Yesterday, the annual Comic Arts Brooklyn festival presented a series of panels hosted by a set of visionary cartoonists. Of particular note was a panel entitled “Childhood,” where Maus cartoonist Art Spiegelman and Toon Books founder Françoise Mouly paid tribute to the comics that inspired them as children. Focused on Winsor McCay‘s Little Nemo in Slumberland and the works of French cartoonist Fred, the couple gave a talk that sought to track comics’ progression from its “low” status as a form of children’s entertainment to its present status as an emergent form of genteel high art.

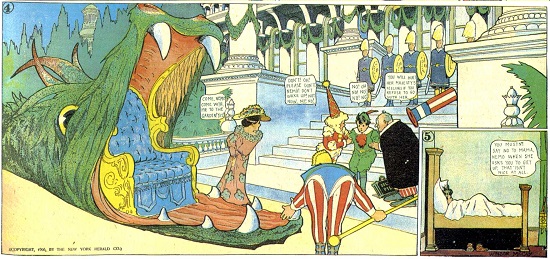

According to Spiegelman, comic strips were originally “showcases of color for newspapers.” Color printing, which had become more accessible at the start of the 20th century, opened up endless new possibilities for creative expression in mass media, and comics like Little Nemo were some of the first to take advantage of the process. According to Mouly, the practice as applied to comics generated excitement for the first color films.

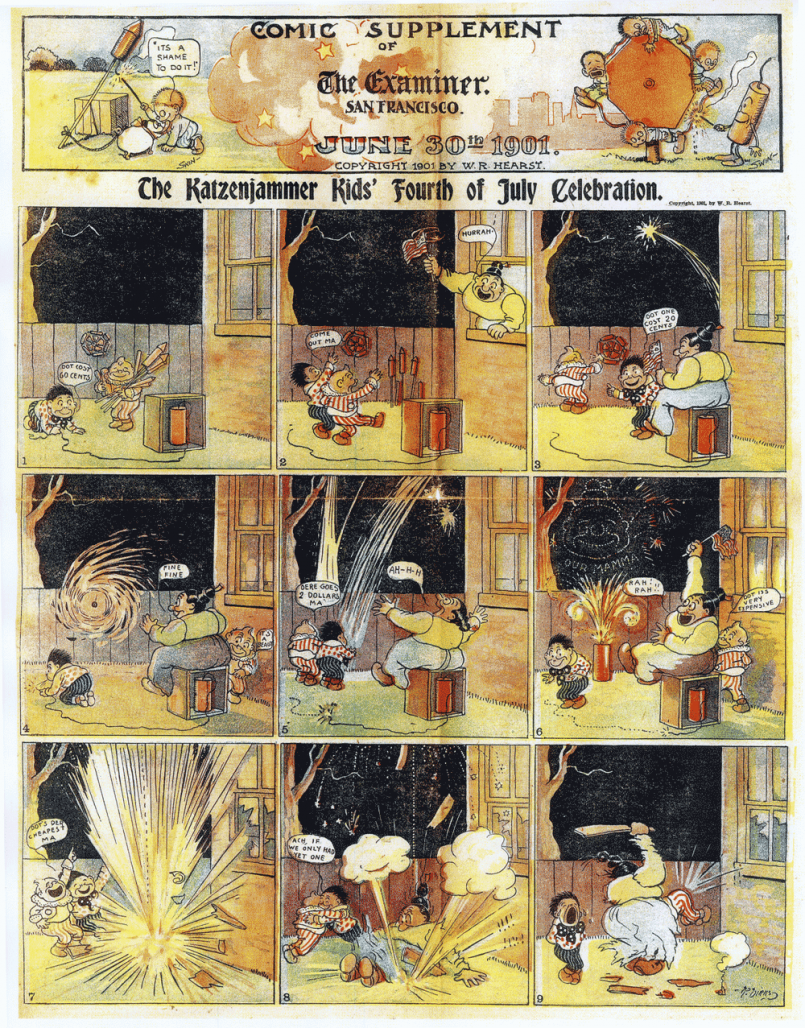

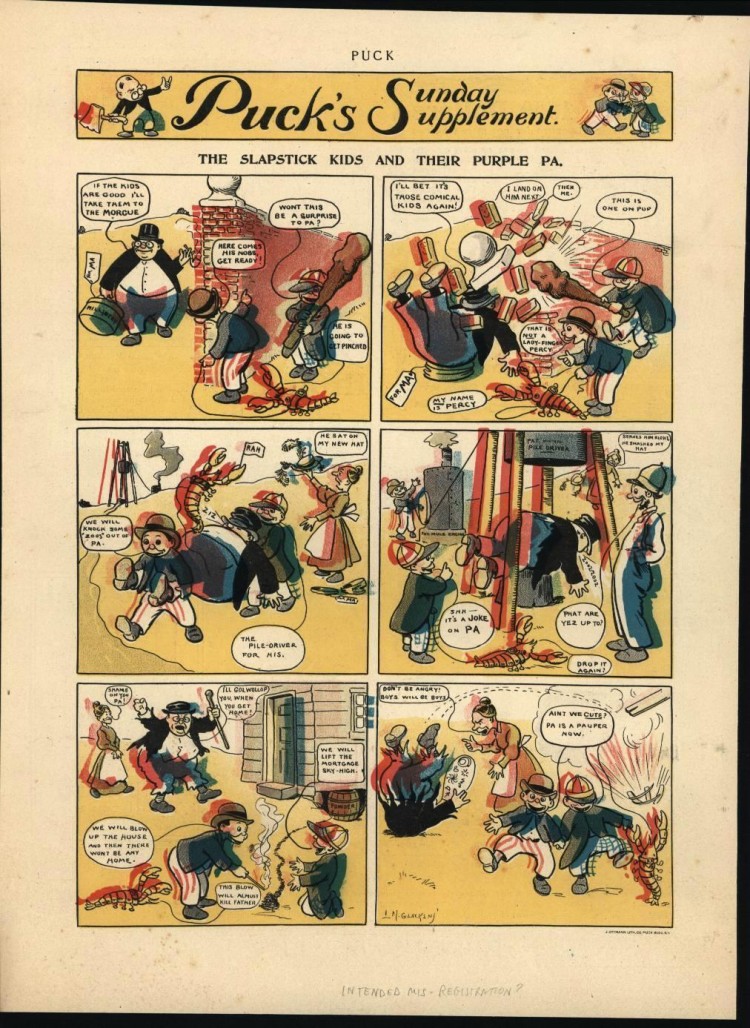

Many of the original “Sunday funnies” were intentionally base in their humor, appealing to childrens’ mischievous streaks and rampant desires for humor. Spiegelman pointed towards The Katzenjammer Kids as a prime example of this devil-may-care attitude in early comics. Created by Rudolph Dirks and drawn by Harold H. Knerr from 1912-1949, the series focuses on two young brothers in their perpetual battle against authority in all its forms, parental and otherwise. The strip was widely successful, and attracted attention from Puck, America’s first successful satirical magazine. In a Puck strip called The Slapstick Kids and their Purple Pa drawn by L.M. Glackens, the cartoonist parodies the strip, intentionally distorting the color printing to exaggerate the original comic’s unrefined sensibilities. According to the panelists, this was an example of “high art and low art in direct collision.” Spiegelman quipped that comics “were not what Sundays were intended for.”

From there, comics began a process of gentrification. Little Nemo was characterized by the couple as a prime example of this phenomenon, with McCay demonstrating many new techniques that would revolutionize the medium and are still employed by cartoonists today. Of particular note was McCay’s visual representation of the passage of time in several Little Nemo strips.

Another, more negative example of gentrification in comics was suggested by Spiegelman, who said the gradual transition from the carefree Yellow Kid comics to Buster Brown morality tales was a transition from “yellow to shit.” These more innocent comics would serve as voluntary precursors to the comics that followed psychologist Fredrick Wertham‘s persecution of the comics industry in 1954’s Seduction of the Innocent, a book that argued that comics were responsible for a moral decline in American youth, encouraging children towards a life of deviance and violence. The book’s publication resulted in comic burnings and the creation of the Comics Code Authority, which limited creativity and marginalized the industry for nearly a half century following its creation.

Two years before Seduction of the Innocent, however, MAD Magazine was conceived. The couple pointed at its publication as comics’ loss of innocence, where childish mischief gave way to truly “adult” oriented content. MAD informed the creation of Spiegelman’s and Mouly’s Raw, a carefully curated underground comix magazine that the couple characterized as a weird intersection– genteel compared to comics, but vulgar compared to regular fine art.

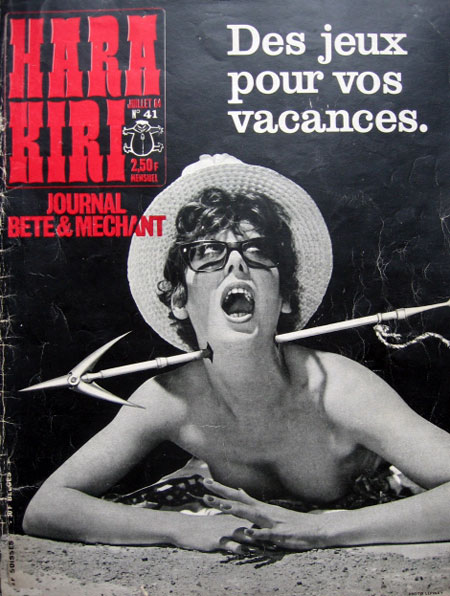

Another magazine that toed the line between vulgar and refined was Hara-Kiri, co-created by French cartoonist Fred. Most famous for his work on Philémon, the cartoonist worked with humorist Georges Bernier and journalist François Cavanna to create an anti-authoritarian and satirical publication dedicated to pointing out social wrongs and political corruption. Emphasizing their mission statement, the magazine bore the subtitle “Journal bête et méchant,” which translates to “stupid and vicious magazine.” Hara-Kiri is notable to Spiegelman and Mouly because of its role in the feminist movement. Many of the magazine’s covers feature women reclaiming their bodies through acts of physical mutilation.

The couple closed their informative panel with a look at Mouly’s Toon Books publishing imprint, which was created after Spiegelman and herself noticed a distinct lack of modern comics being clearly marketed towards children. Cast Away on the Letter A: A Philemon Adventure is a new translation of one of Fred’s classic stories and Little Nemo’s Big New Dreams is a compact and affordable edition of Locust Moon’s Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream, an oversized book featuring modern day Nemo stories by prolific contributors including J.H. Williams III and Cliff Chang. Spiegelman and Mouly paid special thanks to Woody Gelman, a 20th century cartoonist and publisher who released the first collected edition of Little Nemo stories and, according to Spiegelman, is responsible for rescuing the original art after he discovered the strips were being used as coffee coasters (!).

Thanks for the nice coverage, Alexander! Two things, though: I think you mean “genteel” in your headline, although the early newspaper strip artists were certainly Gentiles, as well. And the French cartoonist Francoise spoke of is merely “Fred”–Philemon is his character.

Thank you again for coming, and for the report!

Shows how much a Violet education has done for me, huh? Maybe I should have gone to school uptown. ;)

Thank you for the pointers and for all your hard work on the panels this weekend. It was wonderful, and I’m glad I was able to attend!

Comments are closed.