The internet has a tendency to ask questions it doesn’t expect or necessarily want answered. There’s an almost rhetorical nature to the way questions are posed. The question can then serve the dual purpose of both acknowledging and somehow dismissing the problem. As if by stating knowledge of the issue the author is absolved from rectifying a problem that can appear too large, too unwieldy to solve. Addressing the lack of diversity within the comic industry can often be seen as one of those problems. Creators Kelly Sue DeConnick (Bitch Planet, Pretty Deadly) and MariNaomi (Kiss & Tell, Turning Japanese) are no strangers to the excuses given for why the industry isn’t more diverse.

The work of DeConnick and MariNaomi often precedes them. They have solidified their position as barrier breakers and leaders in the industry. They aren’t resting on their laurels. Instead, they’re working to take away the easy excuse of not knowing where to find diverse creators. They’re creating resources to help people find and employ underrepresented creators in the comics industry.

“As a person of color and as someone who considers herself queer, I’ve been pretty marginalized myself, so it was nice to have a retort saying, “Oh yeah? There’s no people of color in comics?” and have a pretty firm place to direct someone who tells me that. I’ve heard that over and over. Just like I’ve heard, “There’s no women writers that are any good. Women aren’t funny.” We’ve just been told all this bullshit all our lives.” — MariNaomi

MariNaomi touches on the important element history plays in how people currently see (or perhaps choose not to see) marginalized creators. Historical accounts often erase the contributions and existence of people of color, women, and other voices. The names of women artists don’t easily fall out of our mouths. That’s not for a lack of women artists but rather because our historical record often overlooks their accomplishments. The art and comic space serve as fine examples of where women’s work has been overlooked or conveniently forgotten.

The early 1970s underground comix Tits & Clits, by Lyn Chevli and Joyce Farmer, was in part a response to the often conservative male-dominated industry. Tits & Clits was included in the underground comix anthology Wimmen’s Comix (1972-1992). The anthology provided a space to amplify the work of women creators while giving a good middle-finger to the Comics Code Authority (CCA).

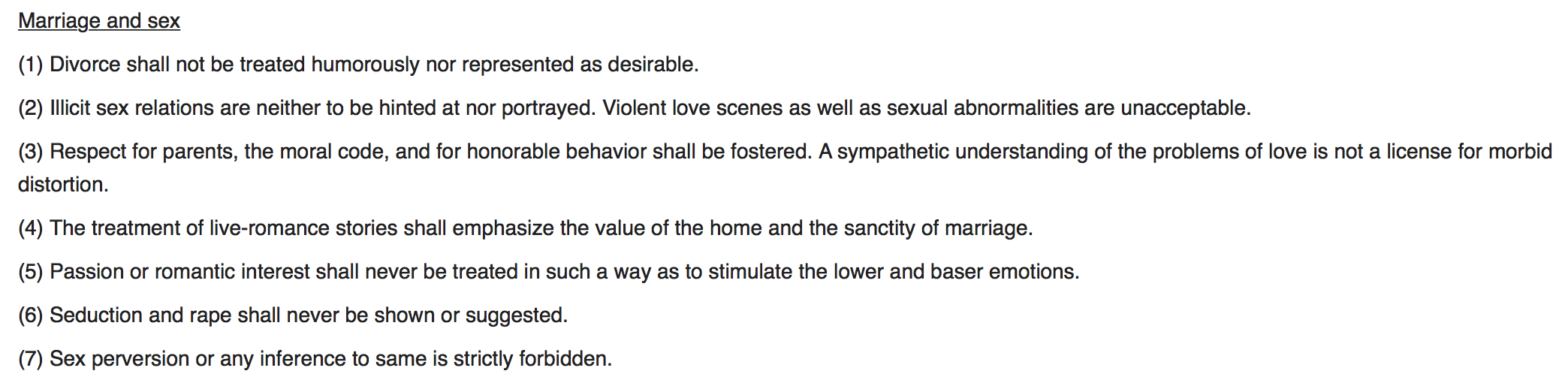

The restrictive code, adopted in 1954 by the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA), came from the warnings of psychologist Fredric Wertham. Wertham’s testimony before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary attributed crime and horror comics to juvenile delinquency and corruption of the mind. The CMAA adopted the code and began to self-regulate content in comics. Underground comix like Wimmen’s Comix, helped provide a much-needed platform to creators who were not only rejected by the comics establishment but felt unduly burdened by the restrictions placed on comics by the CCA.

The Comic Book Code all but guaranteed voices from diverse creators with different viewpoints would be shut out. There was no space for critical examinations of police brutality, crime, or discussions of the disparate policing practices of communities of color. The image below shows how depictions of law enforcement had to follow a very specific narrative.

#VisibleWomen will lead you to gorgeous art from women and non-binary comic artists. https://t.co/hIFkwC7Ind

— Twitter Moments (@TwitterMoments) August 7, 2017

On August 7, the hashtag event #VisibleWomen, organized by the production company Milkfed Criminal Masterminds, Inc., took over much of my Twitter feed. The event showcased women cartoonists, artists, colorists, letterers, inkers and writers. According to DeConnick, the Visible Women hashtag began spontaneously in March of 2016 following a week of colleagues asking her for suggestions of where to find women artists for hire.

While I was happy to do that and glad to be a resource, I also felt like, “You guys, there are so many.” […] I felt like they were out there but somehow invisible to hiring practices. So I used the hashtag VisibleWomen, which was a little bit tongue in cheek because of Sue Storm, and just made the offer that if any women comic book artists wanted to send me their links to their online portfolios, I would signal boost them. — Kelly Sue DeConnick

The hiring practices DeConnick cites aren’t about outright malicious attempts to keep women out of the industry. Instead, DeConnick says, it’s more complicated than that. DeConnick discussed the major publisher’s risk aversion as one such complication. While risk aversion is not unique to comics, it’s certainly played a role. “These are publicly owned companies, you don’t break talent heavily at that level. There’s a lot of pressure.” DeConnick went on to explain how hiring practices can end up perpetuating homogeneity, “you want to work with known talents and so it tends to be you’re working with the same guys, it’s usually guys, that you’ve always worked with.”

Kelly Sue understands the industry is still rife with misconceptions about what it means to be a women, “men are culturally allowed to be as different as their numbers.” To elaborate on Kelly’s point, men can be judged as individual comic artists, creators, illustrators, and writers. People don’t tend to look at the work of one man and make grand assumptions about all male comic book artists. Women are not afforded this same freedom. Women must continually confront the stereotype that their work will look or read the same. For DeConnick, that’s part of what has made #VisibleWomen so impactful to so many, “I think that’s maybe one of the coolest things about the Visible Women project is seeing the breadth of styles of all of the different artists.”

https://twitter.com/onelemonylime/status/894591107362942977

On Twitter, DeConnick announced any comics hiring professional could ask for a spreadsheet containing the names of those who submitted their portfolio to #VisibleWomen. DeConnick says they’ve used the spreadsheet internally to populate the Bitch Planet anthology. Following the most recent #VisibleWomen event, DeConnick says her team has been contacted by numerous hiring professionals, including book publishers on the hunt for illustrators. Wrapping up our conversation Kelly Sue was eager to direct me towards the work of MariNaomi, who’s been creating comics for over twenty-years. She’s seen where the industry has changed and where it hasn’t.

I think eventually we’ll realize, and what others of us have known all along, is in order to fairly judge or fairly create these characters and people, you’re going to have to hire people of color or whatever the marginalized people group that you’re trying to appeal to, you’re going to have to hire them on the higher level and give them some say in what’s happening. Not just draw your character a few shades browner. People will get it eventually. I don’t think that people, their hearts are in the wrong place. They just don’t understand. I’m hoping that little by little, that I’m helping. — MariNaomi

MariNaomi began the Queer Cartoonists Database and Cartoonists of Color Database in 2014 while doing research for Writing People of Color. She quickly noticed there wasn’t an easy way to locate creators of color or other voices mainstream comics usually leave out. She began crowdsourcing names and pretty soon had around 150 of them. MariNaomi told me creating the resources only made sense since she was the one with the information. Recently, both databases underwent a major redesign. MariNaomi and programmer Cameron Decker worked together to enhance the databases functionality, searchability, and design.

Maintaining a database is no small task. MariNaomi spends hours putting in each entry by hand. It’s a process she loathes for the monotony but loves because she gets to learn about each of these creators. Speaking with her, I sensed the deep connection she has to the more than 1500 names contained within these databases. There is an acute awareness of the hopes, dreams, and humanity behind each name.

There’s some amazing people out there. I feel lucky that I’m forced to interact with these databases every day because I get to see every single person who comes in and see how they’re growing and how much work they’re doing. –MariNaomi

As a casual observer of the #VisibleWomen hashtag, I was struck by the supportive and positive environment. I asked Kelly Sue how people can keep the sense of community associated with Visible Women alive. She said part of it is women having each other’s backs and supporting one another. DeConnick was quick to highlight who those women have been in her life, including but not limited to: G. Willow Wilson, Chelsea Cain, Emma Ríos, Marjorie Liu, Gail Simone, Kathryn Immonen, and Jen Van Meter.

Having colleagues that know your experience and share your ambitions and care about your craft, the way that the women I have mentioned do, it’s really important and I want the next generation of women comic creators coming up to have that, too. Have each others’ backs, find your girls. — Kelly Sue DeConnick

MariNaomi has a few simple wishes for the databases. She hopes to spread more awareness about the databases through word of mouth and social media. One day she hopes to hand over the reigns of the databases to a team with more resources, PR experience, and time. It was clear in talking to MariNaomi that she longs to see these databases grow and develop, but she is weary of the time and financial restrictions that often prevent this. She’s open to partnering with other like-minded people or organizations to make this possible. “One thing I’ve always wanted to add is a database of people who are disabled working in comics. I think that would be a really amazing thing to do. I would love for people to put something like that together.”

With these resources, Kelly Sue and MariNaomi hope to shine a light on the vibrant, active communities that already exist but also help those outside of these communities access creators who can help make comics a better, more inclusive place. Both are driven by a desire to do whatever they can, with whatever resources and time they have left over from their full-time jobs, to help push comics forward.

Databases Cited:

Cartoonists of Color

Queer Cartoonists

Additional Databases of Note:

Women Who Draw

Disabled Writers

If you’re a hiring professional interested in the creators who contributed their portfolio’s to the Visible Women event please email: [email protected]. The next Visible Women event is scheduled for February 2018.

You can read more about the work of MariNaomi on Patreon.

If you are creating resources for creators in the comics industry, let me know about them on Twitter @missafayres.

![[Above: Excerpt from the Comic Book Code of 1954. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency, Interim Report, 1955 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1955).]](https://www.comicsbeat.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Screen20Shot202017-08-1320at2010.01.2520AM.png.png)

Comments are closed.