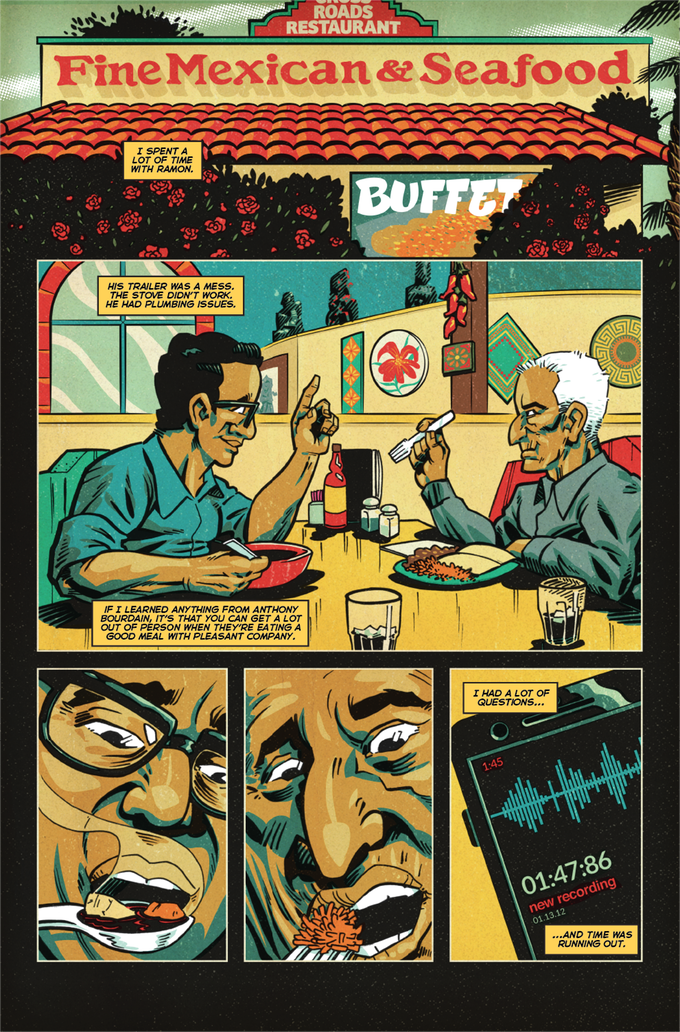

The book reads like an investigative report on Jaurigue and the MAYO movement, intimate in its portrayal but epic in scope. Gonzo’s art is vibrant and urgent, as if the protests themselves were playing out before you, making it your duty to witness and participate. It complements the script’s journalistic voice quite well.

I had a chance to interview Barajas and Gonzo on the comic’s inception, the research process, and how Latinx representation translates into the comics page. Comic pages featured here are from La Voz de M.A.Y.O. #2.

Ricardo Serrano: Can you comment on how both of you got to developing this particular story and what the vision behind it is?

Henry Barajas: My comic is a story that has been passed down orally my whole life. I decided to write about my family history when I became a freelance journalist after working with The Tucson Weekly. Originally, this was going to be a biography about my Tata Rambo, Ramón Jaurigue. Ramon was a WWII Vet and political activist that lived a colorful life, and I wanted finally put down his story more for myself. After reading John Lewis’ March he co-wrote with Andrew Aydin and art by Nate Powell, I realized that making a comic biography was possible. At that point, I self-published comics and had a serious understanding of how Kickstarter works. My boss, Matt Hawkins, told me I should work with J Gonzo. We have gone way back from my days tabling at Phoenix Comic Con. He’s a serious talent and it has been an honor to work with him. My only note for the comic was I want this to look like a Tucson sunset. He’s the mastermind behind the art. He’s like a one-man Alfonso Cuarón.

Gonzo: I have no real part in the inception of the comic- it was Henry’s passion project and I always enjoy working with passionate people. The personal nature of the story drew me to it and servicing this deeply personal tale with respect and authenticity became my paramount concern. The themes and narrative in this comic are grossly underrepresented within mainstream American media, generally; and in comics, specifically, so I did my best to ensure that it was as visually impactful as my skills will allow.

Serrano: You managed to get a lot of evidence, sources, clippings, etc. when researching this story. What was the research process like both for writing and illustrating the comic? Was it easy or hard to access?

Gonzo: I did a lot of online visual reference research to maintain the appropriate look and feel of the variety of eras that this book spans. I want my representation of these real places to have my style, but also be accurate as possible. I hope to not have an anachronistic element pull a reader out of the story; and, with the internet, there’s no excuse to include one.

Serrano: I think you’re spot on with the way Latinxs carry themselves when asked to share their experiences. It speaks to a history of discrimination and oppression, and of being prohibited to belong in other places. How do you approach that both visually and textually? I’d imagine there’s a worry Latinxs only come across as victims in their stories, which shouldn’t always be the case. Your comic is a great example of that.

Barajas: I don’t worry about the victimization because there is a level of oppression that is real and need our undivided attention. The scope of the story is that these people did overcome and are still a thriving nation within an oppressive country. I saw it with my own eyes growing up in Old Pascua, and here’s definitive proof, so here’s the comic book. I made sure to let the characters speak naturally while avoiding the cliche choppy, simplistic dialogue you read and hear the way natives are portrayed in film and television. Only one person has brought it to my attention but there’s a subtle panel where Ramón is pouring liquor in his coffee for breakfast. That was my way of addressing his and native people’s battle with alcoholism. Gonzo picked up on the cues and executed it masterfully.

Gonzo: I completely agree with Henry’s answer. I will add that I always feel that the two main components of comic books (the art and the words) allow Comics to express separate, but compatible sentiments simultaneously; which is perfect for tales of all marginalized peoples. Marginalized peoples spend their collective attention and energies fighting their struggle and express their unique beauties. With La Voz de M.A.Y.O., the text and narrative express and explore the history or the struggle while the art of the comic expresses the beauty of our culture – fighting the struggle affords us rights and equality; expressing our beauty affords us our dignity – Fortunately, comic books allow for both.

Serrano: You mentioned March as an influence for the book. Any other books or movies that also served as influence?

Gonzo: Just spending time in Tucson was a big influence on me; that place has a great feel of history when you’re there, and able to walk the streets that the people in the comic walked, it’s a huge help. Also, this being a biography of sorts, I referenced the two best biographical documentaries I ever saw – one was about Allen Ginsberg from the early 1990s and the other was about a guy who retired and moved to Alaskan wilderness to live. Both these films were made before the Ken Burns-a-fication of documentary film making. They were less flashy affairs; free from heavy hand of editors and special camera effects. They each had long passages of quiet, unnarrated moments that gave greater insight into their respective subjects far better than any dramatic reading of a historic letter. Those were the kind of moments I sought to create in La Voz de M.A.Y.O.

Serrano: What’s next for La Voz de Mayo? Do you have an endgame or will it expand into other Latinx experiences of social struggle?

Barajas: Latinx will always be a component in anything I write because I try to draw from the world around me. It’s inescapable. I can’t wait to tell other lost Tucson stories in the true-crime realm. I’m cookin’ up something that has been haunting me for a while. I’ve also got a desert noir, fantasy story, and whodunit that combines my love for wrestling. I’ve said this many times, but I’d love to work with Gonzo again after this is all set and done.

Gonzo: This being Henry’s family history; the future will be up to him. If there is more story to tell, I’d love to help tell it. I do get explore the ethos of the Latinx struggle allegorically within my own comic and it’s a theme that most likely be present in most of my future work.

Serrano: Thanks for talk, guys!

Barajas: Thank you!

Gonzo: Thanks!

Comments are closed.