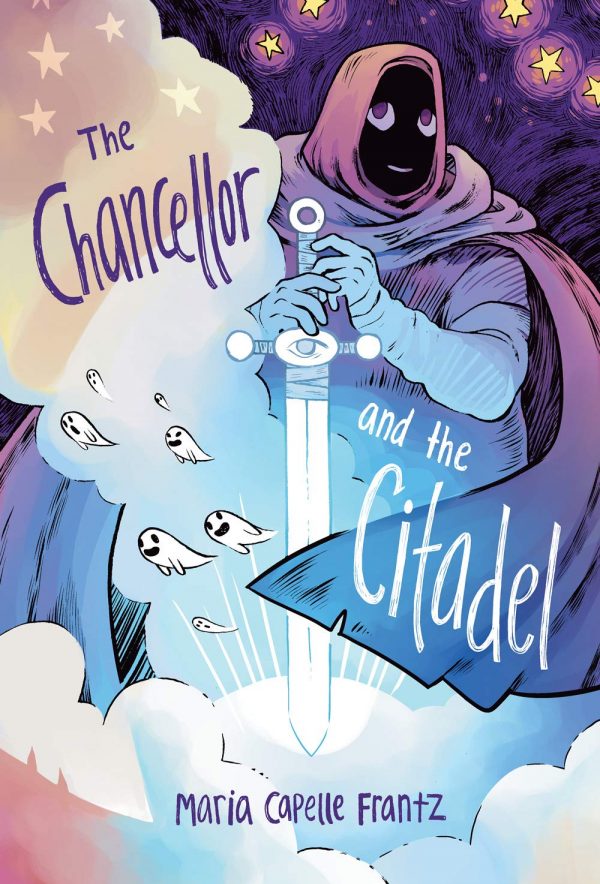

The Chancellor and the Citadel

By Maria Frantz

Iron Circus Comics

Presenting a fantasy scenario but challenging some stereotypes in the process, The Chancellor and the Citadel is about a mysterious magical being — the Chancellor — who protects the Citadel, aided by assistant Olive, and in service a community of people, mostly women. While the Chancellor’s air of mystery raises suspicion within the community, the truth is that the leader is filled with self-doubt and needs to do some magical

One of the most interesting things about Frantz’s story is her reliance on kindness and gentleness as the central quality of the protagonists even as they face danger. That’s a major about-face in fantasy fiction and genre comics, where things tend to evenly split between good and evil. In contrast, the Chancellor urges understanding of the enemy and advocates for equality rather than framing an antagonistic dichotomy that degrades the personhood of whoever is perceived as “the bad guy.”

If this sounds a little touchy-feely, I suppose it is, but it also works in bringing a completely different tone and core philosophy to the story. Fantasy, especially traditionally, was often about the clash of beings refusing to understand each other and acting on absolutes and accepted roles. Sounds a lot like Trump’s America.

But if Frantz is addressing close-minded hate, she’s doing the same with the idea of making up for it, the idea of true redemption, redemption that is worked for and sacrificed for. Coupled with the dazzling world she’s created visually, Frantz has fashioned a progressive fantasy that is defiant in not giving into cliches.

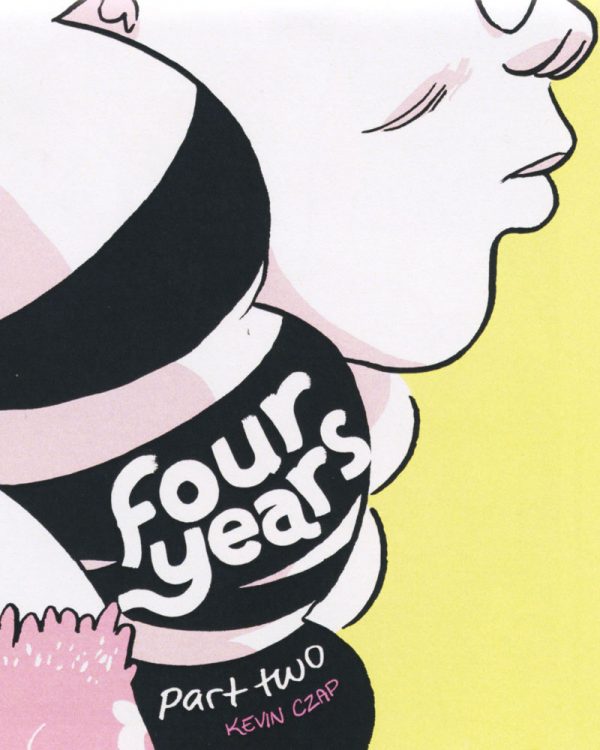

Four Years Part 1 and Part 2

By Kevin Czap

Czap Books

Boston gets all the attention, but as far as I’m concerned, Providence is the jewel of southern New England. It is literally the friendliest American city I have ever been to — that right there differentiates it mightily from Boston, where I lived for 14 years and continue to visit and can’t even remotely claim anywhere close to that. And unlike Boston, it’s still got its edge and its quirk.

Cartoonist Kevin Czap created Four Years as a tribute to their experience in Providence, where they now live. Following resident Betty Yaris on the day she gets her ears pierced — she’s 32 — Czap chronicles her interaction with her group of friends in a freewheeling, unstructured way that captures the joyous chaos of everyday life and of the energized chatter between people who love each other, with dialogue and cartooning working flawlessly together help the scenes wash right over you.

With two short issues, Czap is still setting up the character dynamics and plot, but letting these all unfold in an organic and empathic way that it’s much like being introduced to a new group of friends that you are slowly getting to know.

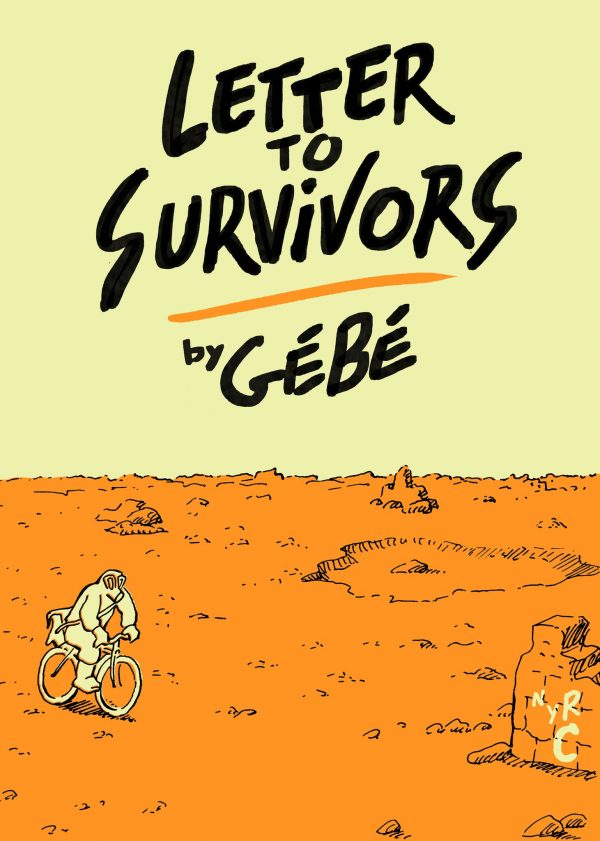

Letters To Survivors

By Gébé

New York Review Comics

Most post-apocalyptic stories don’t opt for silly surrealism as their central conceit, but Gébé (a.k.a. Georges Blondeau) revels in the choice. A collection of various tales traversing different eras and even fantasy worlds, Gébé uses the framing device of letters sent to a family huddled in their survival shelter as a way for the stories to be related.

The family is ill-tempered, sick of being trapped in a shelter, and the post-apocalyptic mail carrier who walks on the surface in a radiation suit and reads them their mail through a ventilation pipe has sent them into a further emotional manifestation of hell that they no longer want to endure. Sent by a mystery writer, the letters often address the passage of time and the world before it was blown away, which creates niggling itches that the mother and father need to scratch, bickering about their own behavior in regard to the destruction and picking apart the stories within the letters to raise doubt on any wider lessons they might offer.

My favorite story, one nestled within another completely different story, is “The Legend of King Jolly and Queen Glee,” which recounts the efforts of the kindest monarchs ever to ease the suffering of their subjects. But their solutions are so wrongheaded and witless that they end up making life more complicated and even painful for the very people they are trying to help.

Gébé brings all these elements together in a way that the tales function as a microcosm of the pre-apocalypse world, the one we live in, where reality is made what it is through multiple small stories over long periods of time that often collide or cascade, creating actions and reactions for new paths. The stories range from the hilarious to the melancholy, with the framing device of the family providing some conceptual groundwork that offers the reader more opportunities for follow-up philosophizing.