My fascination wasn’t just the quality of his films, but his lack of presence in Hollywood. Spielberg, Lucas, Scorsese, Coppola have all been endlessly quoted about this or that for 40 years, but until Scott began his octogenarian victory lap, he was mostly known as a curt, curmudgeonly grumbler. A recent New Yorker profile on the occasion of Napoleon, a two and a half hour biopic on a heroic scale, is the first in-depth look at his life I’ve read, and it’s full of classic utterances about baboons, enemies, and wine (“I thought all the wine should be about health, fun, sex, dogs.”) It becomes evident why he doesn’t dwell on analyzing things.

Scott’s previous lack of introspective insights, despite the fact that he’s one of the greatest directors who ever lived, is because he’s a visual man first. Trained as an artist, a cartoonist on the side, Scott sees the world in its most distilled essence, and puts it on the screen, on time and on budget. (The Battle of Waterloo was shot in a mere five days, according to the New Yorker piece.) He’s an instinctive genius who doesn’t need to spend a lot of time explaining himself.

Scott’s mastery of the visuals is accompanied by an story sense that doesn’t always know when a script is great, but know how to shoot it anyway, a characteristic that directly leads to his uneven oeuvre. Unlike a cerebral over-thinker like Christopher Nolan, Scott approaches storytelling head on – health, fun, sex, dogs – details of set design and costuming revealing character as surely as words. As with Oppenheimer, Napoleon offers immersive experience into a great person’s life – but one you don’t draw many conclusions one.

Napoleon seems to be a subject that Scott was destined to film – his first movie, The Duelists was set in a similar time frame, and bicorne hats seem to have a special place in Scott’s soul. The tumultuous unfurling of history – an entire Napoleonic Era! – offers an overstuffed Christmas stocking of set pieces and characters for an ambitious director. No wonder the director’s cuton Apple TV will be four hours long.

That said, Napoleon won’t win Scott his first ever directing Oscar – it’s too quirky and muddled. It does provide unforgettable visuals and a nearly-accurate accounting of history that has even found its way to TikTok. In short….it’s a Ridley Scott movie through and through.

Screenwriter David Scarpa was tasked with distilling 20 years that shaped the modern world and the principle players into a movie that audiences could sit through without the absolute necessity of a bathroom break. The result is a throwback to historical epics of the past. You know, the kinds of movies that would generally star someone like Charlton Heston – a sturdy vessel with powerful deltoids who masters an acting range from looking noble to “We need to get this done!” to “Oh no, I’m dying!” without the need for much in-between.

With Joaquin Phoenix as Napoleon, we’re far from noble or deltoids. In the fashion of modern protagonists, this Bonaparte is personally awkward, romantically challenged, a whiz on the battlefield and in negotiations but painfully unaware of his own inner workings. Human, in other words. (Scott declined to show the hemorrhoids that some have theorized as a cause of Napoleon’s Waterloo missteps in the theatrical version, but one guesses they’ll be in that four hour director’s cut.)

Phoenix’s picture is in the dictionary next to “Awkward outsiders” but he brings something of the ruthless Commodus in Gladiator to the role and avoids going 100% Arthur Fleck/Freddie Quell, thankfully. This is a Doc Sportello (Inherent Vice) level performance – occasionally bumbling, occasionally brilliant.

As in life, the center of Napoleon’s personal life is his wife, the empress Josephine, played by Vanessa Kelly. It’s a showcase role, another in Scott’s long, long line of women on film who are just as human and motivated as the men, something much rarer than it should be. Josephine is no supportive decoration, but capable of holding her own on the stage of history. Napoleon is obsessed with her as his northstar even when she flagrantly carries on an affair and their spats are played for cringe humor.

This take called for a more Rabelaisian raconteur as opposed to the chilly, elegant tableaux that Scott’s specializes in here – he’s very much channeling his inner Kubrick, who failed in his own attempt at a Napoleon project and settled for Barry Lyndon instead. Many will find this difference in tone uncomfortable. (It’s something he handled much more assuredly in House of Gucci, which was an inherently tawdry tale.)

Although many critics found the Napoleon/Josephine relationship the best part of the film, the cutting between them arguing over a lambchop and the historical, bloody battle scenes is mesmerizing if you have any interest in the outlines of history. And here Scott truly shines, from an eerie battle on a frozen lake of Austerlitz to the burning of Moscow to the classic blunders of Waterloo. A sneering Rupert Everett as the triumphant Duke of Wellington suggests why French critics found the movie unappealing – it’s pretty clear which side Brit Scott is on.

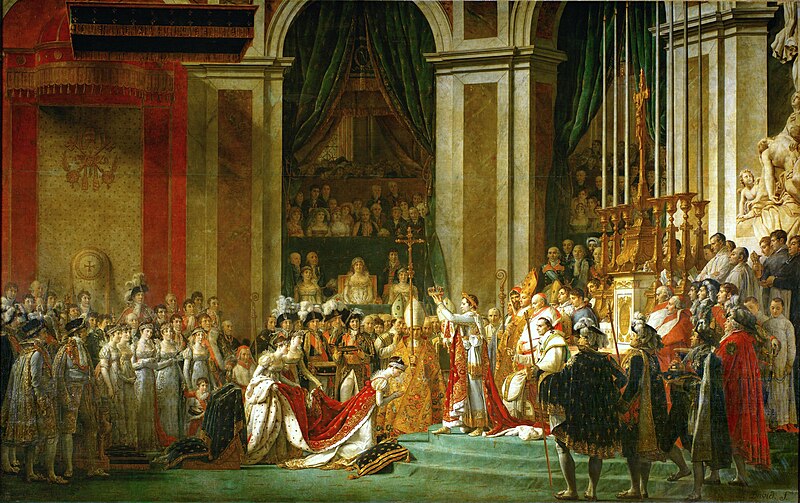

In a lot of ways, Napoleon seems to be Scott’s way of distilling the iconic images of the era into a tidy package. The contemporaneous paintings of Jacques-Louis David and other artists provide storyboards. The Battle of Borodino was already covered by 10,000 Soviet extras in Sergei Bondarchuk’s War and Peace, so no need to dwell on that. Details of clothing and uniforms are so precise that one of Napoleon’s actual hats that just sold at auction looks like it fell off the set.

Ultimately, sets, costumes and even actors are just tools in the world building of the visuals. The old rap about Scott — all spectacle no substance – is partly true except for the snobbery it expresses. Visuals are substance – it’s how we take in the world – and by that measure the film never fails. How is Scott so good at this? Men and horses dissolve into a bloody tangle as they fall through the ice at Austerlitz. Gold and gems gleam at Napoleon’s coronation. A single shot of Napoleon negotiating with Paul Barras to take over the French army includes tension between the two men, steam rising from a cup of coffee and in the misty background, like the distant horizon of a Courbet, a gardener tending to the yard. This isn’t a painted backdrop…it’s an entire tangible world, a cup of tea as consequential as a battleground.

I attended a Napoleon screening that happened to be in ScreenX which extends the projection along the side of the theater. It’s a fun way to watch a movie sometimes but in this case even though it was only used for battle scenes, it was unnecessary. Scott’s compositions are so perfect that they don’t need any padding. Instead, I’d advise seeing this on the biggest screen you can. Napoleon, Josephine and Ridley Scott all demand no less.