Femme Magnifique: 10 Magnificent Women Who Changed the World

by Various Creators

IDW/Black Crowne

This one-shot 10-woman digest version of last year’s extravaganza Femme Magnifique: 50 Magnificent Women Who Changed the World was put together for Women’s History Month. While it doesn’t contain new work, I think it’s a worthy effort to provide a more succinct summation of women’s contributions that actually ups the idiosyncratic quality created by the scope of subjects. If you already have the original book, there’s nothing here for you, but if you’re looking for a less expensive alternative as a gift for a kid who could benefit from these stories — or if you’re concerned that the big book is either too daunting for the kids in your life or just too big an expectation to drop on them — this is a great option.

Alison Kwitney and Jamie Coe’s bio of Margaret Hamilton — the computer scientist who worked for NASA not the actress in the Wizard of Oz — starts out the book and it’s a good example of the type of thing that needs to be accomplished by projects like these. Instead of just laying out what makes Hamilton magnificent, Kwitney talks about her exposure to female role models in popular media of the time, and how out of step those representations were — in other words, how suppressed within our culture the existence of women like Hamilton were, and how recently in our history that still took place.

Maris Wicks’ does an excellent job following up these ideas with her piece about marine biologist Sylvia Earle and her early struggles against sexism to be able to work in her field. As with the Hamilton story, Wicks’ experience contains popular culture downgrading the real role of women in important fields. When she becomes part of an all-woman team training underwater for NASA, they are trivialized by being called “the Aqua Babes.” By 1990, Wicks became the first woman to serve as the chief scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, so silly nicknames didn’t keep her down and American society just had to grow up.

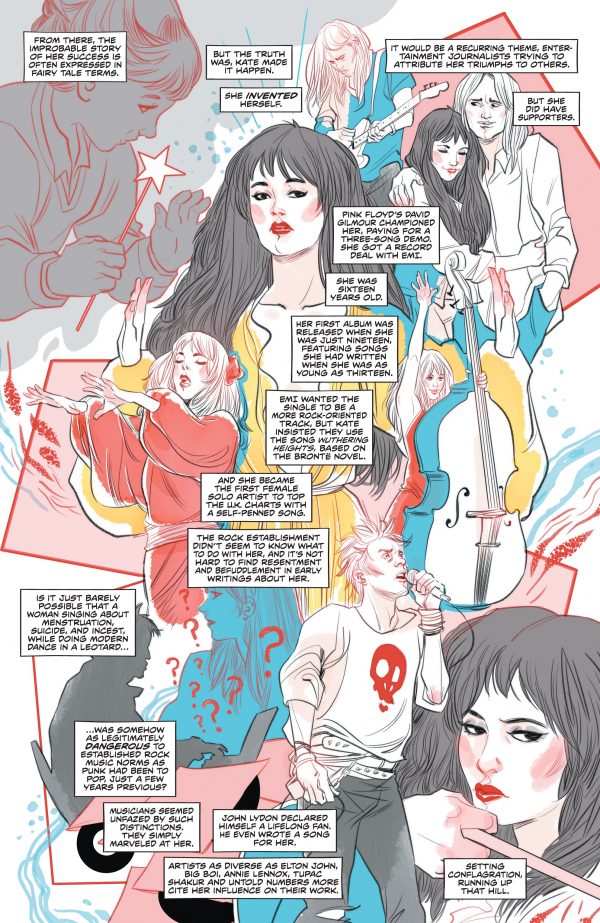

Gail Simone and Marguerite Sauvage’s Kate Bush bio is more a basic summation of Bush’s career, with context provided for its importance. It offers enough of the diversity of her energy and creativity and rightfully credits her as a groundbreaking female artist who created and controlled her own image and career during the decade before Madonna was wrongfully lauded as the original pioneer of what Kate actually achieved.

Casey Gilly and Jen Hickman’s meditation on Mary Blair is less specifically about the illustrator and animator herself, but about Blair’s impact on Gilly as a child and then an adult. No mention of her amazing work on Golden Books, for instance, it focuses more on her Disney output and its relationship with other macabre creativity — Gorey, del Toro — that has fueled Gilly all her life.

Lucy Knisley discovers the life of Margaret Sanger through her experiences with women’s birth control rights in high school, after witnessing the consequences of ignorance about the choices, and realizing the way information about that is kept from those who need it the most. Knisley is able to relate Sanger’s biography to her own life as well, and it’s a tidy summation of one woman’s huge influence on the most personal aspect of many women’s lives.

The Hilary Clinton section, by Kelly Sue Deconnick and Elsa Charretier, is more of a fable, and its abstract representation of Clinton as a figure of inspiration rather than the real aspects of her life is probably a wise choice. Depicted traversing a difficult, rocky road, it’s a touching tribute to someone who paved the way for women, many of whom are only just now coming of the age where they can show their power publicly and dynamically.

Jim Rugggives skateboarder Cindy Whitehead is a nice tribute that captures her energy and charming sass, while Cecil Castellucci, with Philip Bond handling the art, does well with Sally Ride, using her bio and resulting inspiration to give due to a number of other women in the space program.

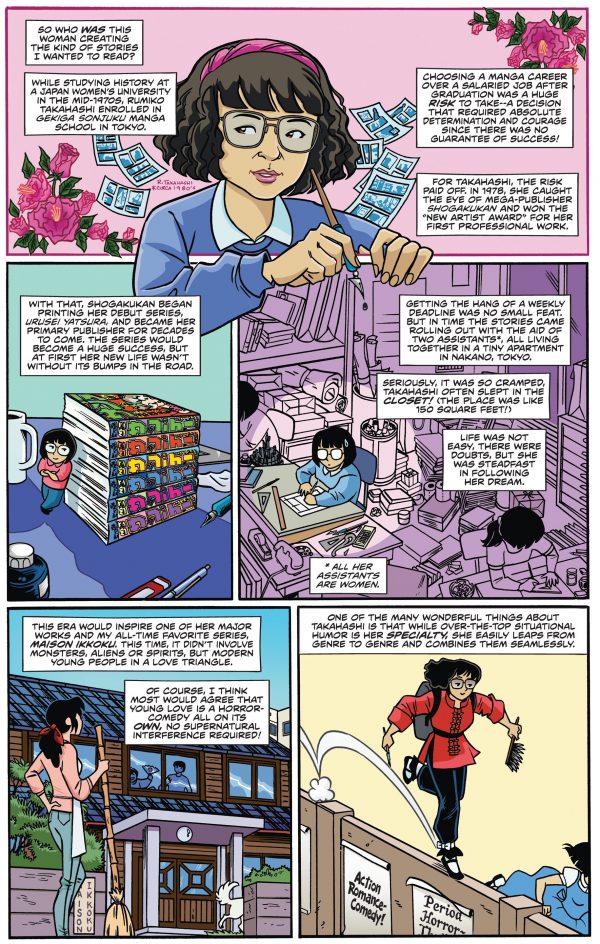

I loved China Clugston Flores’ piece about Manga artist Rumiko Takahashi, partly because of the energy and enthusiasm of the artwork in presenting the life of this woman who influenced Flores so great. But I also loved it because it’s the one time a woman in comics is addressed in this book, and it made me wonder about an entire collection of cartoonists writing about the women in comics who have influenced them. I honestly didn’t know much about Takahashi and would love to see more of this kind of thing.

The book winds down with a straightforward recounting of the life of Harriet Tubman by Chuck Browne, Sanford Greene, and Jordie Bellaire, focusing mostly on what could be called her origin story. That’s fitting, as there is an aspect to Tubman that is superheroic and I don’t think it’s overstating the case to say she was surely one of the greatest Americans to ever live, embodying all the traits we say we celebrate, and putting those traits to good use to help victimized people. So if it isn’t a mind-blowing entry, any opportunity to extol the power of Tubman is important and worth doing.

Has the artist who drew that Kate Bush page ever seen her, Dave Gilmour or John Lydon? The text is about as close to the truth too.

Comments are closed.