This will probably be the sentence that gets me flayed by half of the comic-reading nerds in existence but…I just don’t care about the X-Men. (Or at least I haven’t for a very, very long time.) I — like many other nerds of my generation — grew up with a deep love and respect for Chris Claremont’s X-Men and later, in my pre-teens, fell madly in love with Grant Morrison’s New X-Men. It was fresh and new and, while completely sticking to the notion that X-Men needed to spotlight on the turbulence of the the characters it contained, there was a bigger focus on what it meant to be mutant in the world.

After New X-Men’s end, I dabbled with Joss Whedon, Ed Brubaker, Brian Michael Bendis, Peter David, and countless others creators’ iterations of the band of justice-fueled mutants… but, for the most part, the majority read as angst-filled ghosts of the collective 1990s stories to me.

It’s not that the writing was bad! It’s undeniable that each person who’d dipped their hand into the world of the X-Men is absurdly talented and brought an important, identifiable message to those who live in the world of feeling oppressed and ostracized — but the concept stayed the same, relying heavily on character focus and empty promises of change. Every character wrestled with inner anguish and their interactions with non-mutant people, which sparked a haphazard attempt at revolution. Then a vague resolution appeared that made it easy enough for everyone involved to go back to being grumpy, until there needed to be another attempt at revolution. Mutants are a metaphor and humans are terrible, so the cycle continues.

To me, there was so much wasted potential by focusing almost solely on the individual characters. So when I was sent Jonathan Hickman’s House of X and Powers of X, I recoiled with a groan, sat down, and decided to give this another shot.

And holy cow — I’m really, really glad that I did because both House of X and Powers of X are definitely for people who are tired of X-Men.

[Warning: There be big spoilers for both series from here on out!]

Not only do the flowers grow these habitats, but they also spawn various types of powerful medicines that can be used by mutant and humankind alike — as long as international ambassadors are willing to see Krakoa as its own free nation.

This already feels like a very purposeful head-nod towards Morrison’s New X-Men, as both are visions of what the beginning of the future of mutant kind looks like. However, Hickman seems to take Morrison’s idea of “We are the future of humanity” and runs with it.

There has been a long-running theme of the X-Men attempting to assimilate, but House of X throws that idea right out the window. Mutants, and the life-giving powers which they hold, are done assimilating. But it’s not all a power-grab and fight against non-mutants anymore (YAY). Hickman has also taken it upon himself to create an actual, fleshed-out mutant culture complete with living habitats, environments, language, and medicine.

I choose to use the word culture in this instance because if you go to any anthropology nerd and ask them what makes up a culture, the concept revolves around a shared meaning that defines the group, a common language or learning through passive and active habits, patterned ideas that are similar in nature, adaptability in varying environments, and symbolism of representation.

Which is to say that somehow, within on issue, Hickman has managed to check every box and I’m completely shaken to my X-Men-doubting, comics history- and anthropology-loving nerd core. For example, it’s pointed out that the directions to each habitat are written in “gibberish” by one of the ambassadors (harkening back to the X-Men as a metaphor for racism and xenophobia) and is corrected by an eerily calm Magneto, who informs them that all mutants who live in Krakoa have been telepathically implanted with the new language. Not only that, but Krakoa appears to be its own living entity with several different environments to be adaptable to those who need them.

Essentially, in a way that is rarely seen done in even the largest scale of large-scale comics, Hickman has finally built the X-Men world that has been promised to fans for decades.

It’s not just about the damn-near immaculate world-building established in House of X though; it’s also about the ways in which the X-Men — both as a whole and as individuals — are further explained in ways that we haven’t gotten enough of in their previous iterations.

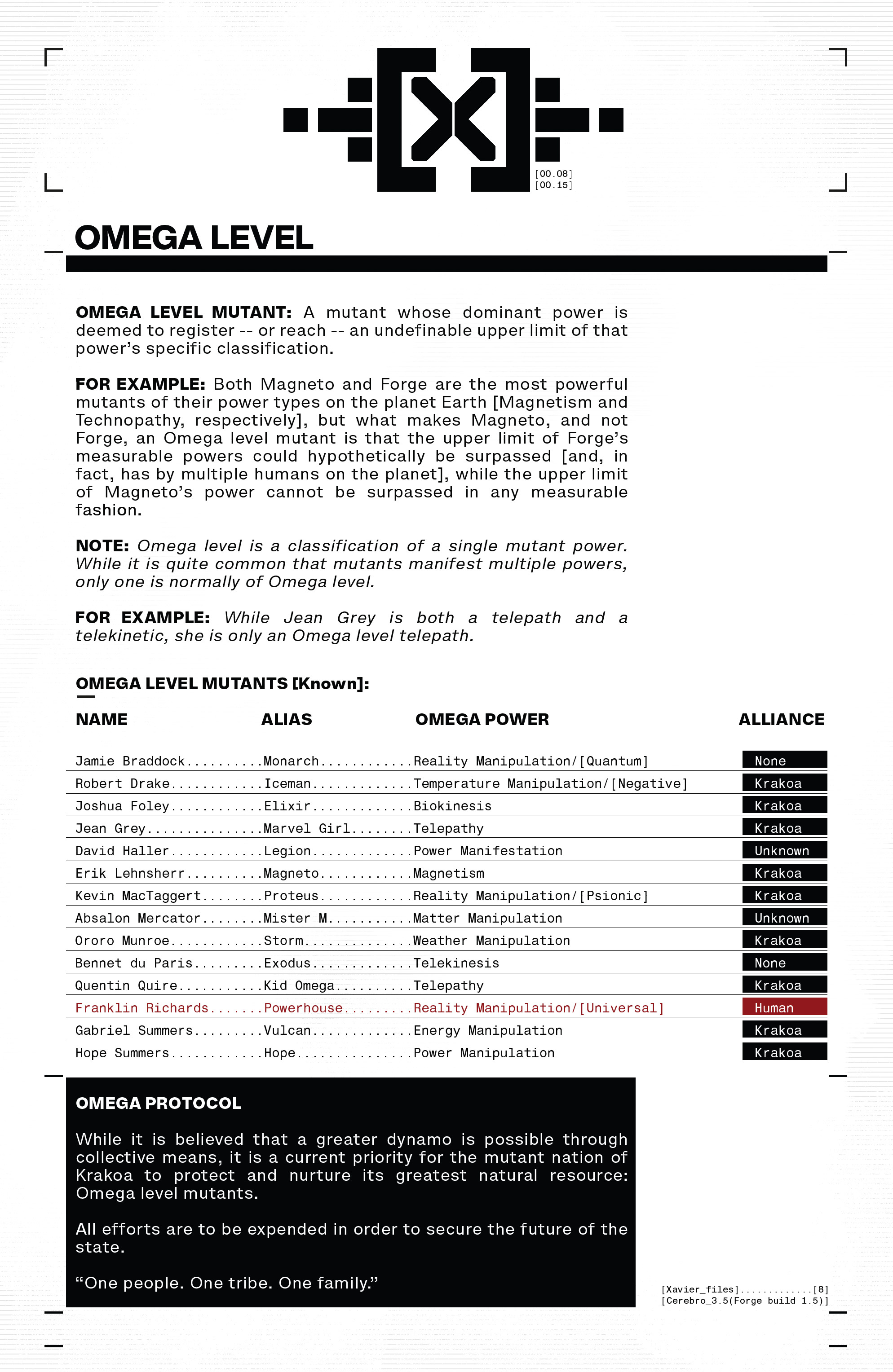

In addition to traditional comics panels, House of X features a number of governmental and scientific memos and documents that act as information dumps. The document that stuck out to me the most was one detailing what Omega levels are and which characters carry the label of being an Omega level mutant. There are all the characters that you expect (like Jean Grey, Legion, and Vulcan) but there are also the new additions such as Elixir and Storm. What this really boils down to is that Xavier’s file gives us the clarification of what being Omega means: it’s not the type of powers they have or how destructive the mutant is — but that there is no known limit to their superhuman growth.

This spoke to me as a way that character focus can still be used to set the scene without utilizing too many individuals. While we see plenty of the characters that we know (and several new ones that we don’t), they all seem to play a more collective role; combining into a culture of mutant peoples rather than a group of mutants squabbling over a snippet of common ground, and it pays off by allowing the intricacy of this new position in power to take center stage.

By combining all of these things, Hickman has taken X-Men outside of its own comfort zone. The team as we know it has always been something close to home and relatable; the superheroes who lived among us, spoke our languages, acted like us, lived out their fictional lives in our world, and could just as likely be training up their powers right down the street; but this is nothing close to that. This is what X-Men should have evolved into after establishing the comforts of the everyday.

But hey, if we’re talking about getting out of the general X-Men comfort zone, we should definitely start talking about Powers of X.

Often in history, when there is a meteoric rise, there is also a hard fall. It seems that Hickman has planned to flesh out the world well enough to tell the saga of an empire across two conjoined storylines.

Frankly, Powers of X came across to me as overwhelming at first, but after some rereading, I think it was entirely purposeful. In order to establish the context of the new House of X world but also the wibbly-wobbly-timey-wimey of it all combined, there has to be a field to sow all of the many seeds that Hickman has planted. Let’s face it: House of X alone would not have the breadth to do that.

I’ve heard some people say that Powers of X seems entirely pointless for knocking down a story that has only had a week to breathe, but honestly? I’d rather be confused and curious than bored and slogging through the same, tired storyline.

Sure, it’s a lot of information to take in. Fans who have been following X-Men in recent years may have mixed views on the new rules found in the universe. To me — as someone who spent two decades giving up on the X-Men because of tiresome tropes — this feels like a call home to the X-Men I remember loving.

Snap.

Comments are closed.