The following year, the couple had their third child, Raphaël. He also suffered from lactic acidosis and died at 20 months. Heartbroken and desperate, Lavoie wanted to do something, anything, to help other parents facing similar ordeals. He launched a cycling event to fundraise to help fight lactic acidosis, which hadn’t received the attention required in research to efficiently combat. Over time, this has become one of the largest cycling events in the province of Quebec, has brought more awareness to the disease and has helped to kickstart the research on lactic acidosis. That’s where the story of Pierre Lavoie and Pascal Girard intersects. Lavoie lost two children to the disease and Pascal Girard lost a brother. Pascal’s parents knew Lavoie, which is briefly referenced in the book when, after receiving a phone call, Pascal’s mother (off-panel) says to her husband that Pierre’s daughter passed away. A harrowing reminder of the pain of losing a child.

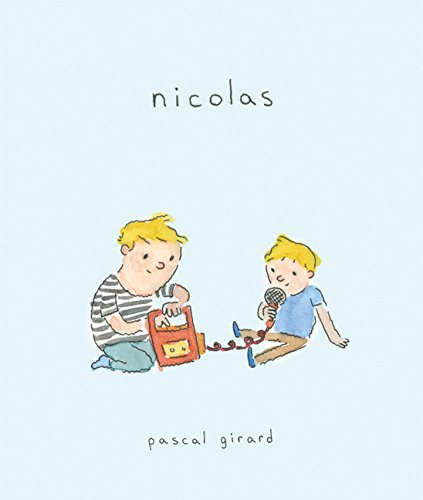

When we asked Pascal about his creative process, he mentioned the same thing one can find in the book’s introduction; he wrote the original version in a small sketchbook, during a weekend, directly in ink without a script or pencils. This seemed quite unusual from the way we heard Pascal works nowadays. We had heard before our meeting that Pascal now works in a different method, using moving panels so he can modify the pages as he sees fit. Knowing this now actually helped us unlock some discussion on his previous book, Petty Theft, in which we noted certain pages ended at random places before starting new scenes. He was sliding panels, adding and removing when necessary to make each sequence work better. It was a fascinating discovery really. For the newest edition of Nicolas, Pascal went back to the original method he used back in 2006 (sketchbook, no script). The original version of Nicolas was done very differently from how Pascal works now, but he managed to go back to his old style for the afterword. It was an artistic challenge for him since his methods have evolved over the past 10 years. Revisiting Nicolas some ten years after it came out was an interesting choice for Pascal. A way to bring more awareness to his early work, but also to showcase how far he’d progressed artistically. His lines are clearer, thinner, more in control than they were back then. The CBC Books website has a great image comparison of the two works that can be seen in more details here

In meeting Pascal, we were faced with a conundrum. How do you ask questions on a book that contains so many painful memories of loss? We skirted around this at first, but Pascal was quick to let us know that he was open to our questions. We began by asking about the surprising absence of Pascal’s parents from the book. We noticed that while the first half of the book is focused on the life of Pascal and the second half focused on his relationship with his younger brother Joel, the book never shows his parents. They’re present, but mostly in the background. Part of this comes from a respect for his parents’ private lives. In many ways, they’ve been through a lot and revisiting these emotions didn’t feel like something he wanted to subject them to. Nicolas is then an exploration of the artist’s relationship with loss and his younger brother Joel and not an exploration of family. That distinction became clearer in the second half of the book. On the same subject, he also mentioned that Lewis Trondheim provided him with feedback on his earlier book Petty Theft to the effect that his point of view was limiting his story potential. He said that it would have been nice to develop the character of the book thief a little bit more. By only exploring his version of events, he refrains from providing a complete portrait of his situation. Nuances are missing as we only get the narrow view of the artist. It doesn’t take away from the strength of Girard’s book and Nicolas in particular, it is a deeply personal and honest work, but by refraining from showing his parents we miss out on some potential understanding of the situation. Still, a few of us thought that the absence of his parents had its own weight and implications.

This personal story enriched our understanding of Petty Theft, a book we read two years ago. There is an underlying fear of parenthood in Petty Theft and while the story didn’t feature Pascal as the main protagonist, it shows an ambivalence to parenthood and children. Perhaps a fear of loss motivates this fear of parenthood. There is a risk in having children, of feeling unconditional love for someone, and knowing that there’s the possibility that something might happen to them. Losing a child to a car accident or having them suffer from a genetic disease are possibilities that are too painful to consider. For someone who has witnessed their parents experience this pain, it is understandable that they might avoid parenthood altogether. There is no way to tell, but it was an interesting avenue to discuss.

There was a wonderful moment during our discussion where, after pointing out that the book’s timeline starts compact but takes increasingly more time between each story, Pascal mentioned that grief eventually fades away, but is never completely gone. Grief returns every once in awhile, at various moments. It’s in the very nature of moving on that we will sometimes unexpectedly be reminded of an event or a memory. One such memory seemed to have motivated Pascal’s decision to base the second part of Nicolas on the complicated relationship between him and his other brother, Joel, rather than on the loss of Nicolas. To show that there is something after loss and grief, that you can move on, that you can build around the void left by the loss of a loved one.

By the end of our discussion with Pascal, we had gained a very thorough understanding of Nicolas. A short work but a very dense multilayered comic. Regardless of how well we understood the book, there were a lot of elements to unpack and, even after an hour and half discussion, we still felt like we didn’t dig as deep as we could. The honesty and frankness of the story is quite moving. We couldn’t recommend it more highly. There are so many layers of emotions that one can’t help but feel satisfied after reading it.

The Ottawa Comic Book Book Club is a small group of comic enthusiasts meeting monthly in Ottawa.