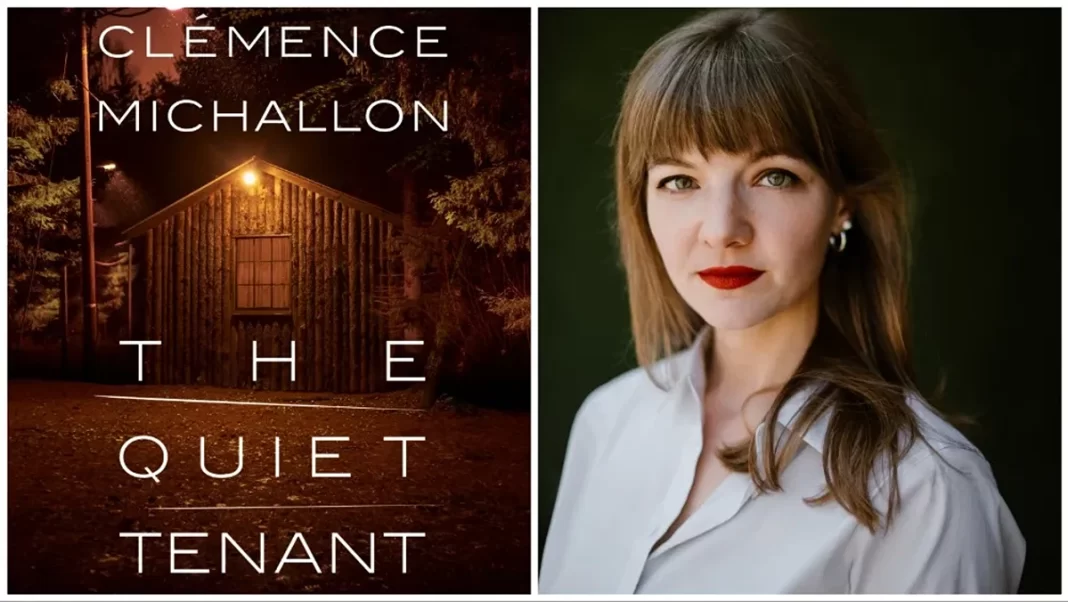

Author Clémence Michallon wanted to invert this approach to crime storytelling by turning the formula entirely on its head and letting the victims take the lead in her book The Quiet Tenant, a novel that lets other voices carry equal weight to prevent the serial killer from becoming his own island of relevancy.

The Quiet Tenant follows three women: Rachel, Cecilia, and Emily. Each one is impacted differently given the nature of their connection to Aidan, a serial killer that sexually assaults and kills women. Rachel is his captive, Cecilia is his daughter, and Emily is a woman who has a crush on him. Each character exists on their own terms, meaning they are not just what Aidan makes of them.

Rachel gets the most attention here, being that her presence considers the possibility of survival. Michallon’s genius here is giving the reader insight into her past, the things that came before Aidan. Her anxieties, her dreams and desires, and her failings are all there to show victims of serial killers don’t just become interesting the minute they fall into the web of a dangerous man. They have a history, a life that doesn’t begin at the moment they cross paths with a killer (something True Crime suffers from by not giving victims the chance to be more than their untimely deaths).

Emily and Rachel step in to complicate the very concept of the serial killer. Each manages to expand on the idea these men aren’t just murder machines embroiled in violence every waking moment. They also have a history, traumas, losses, and frustrations that inform their behavior. It makes the character of Aidan scarier, especially when considering such a disturbed being can be an okay father and have a love life that doesn’t always result in someone dying.

One last note, Michallon includes these short chapters in the book dedicated to Aidan’s past victims. They speak in the first person (like the three main characters), and they are heart-wrenching in what their suffering implies and how it builds up the pain a killer inflicts on not just one person but everyone that knows them. It’s a masterstroke in an already impressive piece of fiction and resounding statement on what the crime genre can do.

The Beat corresponded with Michallon to get at her methods in putting this measured but still brutal story.

RICARDO SERRANO: When a book as unique as The Quiet Tenant comes along, one immediately thinks of influences. In this case, I found myself thinking of the things you didn’t want your book to replicate or be a copy of. What things did you really want to avoid with The Quiet Tenant?

I ended up finding my balance quite naturally as I wrote the first draft. The violence in The Quiet Tenant is mentioned but not described in detail. There is no draft in which that violence is represented more explicitly. I found that there were lines I was simply not prepared to cross. What matters isn’t how the violence unfolds, but how it impacts my characters mentally. That’s what shapes their actions, and that’s what drives the narrative forward. So that’s what I focused on.

SERRANO: Do you think your multi-perspective approach is possible in True Crime stories? It’s a genre that’s struggled with giving victims a voice that carry equal weight to that of the killers and the investigators.

MICHALLON: Oh, absolutely. In fact, it was my own true-crime consumption that inspired me to tell the story in The Quiet Tenant by using multiple points of view. I noticed a shift in true-crime in which we shifted our focus away from perpetrators and redirected it towards their victims, as well as their relatives and friends—all people whose lives were affected by their crimes. That seemed to be a more meaningful way to think and talk about crime. When the time came to tell a crime story of my own, that influence came through loud and clear.

One example is the documentary Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer, which came out in January 2020. That documentary is based on a memoir called The Phantom Prince: My Life With Ted Bundy, which was written by Elizabeth Kendall, a woman who was Ted Bundy’s partner for a number of years. She is interviewed in the documentary, as is her daughter Molly. The documentary also features Karen Epley, who survived an attack by Bundy, as well as Bundy’s brother Richard Bundy.

It is very hard to tell the Ted Bundy story in a way that cuts through all the mythology that surrounds the case and takes you back to the very beginning: here was this man, who did these things, to these people. That documentary did that for me. I found it very impactful.

SERRANO: In what ways did writing the character Rachel surprise you? Did it all go exactly how you envisioned it or were there unexpected changes to her as the writing progressed?

I loved getting to know Rachel on the page. She is special to me, and it was hard to let go at the end. When I was done—truly done—working on The Quiet Tenant, I had this moment when I thought: “I don’t know what I’m going to do with myself if I don’t get to hang out with these people—Rachel, Emily, and Cecilia—every day.” I knew them so well by that point. Rachel was especially hard to let go of.

The main thing with Rachel was that I didn’t want Aidan to have been the only thing that had happened to her. I wanted her to have had a full life, with both joyful and painful elements. So I gave her a past. That past is a key element of how she has been able to survive five years of captivity by the time the novel begins: Aidan doesn’t know about her former life. He doesn’t realize that there are aspects of it that might help her. He underestimates her resilience, and the richness of her interior life. That might create problems for him down the line.

SERRANO: As you built Aidan’s character, the man that kidnapped Rachel, how did you land on the level of humanity you wanted him to be at? His interactions with his daughter Cecilia and Emily (the bartender who has a crush on him) are carefully constructed but not in a way that portrays him as a purely evil being that’s always on killer mode.

MICHALLON: When we read about people like Aidan (the—thankfully statistically rare—serial killers who maintain family lives), it is extraordinarily hard to hold all of their identities in our minds. But I do believe that we are all ourselves all the time. I don’t believe that one life is real and the other is not. This is what I was trying to work through with Aidan.

The multiple points of view were essential to exploring his three identities—the serial killer, the father, and the man who has managed to be known as a good neighbor around town. When writing Rachel’s chapters, I focused only on her perspective. When I was working on Emily’s chapter, everything shifted for me, internally: I almost had to forget what I knew about him, and place myself solely in Emily’s shoes.

David Chase once said this of his work creating The Sopranos: “I want to tell the story about the reality of being a mobster—or what I perceive to be the reality of life in organized crime. They aren’t shooting each other every day. They sit around eating baked ziti and betting and figuring out who owes who money.”

That really resonated with me. If you look at serial killers’ lives, you’ll realize that they spend most of their time not doing what they’re infamous for. The majority of their time on Earth is spent not killing people. They go to the grocery store, and they eat, and they have jobs, and they spend time around their relatives and perhaps their friends. There is something here that I can’t wrap my brain around. Or rather, I have—but I had to write an entire novel in order to get there.

SERRANO: What’s next for you? Hoping to explore more horror stories?

MICHALLON: I came to thrillers as a fan first, and I am delighted to be here. I want to continue exploring the genre. When I have an idea for a novel I might want to write one day, I never write it down. If the idea is important enough, if it speaks to me so much that I will want to stick with it for two to three years of my life, then I will remember it. I have about three ideas tucked at the back of my mind right now—and hopefully more to come after that.

The Quiet Tenant is now available wherever books are sold.