DC Comics is trying something new. In the wake of their Rebirth initiative, the publisher has rapidly expanded its content to include diverse new imprints such as Young Animal, Wildstorm, Jinxworld, Wonder Comics, Black Label, Ink, and Zoom. As their lineup expands, it can be hard to figure out what to pick up each week. That’s what our team is here to help with, every Wednesday, with the DC Round-Up!

THIS WEEK: Louie goes rogue and likes Heroes in Crisis!

Note: the reviews below contain spoilers. If you want a quick, spoiler-free buy/pass recommendation on the comics in question, check out the bottom of the article for our final verdict.

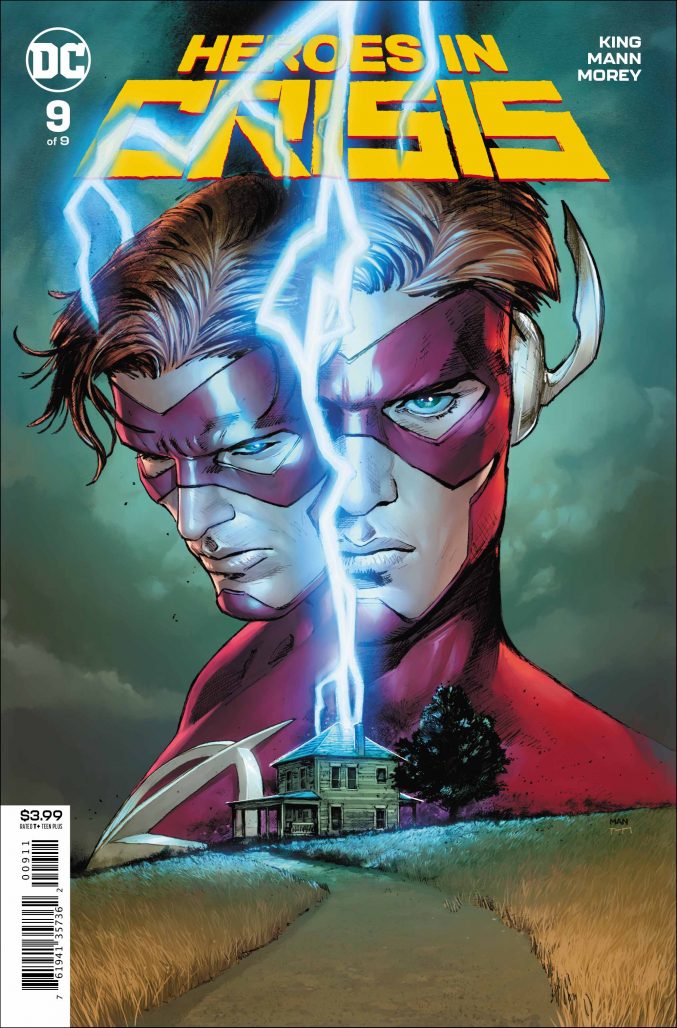

Heroes in Crisis #9

Heroes in Crisis #9

Writer: Tom King

Artist: Clay Mann

Colorist: Tomeu Morey

Letterer: Clayton Cowles

And here we’ve come to the final issue of what is certainly one of 2019’s more challenging books to review. After all is said and done, did Heroes in Crisis live up to the hype? Let’s take a look.

You may recall that the launch of this book last year was pretty rocky. From the start, Heroes in Crisis had a serious marketing problem. We’re talking about a story about a mass killing with at least a dozen victims, and yet DC seemed strangely hellbent to frame this as a fun murder mystery story, putting out teaser ads that asked the reader to guess who would die. In a time of volatile mass shootings, the publisher’s kind of glib PR approach to a story of this emotional weight was questionable at best. It didn’t help that the book was saddled with the “Crisis” buzzword, which itself brings along decades of baggage and expectations and further confused the audience about the type and scope of the upcoming story. We saw Dan Didio and crew jokingly teasing at comic conventions that “you can’t have a Crisis without a dead Flash!” as if to stoke up the fan speculation engine a bit before turning the mic over to writer Tom King for a minute to remind us that this is, remember, a serious story about a very serious topic.

On top of readers not being able to decipher the mixed PR messages in preparation for the first issue, there was absolutely no in-story setup leading up to the event launch. This was the complete opposite of 2008’s Final Crisis, which had an entire year’s worth of groundwork in the form of the weekly Countdown to Final Crisis book that (supposedly) introduced the readers to the core concepts that would be explored in the main event. Instead, we were informed that Heroes in Crisis would focus around a significant new setting, the mental health facility Sanctuary, that for some reason had never been seen before. Having such a new concept be the centerpiece for the story was jarring. It would have been helpful to see a few scenes of the superhero trauma center working as designed within the context of the regular titles before exploring its sudden and gruesome undoing in this book. It was all so rushed and, again, confusing. Oh, you know that Sanctuary thing you’ve never heard about? Well it’s gone now.

Beyond even the myriad of marketing blunders, the first issue didn’t do itself any favors in bringing the reader up to speed (pun accidental, I promise). We jumped into this story after the massacre had already happened, but we didn’t get a lot of details about what actually…you know, happened. Superman stood in a field of bloody bodies, only a couple of which were identified. Batman, the world’s greatest detective, stood back from the crime scene spouting platitudes about vengeance instead of analyzing the evidence. There was no discussion of the types of injuries, or possible weapons used, or a list of suspects, or possible motives. Nothing. It’s incumbent on the creative team, including the editors, to make sure the readers are clued in on the important story parameters. Who were the victims? What clues do we have? WHAT IS SANCTUARY? I went into the first issue expecting a “whodunnit”, but finished it with a feeling of “whatdunhappened?” After months of hype and speculation, the collective reaction from the comic reading world was one of being unsettled and disconnected from the story in progress.

But you know what? None of that matters in the long run. Despite the ill-advised marketing campaign, and despite the lack of setup, and despite the rocky rollout, and despite whatever that weird San Diego boat spa thing was, this series accomplished something really important between its covers that will certainly read better after there’s some distance from all of the public relations missteps. I’m choosing to review this book with fresh eyes, ignoring the corporate spin that mismanaged my expectations and looking solely at the book itself and what it accomplished. And you know what? I think it was pretty damn good!

Was it perfect? That’s a stupid question. Even those things (and people) we love dearly aren’t perfect. Name a “perfect comic” out loud on the internet and then brace yourself for the reaction. Obviously there are some rough edges on this one, as outlined above. A better question is: did it make me think or feel something new? Did it approach the concept of superheroes from an angle of exploration and respect? Did this book add anything? Though I might find myself in the minority, even among reviewers on this site, after reading and re-reading this series I have to answer with a resounding ‘yes’. There’s a ton of good stuff in this book.

The sequence of events, once you wrap your head around it, is tight, consistent, and clever. It was a little bit confusing on first read, due to having two versions of Wally West present for the climactic moment. But the story does a great job of explaining Wally’s timeline for those who wish to sort it out. Here’s his throughline in a nutshell, as we learned in the previous issue: Wally loses control temporarily, killing nearly everyone at Sanctuary in an instant. Horrified by his act, he makes a short jump forward in time to find his future self, waiting. This future Wally has all of his memories, plus five painful days. The younger Flash kills this older, wiser Wally and then jumps back to live out those five days himself (which he uses to expose Sanctuary’s files and record his own confession, in an effort to show those who are hurting that they are not the only ones, that there are others going through the same thing and getting help). And then he waits in the field for the younger version of himself to come finish it once and for all. While this should have been the tragic end of the Flash, in this final issue we learn that the older version of Wally actually talked his younger self out of committing this strange form of delayed suicide. It all works with what we’ve seen in the story, it doesn’t break any obvious rules of time travel, and it leaves Wally in an interesting position at the end where he now has to answer for his crime.

This is the part where you complain that this comic “ruined” Wally West. I get it. We don’t really want our heroes to change. We don’t want our lives to change. Change is upsetting. I myself wrote about how great it was to have a hope-filled Wally back in the DCU after he was reintroduced in the post-Rebirth continuity. We love Wally and it’s a hard pill to swallow to see his story go in such a dark direction. But we’ll see what happens next, right? Drastic changes are completely un-stomachable if the new status quo doesn’t serve some greater storytelling purpose (see: Grayson, Ric). If Wally just rots in a jail cell off-panel and doesn’t get used again, then this book won’t age very well and we’ll all riot. But what if this opens up an exciting new avenue for telling stories about heroes who make mistakes? Or about having hope in a place where all hope seems lost? It’s uncomfortable to look at the darker side of the superhero life, but doesn’t it seem somewhat more realistic to think that they, even more than we, have some really low lows to deal with?

Whether that part of the story landed for you or not, don’t make the mistake of overlooking the other parts of the book. I’d argue that the time-hopping Flash meltdown was only of secondary importance. The real story was Booster and Beetle hanging out on the couch, drinking beer and taking their minds off the heavy stuff for a moment. The real story was Barbara finding Harley and convincing her to calm down and let her help. Despite whatever the DC Comics PR machine told us, this is actually a story about real life crisis. Where do you go when everything falls apart? Who is there to support you? How far would you go for a friend in need? The DCU is better for having these themes explored, and the presentation has been compelling and heartfelt and downright fun. Bros before heroes!

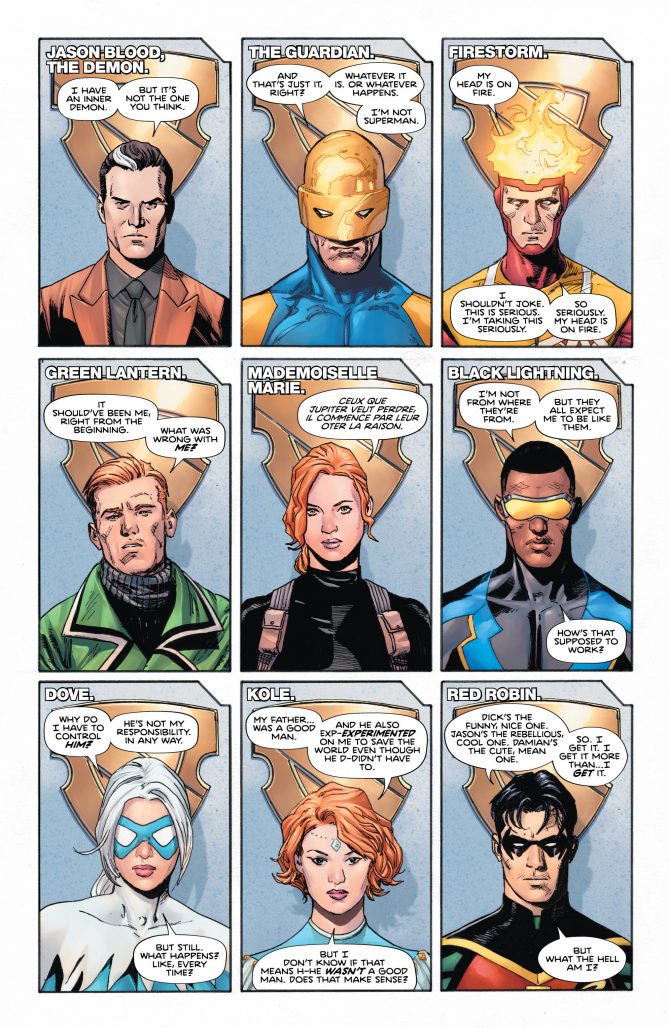

We also got a glimpse into the more personal thoughts of our favorite DC heroes & villains through the creative team’s use of the nine-panel confessionals, which helped to build the story’s emotional setting. Throughout the nine issues of this series, various characters shared their innermost demons and wounds that they had collected over the course of the adventuring life. It’s the type of characterization that wouldn’t fit neatly into any random story arc, with some heroes breaking down in tears mid-sentence and others barely concealing their emotions under a thin veneer of nervous humor. Roy Harper tells us about his road from pain pills to opiates. Batgirl shows us her physical scars while Solstice struggles to control the thing inside her that wants to come out. Appropriate to the theme here, the telepathic Martian Manhunter lets us in on a secret: “Underneath, everyone’s screaming.”

And that’s the point, isn’t it? Watching these confessionals and seeing the heroes relive those pivotal moments that consume their thoughts, we’re reminded that they are supposed to be stand-ins for us. We’re all screaming underneath in some fashion and we all know what it feels like to have a personal crisis. If we’re lucky, we also know what it feels like to have the support and love of close friends, and to be able to lean on others when all we want to do is fall apart. Heroes in Crisis isn’t a murder mystery and it’s not a fun superhero adventure where the good guys save the day. It’s a gut punch to the emotions, if you’ve got them.

Obviously this is a story about healing, but maybe it’s more about just moving forward with the pain. Wally had a moment of weakness and did something bad. Really bad. The book’s title, it turns out, is completely appropriate. But instead of dying in this Crisis, the Flash has to live. Which is really much harder. He has to live with his failure, unable to run away from it. That pain will always be there and hopefully his friends will be too.

If you’ve never felt this way, then Heroes in Crisis may not be the book for you. And that’s fine. There are plenty of other books out there. But come back to this one during the hard times and see if it resonates. If so, you’re not the only one. And you are not alone.

Verdict: Hard Buy

Miss any of our earlier reviews? Check out our full archive!

Heroes in Crisis #9

Heroes in Crisis #9

I respect and agree with you from the perspective that it’s an interesting to read the turmoil and stress that the characters have to go through. And I like the concepts of Sanctuary, and a story that explores it.

But, the contradiction of his actions and who Wally West is, I just can’t get past. The murders occurring accidentally when he breaks? I can sort of swallow that. But, the cover-up and framing? That is just so far afield from a character with 50 years of history. Wally, to me, has always been that “everyman” character that fits in with the God-like JL’ers and the street-level heroes both. He is the bridge character. And I don’t see how this story doesn’t taint him for a good long time. It has to be the central defining trait of any appearance going forward. And it’s just not who he is.

Can we laminate this review as a near-perfect embodiment of modern super-hero comics?

“Yeah, it’s really not well written in some very basic ways and doesn’t actually make sense when you think about it and it turns a beloved character into a murderer for no meaningful reason…but look at all the grown up stuff it does with these characters and concepts that were created and intended for children!!!”

If you want to read a story that deals with post-traumatic stress, why not read a story about a REAL PERSON who experienced it? Or at least a fictional story about a realistic characters who went through a realistic situation? Why do you want to get that story through the lens of people who dress up in skin tight costumes, call themselves by ridiculous names, and run around “fighting evil?” Why aren’t you reading something for genuine adults?

Old-man-yells-at-cloud-rant over.

Mike

@Mbunge I totally agree with you, it’s like someone is desperately trying to mix two completely different target audiences and missing the mark on both.

Super-hero comics should be over-the-top fun and light-hearted, sure they can make you think, but if I want to hear about real life, I watch a documentary or read the news.

Blame it on Alan Moore to start a trend that lesser writers misunderstood and mishandled to the nth degree. It has to stop. I haven’t really enjoyed a DC comic since Giffen’s JLI.

Good thing the silver/bronze age is here to sustain me.

I respect that you and others enjoy the series. I read only issue 1 and realized I had no taste for the subject at hand. When it comes down to it, as a commercial enterprise and entertainment medium, I just don’t want to support with my money a story about mass murder by superhero. Now it turns out the story is a little more complex than that, but it still boils down to this. Some people manage their pain, but then we’re supposed to feel sympathetic for the guy who has a mental breakdown, wants to expose the whole “system” as a fraud, accidentally murders a few people, and then goes to commit suicide/murder again as a means of amends? Sorry, but that’s so downright depressing I don’t want any superhero’s name attached to that. Whether the writing or art is competent is irrelevant to me. Some readers may enjoy seeing that their superheroes are “just like them” with all the broken and hurt inside, but the best stories are those that show the hero fighting this broken human nature and doing good in the world. What we get in these confessional scenes is just a shallow look at what it must really be like to be a superhero. Here’s the catch though – it’s fun to point at Tim Drake for example and have him question his role in the world (after all, how many Robins does the world need?), but he’s just a fictional character in a fictional world who’s marginalization in the Bat Family is an editorial/publishing decision. He isn’t ACTUALLY marginalized in his world, he’s marginalized in our real world. And yes we can look at all the terrible stuff Superman has to witness and feel sorry for him, but his defining characteristic is that he rises above the suffering of humanity to lift up his world. And we certainly don’t need the Flash to murder people to get these “insightful” looks at all the DC heroes. A more well planned out story would have actually been about heroes going to Sanctuary and confronting their traumatic experiences. What “Heroes In Crisis” gave us instead was a murder mystery sprinkled with moments of fake concern for the heroes and villains who were (mostly) killed in the very place they were seeking treatment. Where is the real world analogy there? War vets who commit murder suicide at their treatment centers? Police officers who murder? I don’t see it. I feel bad for our real world “heroes” in crisis, but I don’t feel bad one minute for Tim Drake, Clark Kent, Bruce Wayne, Wally West, Gnarrk, or Booster Gold. They are characters and plot devices meant to tell fictional stories, not have to consider the “real world” implications of all the brokenness they see on a daily basis. (Okay, I feel bad for Barbara Gordon for being a plot device in Killing Joke.) It would be like asking your doormat what it feels like to be looked over and stepped on every day – must be pretty depressing, right? Sorry for the rambling, but that’s my opinions of the whole venture. Others obviously are entitled to their opinions.

I agree with you. I think it was a great book. What I’ve found a little bewildering about a lot of the negative reviews is they’ve acted like Wally’s coverup is monstrous and incomprehensible. It isn’t. He knows that Barry and Batman will solve the crime. He just wants them to solve it a bit more slowly, so he can leak the information about Sanctuary to the world (through Lois Lane) and so have some control over how that information gets out but also try and challenge the idea that trauma is suffered alone and away from public eyes. The reason that the intervention by the other characters allows him to keep living is that he sees that even in the midst of his bad decision making, as a result of his most damaging trauma, he was still able to catalyse some meaningful connection. This is a beautiful and heroic thing to have done, and it’s quite consistent with the Wally from the old Flash books, who was always getting lost and always finding his way home through his link with Linda. Letting him struggle and suffer but also act in a heroic way—however muddled his motives may initially be—lets those of us who liked the stories with his kids (which given how badly those books sold, and how much rage was directed towards Daniel Acuna for drawing them, was not a huge number of people) at least the satisfaction that these narratives happened and that his grief and loss are real. We haven’t had that kind of acknowledgment of ambiguous loss in superhero stories about retconned kids before, and I find it quite touching. I loved it when Wally came back in Rebirth but I did wonder what was going to happen about his kids; while it would have pleaded me to see them come back, I think the story of Wally grappling with what he’s maybe never had in the first place is a good one, and I’m glad it’s being told in this way. Of course we can think superheroes shouldn’t be doing these sorts of themes in the first place—I respect that position—but there’s no question they get to us. This is a story about the ways in which they get to us, because Wally is someone left utterly bereft by changes to continuity. A lot of superhero readers feel that way too: difference is that in the story Wally tries to do something with his feelings of loss.

@MBunge, you so eloquently wrote what I was attempting to say. This story is not good just because it’s profound. On a basic level, it is bad comics storytelling because it breaks the basic premise. Much like the Hydra Cap story broke Steve Rogers in a way that can’t be fixed. Every story written about Wally West after this will have to acknowledge that he did some very bad things to cover up his accident. And all this to tell an allegory about the traumas of war? If we want to start treating comic book superheroes like real people, then why AREN’T they all locked up for fighting crimes in spandex? Why isn’t Bruce Wayne arrested for child endangerment? Why isn’t Wonder Woman arrested for regularly breaking diplomatic agreements? How does Superman ever have time to eat or sleep? Who pays for all the broken infrastructure the heroes break? When does Batman actually have time to work at Wayne Enterprise? What actual board of directors wouldn’t know he was giving all the money to Batman? Speaking of spandex, why doesn’t it all get torn to shreds by just one time falling on the ground? I skinned my knee and tore up pants all the time as a kid. How does Batman recover physically to continue fighting crime? Let’s tell a story about how Bruce Wayne becomes a quadriplegic from his body breaking down. That’s realistic!

I would disagree with the reviewer’s statement that we don’t want our characters to change. At least for fans of characters like Wally, we loved watching them change. Seeing Wally go from Kid Flash to cocky neophyte Flash to married Flash to dad Flash was cool. Seeing Wally become a killer who covers up his crimes is not cool. Keep in mind, this was all done while we have Barry Allen being the perpetual staid forensic scientist that he’s been since the 1950s. If anyone is against change, it’s writers and fans who want to preserve the silver age status quo at the cost of legacy characters.

You say: “it doesn’t break any obvious rules of time travel”. I have to disagree. First, let’s assume a “closed loop” time travel philosophy (à la “Terminator I”). If younger Wally doesn’t kill his older self, then he (the younger one) will return to the past (with the cloned body, etc) KNOWING that he won’t commit this weird form of suicide (that is, knowing that in five days, when he’s already his older self, the younger one will travel from the past but won’t kill him). This ruins all of the emotional impact associated with older Wally about to be murdered by his younger self, and the scene between the two (and its dialog) just doesn’t make sense. If, on the contrary, we assume an “open” time travel philosophy (à la “Back to the Future” or even “Flashpoint”), then the story just occurs once and/or it doesn’t make any sense. (If younger Wally is arrested in the “past”, then no one goes to the “future”… next time. Actually, older Wally will just be younger Wally after five days in jail.)

Damn! I made a mistake. Thinking about time travel hurts my brain. Now I see that one Wally is arrested in the “future” and the other Wally goes back to the “past” (with the cloned body).

But, yet assuming an “open” time travel philosophy (as I said, the “closed” philosophy ruins all the emotional impact), we will only have the emotional impact (and this version of the story and this dialog) the “first” time. “Next” time, older Wally will know he won’t be killed.

Anyway: which Wally goes to the “past” and which one stays in the “future” ? It seems older Wally is arrested (better in jail than dead) and younger Wally follows the plan (goes back to the “past”, etc). This almost “fit” a closed loop philosophy and feels like it (even when strictly it’s not). But… it could change “next” time! In this “open” philosophy, any change (even the smallest) could change it all. Barry knows it well. My point here is: “open” time travel is always a mess. And traveling to the future and then back in time (having talked with your older self and knowing how the future “should” be, how supposedly it “is”) is so risky as just going back to your own past.

While I think many of the concepts in this book are interesting, the execution is terrible. For one, it seems to subscribe to the trauma = mass shooter equivalency that plagues our media and our society. For another, it frames a trauma victim as using gaslighting on characters in order to turn them against each other. While this is not to say that people who have suffered trauma cannot be manipulative, it is absolutely not a good light to paint this in. For a comic that claims to be a nuanced take on trauma, it sure does make a mockery of it. Rather than treating Wally (and others) as a character who has suffered and is trying to heal, it frames Wally as someone who is manipulative, putting his guilt above the safety of others. Which is not only out of character, but in my eyes contributes to stigmas about trauma victims. Finally, the book seems like a BIG middle finger to Rebirth and the good will DC accrued with the initiative. Wally West was the lynchpin of rebirth, and by breaking him(and yes, he was redeemed, but bloody BARELY) you are saying “That rebirth thing everyone loved? Yeah, we’re not doing them anymore.” This comic, like much of the recent Snyder stuff reeks of DiDio going back up to his old shenanigans now that Johns is no longer an executive. “Geoff is no longer here to protect Wally? Hooray! Now Barry gets to be the only Flash again!” is probably something DiDio said. All in all, this concept had a lot of potential, but lived up to all of my worst fears. It also continued the trend of me not wanting to read Tom King comics anymore which began with The Gift story arc in Batman. (Ironically, a setup for this story)

Finally, Wally West is written and treated with pathos in the way Aristotle defined in his Poetics. Doesn’t get much better, and I expect Hegelian unity, and the satisfaction (just looking from the art, I know it). And the 9 panel grid, building and mainlining multiple perspectives as mainlining narrative… just, sweet, this Modernist technique that serious novelists/writers employ

and King pulls off in concise visual-manner, with aplomb. Other comic writers have tried to pull this off in similar style (like Tim Seely, who worked with King on Grayson, and uses it in his own work) but not have not captured what King has, at all. That’s skill.

I see pathos and mimesis in abundance, and crafted well in a developed narrative with Modernist sensibility crafted well for the comics medium. Beautiful art, everything.

The world can burn but I care about good Art (subject matter is practically irrelevant, except to that purpose), and attachment falls away in the face of it. Splendid! thank you very much (it’s good to see, see how other people see, and see. See?

To aid what I mean when I say King is doing astonishingly good Modernism in his comics (particularly Batman, but his writing generally):

[from wikipedia, on literary modernism]

*Early modernist writers

Early modernist writers, especially those writing after World War I and the disillusionment that followed, broke the implicit contract with the general public that artists were the reliable interpreters and representatives of mainstream (“bourgeois”) culture and ideas, and, instead, developed unreliable narrators, exposing the irrationality at the roots of a supposedly rational world.[11]

They also attempted to take into account changing ideas about reality developed by Darwin, Mach, Freud, Einstein, Nietzsche, Bergson and others. From this developed innovative literary techniques such as stream-of-consciousness, interior monologue, as well as the use of multiple points-of-view. This can reflect doubts about the philosophical basis of realism, or alternatively an expansion of our understanding of what is meant by realism. For example, the use of stream-of-consciousness or interior monologue reflects the need for greater psychological realism.*

It is my thesis that the entirety of King’s Batman concerns and is representative of the epistemology of Batman. Epistemology means:

[from Cambridge Online Dictionary]

epistemology definition: the part of philosophy that is about the study of how we know things.

Given the the strong Modernist elements as I perceive them in King’s Batman, it really does come off as the interesting Modernist trait of the unreliable narrator. That brings into focus how we know things – an epistemology. I regard everything (down to artist changes) represented in the as pertaining to the epistemology of Batman. It is truly fascinating and. Fucking. Brilliant. to have this tension between the unreliable narration of Batman with everything that is happening as being the epistemology of Batman (including Kiteman, and everyone/everything). It’s so fucking good, and it explains so much (including that line-up of everyone with Bane in #50: that scene represents the very epistemology of Batman, i.e. everything he knows).

Literary? Yes. Of merit? Fuck, yes. Eisner? Yep, hope so. I see elenents all similar in what I’ve seen of Heroes In Crisis. Looking forward to reading it.

There is no doubt that Tom King’s writings are stepped in bits of modernist, nihilistic, existentialist, and even absurdist philosophies. His basic themes are that the comic book medium is ridiculous, that human experience is defined by reaction to pain, that war is inevitable and pointless, that life is pointless except what you make of it, that suicide is a valid moral choice, and that there is comfort in repetition and patterns. Now are those 1) mainstream philosophies or 2) why anyone reads comic books? Probably not. Modernism and those other early 20th century philosophies were a result of the brutality and senseless of war – which clearly Tom believes as he alludes to in many interviews. He also thinks we live in an absurd time what with the Trump presidency and all, and he is quoted as saying that Mister Miracle was an attempt to show how someone could make sense of the absurdity. That book is textbook absurdism with Scott and Barda having family conversations during their endless war, the philosophical conversation while urinating on prisoners, Darkseid munching on carrots, Scott embracing the crazy fever dream of a life he has rather than fading back to “reality.” I even read an interview on the beginning of Omega Men, in which Tom King explains his use of several quotes about religion in that series. He says he grew up with parents of 2 different religions, but the quotes were ones he pulled from his mother’s book of quotes she kept on a bookshelf. He felt connected to her by these quotes since they had meant something to her. He doesn’t have invalid philosophies, just darker more depressing philosophies. And those don’t resonate with me at least, not beyond what I studied in high school English literature class. I can’t speak for anyone else.

The thing is, Nick, that there are no certain positions. What you describe as ‘depressing’, etc., etc., is not so. Not for me and not for many others. What would actually be depressing for me would be the highly rational prescription of what you regard as appropriate/good/fine. That would be SOOOOO depressing (and dystopic). Sooo fortunate that that is not the case.

I’m sweet with it all. I’m very selfish, and I like what I like. Including informed reading backed by millenia of critical theories. You don’t want to expand the way that you see things (and appreciate why Tom King maybe is an Eisner winning writer), I can’t do much for you.

You should know that every serious writer and critic has a solid foundation in the Classics to aid their own work. You’re free to appreciate and believe what you like. So do I have that freedom, and certainly not to bow to the concensus of someone that chooses ignorance of texts.

To quote one of the great literary critics, Dr Henry Jones Snr: ‘It tells me that goose-stepping morons like yourself should try reading books instead of burning them.’ Because surely not reading books (choosing/preferring not to recognise certain texts) is the same as burning them..?

Nice company you’re keeping with the alt-Right there. I was very impressed. Anymore proclamations of degenerate artists? (a Nazi term

This is the 3rd review I’ve read and I thought I was the only person who was mostly pleased with this series but I’m glad to know… I’m not alone. (Yeah, I went there.) But that last paragraph pretty much sums up my opinion on why I found this book so resonant. Great review.

I tried with this series, I really did, to find something to like about Tom King’s writing style. And at times, like certain instances with the therapy sessions, I did find things to admire about it. But more often enough, the book disappointed me. I’m not going to say it angered me, because I didn’t have that reaction (mostly because I’m not a huge Wally West fan).

It’s not that I can’t handle challenging material. I find history, psychology, political science and art fascinating. Those are subjects rife with challenging material for the human mind to chew on. My issues have more to do with his dialogue and character choices than his thematic elements.

There’s room for talking about depression and other forms of mental illness in a way that’s more than surface level in a comic book. I also appreciate his attempts to change how the story is told issue to issue (more of a thing in his Batman than HIC, but still appreciated nonetheless). As for his Batman, I think I have so many issues with it simply due to the fact that Batman’s the one character I’m most familiar with. I have a feeling that if I sat down and read Mr. Miracle I’d actually enjoy it, not having strong opinions about him as a character.

I read the final issue of this series, and amidst all the critical theorizing, I think that there was one technique that would have helped immensely. “Show, don’t tell.” For instance, we never did find out what Wally did to make amends or what he’d done that was “as good as what he’d done bad.” We got lots of dialogue but not much else–just a lot of confusing narration. See the timey wimey theorizing above.

There’s just no there there. If there is a solid message about healing and trauma, it was well concealed in this issue.

Hopefully, King can use this as a springboard for the Deep Meaningful Great Literature that he has in him and leave comics behind.

Comments are closed.