In my first column I detailed how House of X and Powers of X by writer Jonathan Hickman and artists Pepe Larraz, R.B. Silva, and Marte Gracia revolutionized the franchise and reinvigorated my interest in collecting weekly comics. TLDR: It’s the best X-Men story of the past 30 years. That said if you’d like to read that full essay (which I highly recommend because I wrote it and I crave validation) you can find it here. One conspicuous absence from my initial essay was any discussion of Moira X and the implications of the massive retcon surrounding her BECAUSE…

Artwork by Dave Cockrum, Sam Grainger, and Phil Rachelson. From Uncanny X-Men #96.

How do you solve a problem like Moira?

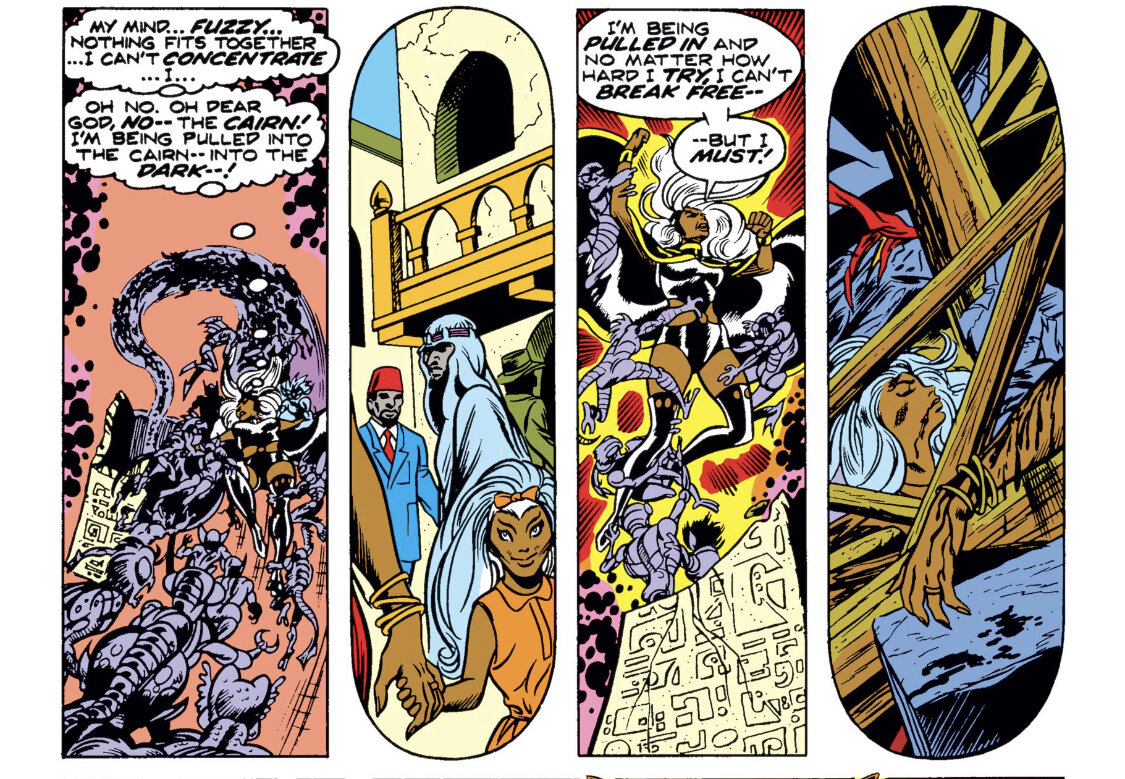

Read the above like you’re a group of nuns singing about Julie Andrews. Moira MacTaggart (to really deep dive into Moira’s whole deal, listen to the Cerebro cast episode on her here) is a brassy spitfire from her very first appearance in X-Men #96. Introduced to the X-Men by writer Chris Claremont as a sassy housekeeper with a working knowledge of assault rifles and later revealed to secretly be a Nobel prize-winning geneticist/former lover of Charles Xavier (COMICS!), Moira is one of the earliest “human” allies to the mutant race. Now almost 50 years after her first appearance we know that Moira is in fact a mutant with the power of reincarnation, a mutant who has lived collectively for hundreds of years, around whom the entire Marvel Universe seems to revolve, and yet only a handful of people know about her.

In House Of X #2 It is revealed that after every death, Moira reboots in the womb (seemingly rebooting the entire 616 universe as well) with all of the previous knowledge of her past lives. During her tenth life, Moira meets Charles Xavier at Oxford sometime before he founded the Xavier academy and the X-Men. Desperate to find a solution to the seemingly inevitable destruction of the mutant race, after centuries of failure — and an ominous warning of a waning window of opportunity from her precognitive mutant nemesis with gams for days, Destiny — Moira allows Xavier to read her mind and glean at least a partial understanding of her epic revolving lifespan. DEEP BREATH. Basically, without destroying any past continuity, this revelation changes everything.

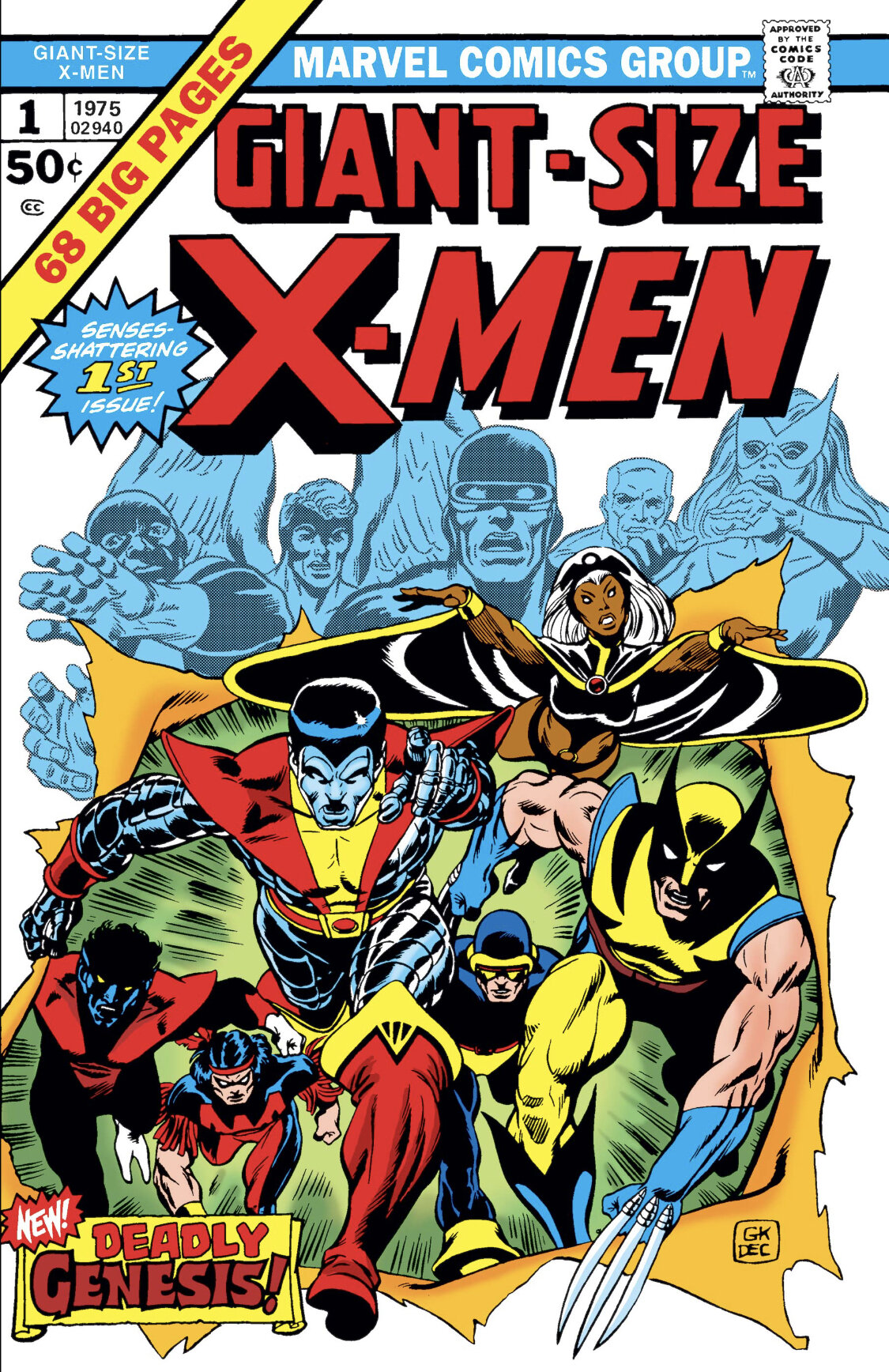

Giant-Sized X-Men #1 cover art by Gil Kane, Dave Cockrum.

The Grandeur and The Glory Begin Anew…

To get a real idea of how continuity-altering the Moira X revelation is, you really should go back to the genesis of the X-Men. Well, actually we’re better off skipping the first genesis and going right to the second. In looking at the X-Men as one long-running narrative (one of the longest continuous stories ever told) it’s actually best to start with the FIRST reboot in 1975. The first 66 issues of X-Men are definitely important, they establish the concept of mutant kind, Xavier’s dream, and many of the beloved characters that writers continue to develop today, but the narrative is a bit of a mess. The ’60s-era comics are a great read if you have the patience to navigate the archaic sensibilities, rampant sexism, and anachronistic ideas that come with them. All that is to say, skip the ‘60s run until you’re really in love with the X-Men.

Cracking open the hefty tome that is Uncanny X-Men Volume #1, the first omnibus collection of post-reboot X issues, I try to place myself back in 1975 when the Second Genesis of the X-Men began. Giant Size X-Men #1 with its oft-imitated Gil Kane cover featuring the new X-Men team bursting through the image of the terrified past could have easily led nowhere, but that’s hard to imagine now. It happens all the time to great books. Maybe the timing is off or the art doesn’t quite catch the eye…but something special happened with this one.

Since its cancellation with issue #66 in 1970, the X-Men title had been churning out reprints of back issues for five years, spinning its wheels as it were while also introducing a slew of new fans to the X-Men’s early exploits. When Giant Size hit the spinner racks, they weren’t necessarily forgotten, but mutants weren’t anywhere near the monolithic “intellectual property” they are now. Len Wein and Dave Cockrum (with a little help from a young upstart named Chris Claremont) reinvigorated the X-Men property with half a dozen new characters, some rejected concepts pitched for other books, others minor villains due for a refurbishment, and brought the mutant race back from the verge of extinction.

After Giant Size X-Men, Len Wein plots two Claremont scripted issues before he passes the torch to Claremont for X-Men #96, and for the next 16 years, Claremont would be the primary architect of the X universe.

Artwork by Dave Cockrum, Sam Grainger, Phil Rachelson. From Uncanny X-Men #96.

When approaching reading back issues of the X-Men some fans will tell you to skip all of the early stuff, and while I agree when it comes to the ‘60s (but seriously please read the Roy Thomas and Neal Adams stuff) I think the pre-Dark Phoenix era stories are essential to understanding the spirit of the X-Men.

It Comes With The Uniform

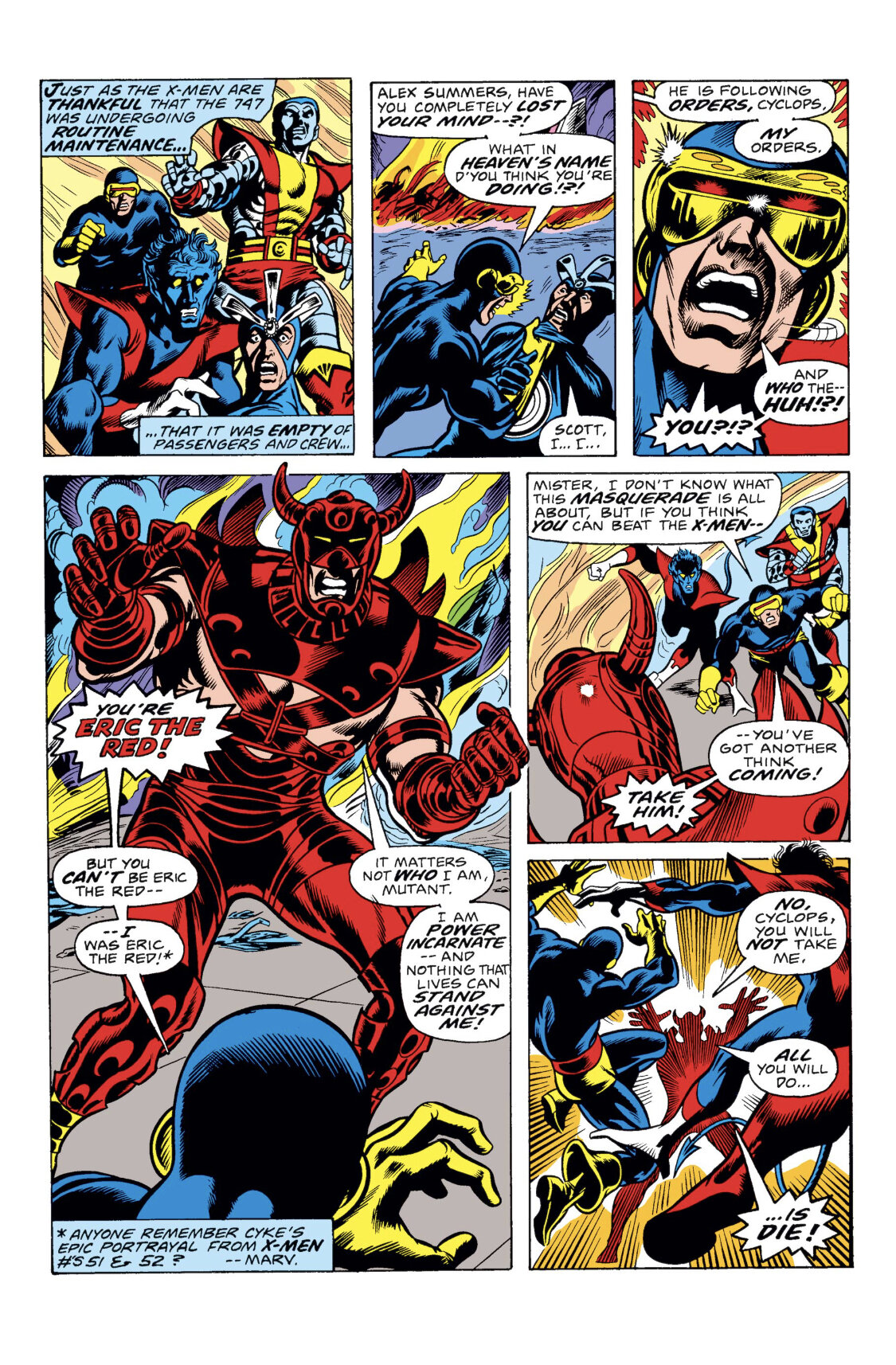

A lot happens in the first arc of the X-Men reboot and a lot of what happens will later be retcon-ed, but it’s still fun either way. Charles Xavier recruits an international team of mutants to rescue the original X-Men team from the living island of Krakoa. The ragtag team manages to stop bickering for long enough to form the first mutant power circuit, rescue the original team, and successfully launch Krakoa into space – for now – Krakoa gets better. The original team departs, Sunfire quits the team a handful of times, and in a conflict with D-list villain Count Nefaria, Thunderbird is killed.

It has been noted that the death of Thunderbird came about because of the character’s personality similarities to Wolverine. They are both introduced as authority bucking bruisers with chips on their shoulders the size of Krakoa, so to a degree, this makes sense. I do find myself wondering what the landscape of X-Men comics would look like had Wolverine met his demise in the explosion of Nefaria’s jet instead of Thunderbird. Would an indigenous American hero be one of the most valuable intellectual properties in the world? Or would we have just been subjected to a lot of highly suspect and racially insensitive stories featuring Thunderbird?*

After Claremont takes over, the X-Men fight a N’Garai lawn demon, bondage space Viking Eric The Red, Stephen Lang’s sentinels, sentinel versions of themselves, and Jean Grey AKA Marvel Girl sacrifices her life to save the team and is reborn as the cosmic being Phoenix. This is all in like 6 issues. To get in-depth coverage of this initial period (and everything else X-Men for that matter) you really MUST listen to Jay & Miles X-Plain The X-Men, it’s a long-running, top-tier X-Men podcast.

Artwork by Dave Cockrum, Sam Grainger, and Don Warfield. From Uncanny X-Men #97.

The death of Thunderbird and the death/rebirth of Jean Grey are shocking moments made all the more shocking when you apply Moira and Charles’ advanced knowledge of potential events to them. In House of X #2, a data page tells the reader that if Moira plays a passive role in events, they will play out as they have in previous lives. On panel, many events in Moira’s 4th life are shown to directly mirror events that take place in her 10th. With the knowledge that Moira and by extension Xavier have, it’s surprising that they don’t more actively try to prevent the suffering of fellow mutants.

This perhaps is reductive, or an oversimplified view of how things play out. It’s unclear to what degree things can be changed, as Moira points out when she reveals to Charles that mutants “always lose” the war for survival. Some events may in fact be inevitable — it’s easy to imagine the Phoenix force entering Jean Grey’s life regardless of earthly intervention — but in some cases at least, it’s clear that Charles and Moira allow terrible, perhaps preventable, things to happen to the innocent in service of “the dream.”

Can You, Cyclops?

Above all things, Claremont’s characters suffer. They have fun sometimes, sure, the occasional superpowered baseball game and Christmas in Manhattan, but primarily Claremont deals in angst, ennui, melodrama, and pain. In his first issue as head writer of the series, Claremont’s narrator berates Cyclops for his failure to prevent Thunderbird’s demise. It’s a classic series of panels that belong in the Comics Soap Opera Hall of Fame.

Artwork by Dave Cockrum, Sam Grainger, Phil Rachelson. From Uncanny X-Men #96.

Even before the Moira X retcon, Charles Xavier’s ethics are questionable at best and outright vile at worst. I mean, the man’s “dream” regularly involves training children as paramilitary enforcers, so there’s that. We don’t even have time to get into the Deadly Genesis retcon, listen here to get a breakdown of that nightmare. Xavier also shows a penchant for faking his death, often abandoning the children and young adults in his care to fend for themselves — sometimes as a test, sometimes for the “greater good” — other times to traipse around the galaxy with his Shi’ar lover Lilandra. With the addition of Moira’s knowledge, Xavier’s choices are straight-up Machiavellian.

While I do believe that Xavier (and Moira to a far lesser degree) believes he’s doing “what needs to be done” for the “right reasons”, they are both, at the end of the day, liars. Xavier withholds life-saving information from his friends and students on a regular basis, and his certainty in his and Moira’s methods is immensely hubristic. Xavier has always been a jerk, but when you apply yet another layer of subterfuge to his actions, it calls into question the heroic nature of the character.

Artwork by Dave Cockrum, Sam Grainger, and Don Warfield. From Uncanny X-Men #97.

Xavier claims to view the X-Men as his children but he still allows them to suffer immensely and not infrequently die. Since we are only privy to the interactions that we’ve seen on the page, we don’t know if Moira and Charles discuss potential ways to prevent the worst atrocities that take place in the mutant universe. It seems that in service of preventing the fall of the mutant kind, Xavier is willing to break a few eggs. Should Charles and Moira have intervened more often to prevent emotional and physical harm to those they claim to love? Would Xavier have been able to stop anything? Do his choices make him a monster? It’s a personal call, I’m still not sure.

That is all to say this is a very exciting twist on the character that sends ripples through years of continuity and in turn, makes reading back issues an even richer experience.

There’s Something Awful On Muir Island

One of the most damning and interesting new revelations in Powers of X #6 is presented in the form of Moira’s journals. Though some entries are mysteriously redacted, one entry that the reader is presented with details Moira’s plan to eugenically pair Xavier and herself with the ideal mates to produce a reality-warping mutant. The implication is that Xavier’s son David Haller AKA Legion and Moira’s son Kevin MacTaggart AKA Proteus are the results of these clandestine pairings.

THIS IS WILD. Proteus is a creation of Chris Claremont and John Byrne introduced as Mutant X in X-Men #125, after first being teased in classic Claremont slow-burn fashion in issues #104 and #119. Proteus is an immensely powerful and unstable mutant whose reality warping mutation also has the unfortunate side effect of deteriorating the physical body, requiring Kevin to either remain in stasis or instead grotesquely “body hop” through others, killing them in the process. In his initial appearance, Proteus escapes his confinement at Moira’s Muir Island research center, kills a surly hovercraft operator, kills his abusive father, and attempts to kill Moira before being fought by the X-Men and killed by Colossus. The whole situation is traumatizing and deeply tragic.

Artwork by John Byrne, Terry Austen, and Glynis Oliver. From Uncanny X-Men #127.

Moira’s intention to genetically engineer and employ eugenics to achieve the ideal mutant child is gross on its own. When paired with the suffering that Kevin went through on the way to Moira’s goal, it’s made near unforgivable. Moira and Kevin have yet to be reunited on the panel, but with Proteus acting as an integral member of The Five (the mutant power circuit required for mutant resurrection), it’s bound to be an issue when he discovers the truth about his conception.

Moira may not be a great person but she is a far more ethically complex character after the HOXPOX retcon, and I for one enjoy the complication. If Moira truly believes that her methods are the only way to prevent mutant Armageddon, is she wrong to do whatever it takes no matter how cruel? Yeah probably, it’s pretty messed up, but again, it’s up to each reader to decide what they can abide by in service of mutant survival.

Artwork by John Byrne, Terry Austin, and Glynis Oliver. From Uncanny X-Men #128.

Cover art by Dave Cockrum, Frank Chiaramonte, and B Wilford.

From The Ashes Of The Past, Grow The Fires Of The Future

These retcons (and the overall shift of the X-Men’s mission) have been difficult for some long-time fans of the X-Men to process, and that’s understandable. I personally love it all, because I believe it creates a more detailed and nuanced narrative for my favorite characters to occupy. Some criticism has suggested that the X-Men can no longer be “heroes” when their motivations, actions, and history are altered in such a major way, and I find that claim shortsighted. Superheroes are at their least provocative and useful when they are one-dimensional paragons of purity.

That isn’t to say I enjoyed the gritty post-9/11 bitterness of the early aughts, I find that extreme equally distasteful and dishonest. The complication of the mutant metaphor and mutants, in general, serves to make them more human. We contain multitudes, as do mutants, and to reduce them to narrow windows of heroism and villainy is a disservice. The X-Men have always been able to phase back and forth through the veil of morality with their identities intact and we should be glad for that.

*Notes On Race And Racism In The X-Men

If you are first coming to reading classic X-Men comics in 2022 there’s an elephant in the room that has to be addressed. All of these comics for many many MANY years were written and illustrated exclusively by white men and unsurprisingly the racial politics they contain are often an issue. In moments where perhaps the writers believed they were approaching race in a progressive and thoughtful way, they reinforce painful stereotypes and reduce large populations to insulting clichés. Other times the writers do not have the “best intentions” and they’re just awful. While I would like to say this is no longer an issue, to this day Marvel has major issues with colorism in regards to the steady lightening of character skin tones.

In general, the handling of race and the “mutant metaphor” in the X-Men is often problematic and complicated. While the new X-Men team introduced in Giant-Size X-Men #1 was far more diverse than the original five mutant teens, the production team was not, and it shows. The characterization of characters like Thunderbird, Storm, and Sunfire are steeped in racism and western tropes that can be difficult to read. Simultaneously, their inclusion on the team was a big step in a more inclusive direction for Marvel comics in 1975.

Unfortunately, when both Sunfire and Thunderbird are written out of the series before the Claremont run begins in earnest, Storm becomes the sole person of color on the main X-Men team for many years. While the “Mutant Metaphor” can be useful, it is imperfect and can not take the place of actual representation on the page and in the production team.

With Storm, Claremont does a lot of work to write a nuanced and exciting leading character that he clearly respects and cares about, and he of course does not always get it right. The cringy moments of the Claremont run (there are certainly a lot of them) SHOULD be dissected and critiqued. While I can easily weigh in on queer and gender politics in X-Men, as a white person I will not always be the best person to parse the racism, but I will do my best. There is a lot of writing on this subject by folks more qualified than I and when applicable I’ll link to pieces on the subject in future columns.

What are HEROES OF X and HISTORY OF X?

Buy Uncanny X-Men Omnibus Vol. 1 Here!

Micheal Foulk is a non-binary queer writer, comedian, and organizer thriving in Oakland, California. They are the co-host of I’m Not Busy — a weekly podcast with Vanessa Gonzalez — the co-creator of the LGBTQ+ storytelling show Greetings, from Queer Mountain, and the curator of the film screening series Queer Film Theory 101, produced in collaboration with Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas. Their work has been published in Slate, Vice, Into, and TimeOut NY.

Micheal will make you a playlist if you ask nicely.