Photography by Gabriel Serrano Denis, unless otherwise noted

“The next level is ownership.” This was Dawud Anyabwile’s response to an audience question asked in the closing minutes of the “Hip Hop in 3D” panel which took place at the Schomberg Center’s 8th annual Black Comic Book Festival, which took place on January 17-18, 2020. It was a powerful statement that gave the panel’s audience a well-intentioned hit of knowledge and insight that is sure to stay with them for a long time.

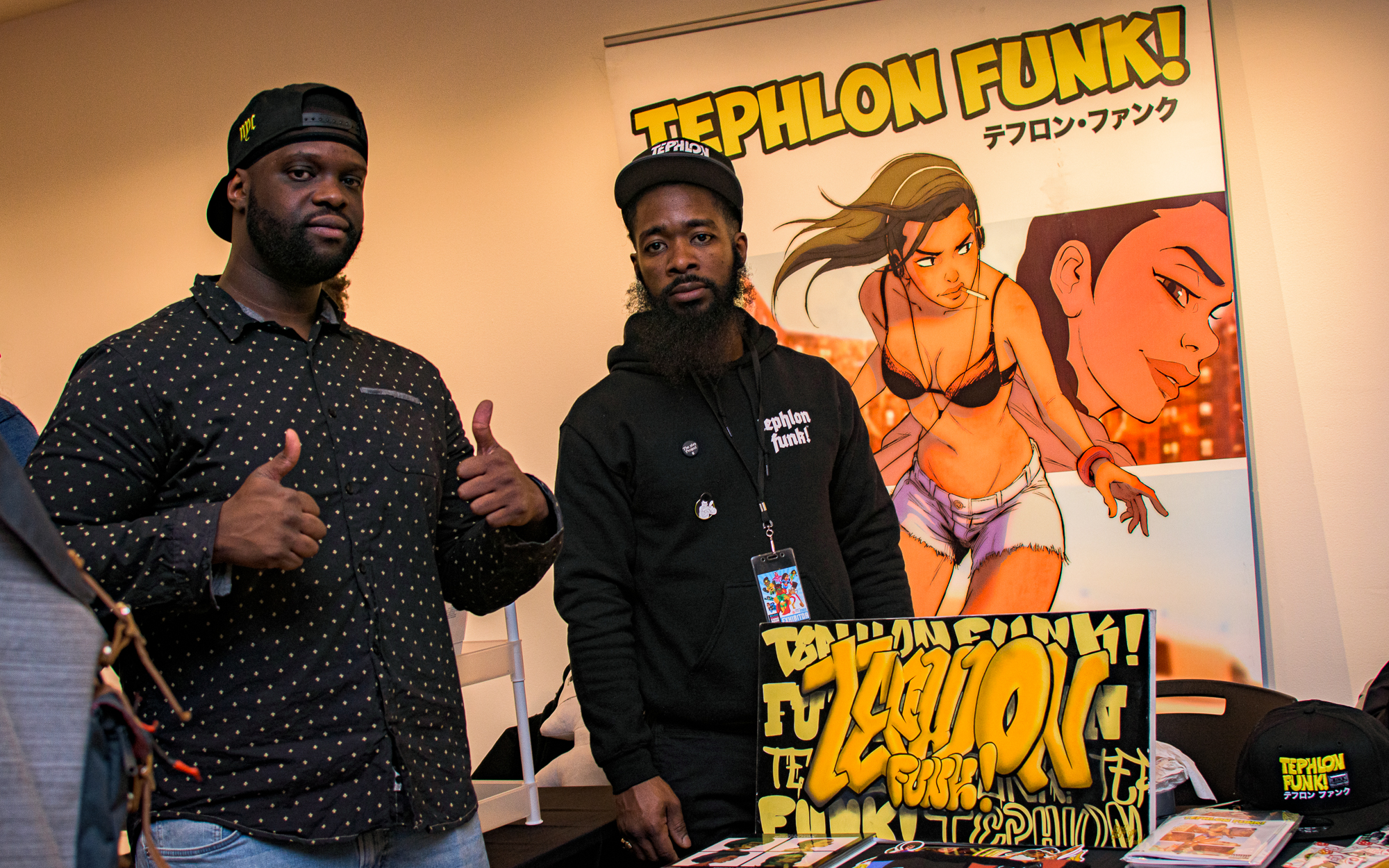

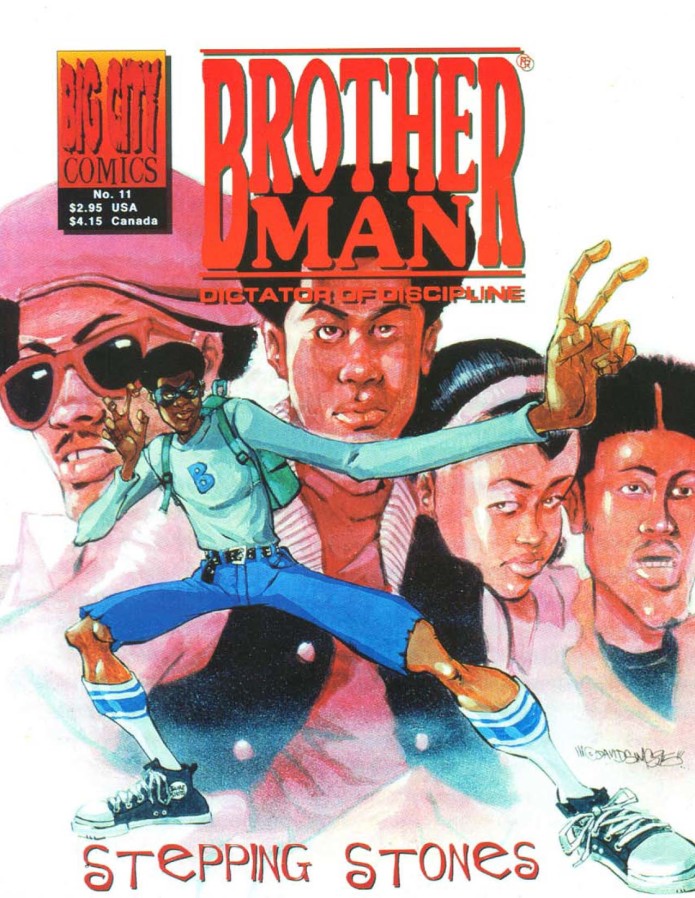

Dawud is the artist and co-creator of Brotherman, a black superhero/vigilante that fights criminals looking to maintain the tradition of oppression that keeps black communities poor and underdeveloped. Knowing the kind of power that comes with owning his own character, which was co-created with author Guy A. Sims, is what led him to remind everyone why ownership is so crucial in black comic book storytelling. It speaks to truth and representation, something the Black Comic Book Festival has been preaching for eight years now with growing intensity and clarity.

This year’s edition—opening 2020 with a healthy dose of hope for more black representation and visibility in comics—managed to feel bigger despite occupying the same amount of physical space the Schomburg provided last year, which is limited and requires careful organization (which the organizers achieved for the most part).

While the festival was crowded and mobility somewhat difficult, the cues for the panels were designated to another location and it did allow for a steadier flow of traffic. There is one reality, however, the festival must contend with every year: the Schomburg isn’t getting any bigger. The fact more people want to be a part of it each year is another worry because of space. Thing is, the Schomburg is deeply ingrained into the event’s identity. They’re inseparable.

The Schomburg is the place for the Black Comic Book Festival, no questions asked. Should it ever be moved to another venue, one risks losing some of the magic in the transition. Perhaps transformed is a better way of putting it, but there will be a change in the feel of it should it come to pass. Not that this has been a rumor of some kind or even discussed, to the best of my knowledge.

People braved a snowstorm and harsh temperatures to attend the festival, keeping a busy show floor at all hours of the day. Peak time was from opening to closing. All this goes to show just how important this event is to the community. It’s unmissable. It is, and has been for some time now, a cultural tradition. It is New York culture. Harlem culture. Black culture.

This was my third time visiting the festival and can honestly say it still provides one of the most authentic and unique comics experiences in what’s a heavily overcrowded convention field. A lot of it comes down to the festival owning its identity and being aware of the expectations and responsibilities it has to meet, which is why I believe the panel offering has been so compelling and forward-thinking year after year.

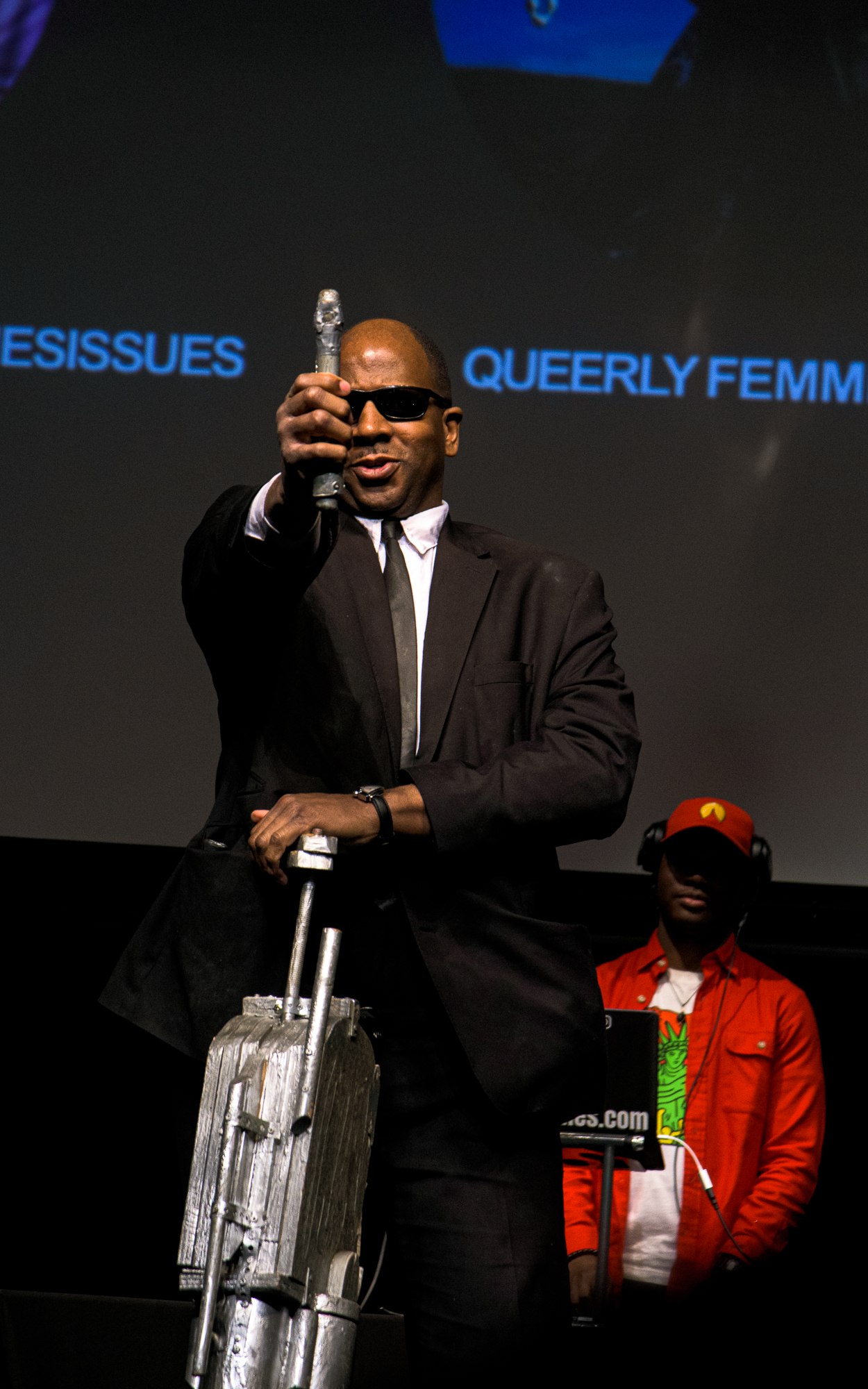

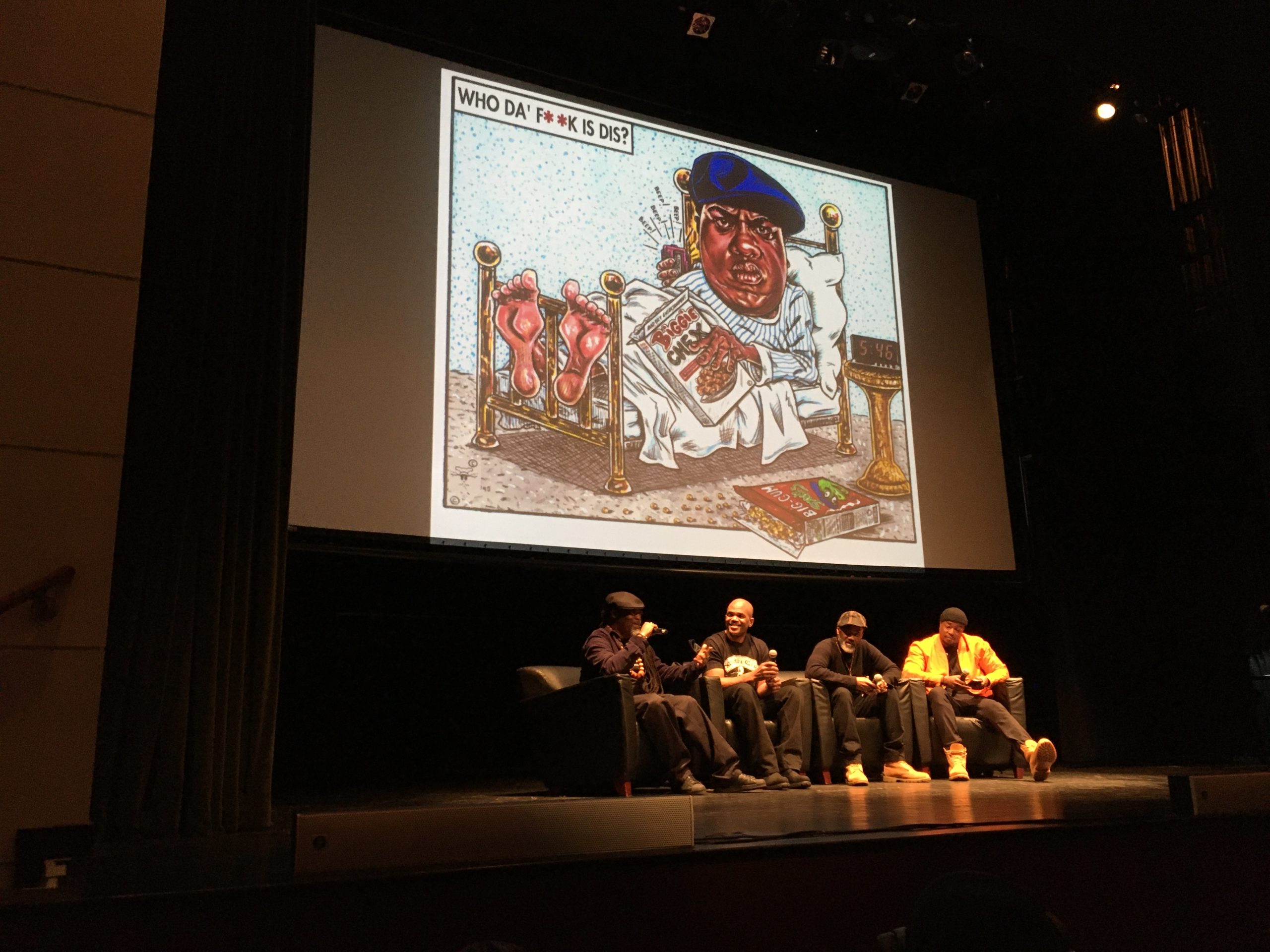

The aforementioned “Hip Hop in 3D” panel was a highlight. Darryl ‘DMC’ McDaniels (DMC: Darryl Makes Comics), Andre Leroy Davis (known for “The Last Word” column from The Source magazine), and Dawud Anyabwile (Brotherman) spoke to the role and responsibility black creators assume when creating comics in a culture that to this day struggles with creating all-black ensembles at the mainstream level.

Davis, for instance, told a story about how working as a freelance artist came with the anxiety and tension of having to present a body of work that showed he could draw white characters. This is despite carrying a portfolio largely comprised of white characters with only a sprinkling of black character designs in it. After seeing how certain publishers fixated on the black designs and questioned his ability to draw white characters, Davis decided to fill his portfolio with black characters only as a challenge to interested parties.

Anyabwile added to Davis’ point by stating that this worry over something being too black was difficult to argue as legitimate. He said, “if you put on a blindfold and walk into a comic store, you’ll pick up a comic that’ll satisfy you if white characters is what you want.” The same can’t be said of black comics, he suggested.

McDaniels, on the other hand, focused on how comics offered him a template to use when approaching Hip Hop. He said, “When you look at the flawed guy that becomes a superhero, we relate. When that flawed guy becomes superheroic, he becomes something bigger. He tells us we can become that thing as well. That’s how I saw it with Hip Hop. When I’m off-stage I’m Darryl McDaniels, but when I’m up there I’m DMC. I become super. Comics gave us that template. That’s how powerful they are.”

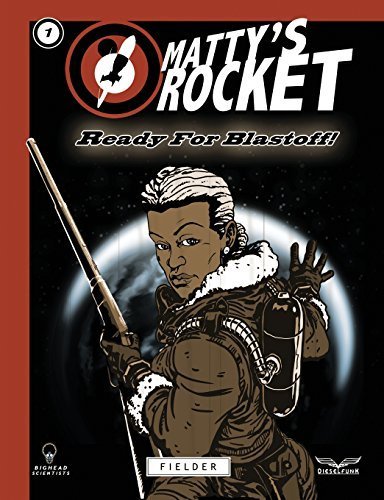

These types of perspectives elevated the discourse of comic book representation and made it all the more crucial. It can mean so many different things to many different people. Tim Fielder (Matty’s Rocket), for instance, spoke about how afro-futurism can extend beyond sci-fi, challenge it even, to acquire even more complex voices in a panel called “Epic Narratives in Comics: Sci-Fi, Afro-Futurism, and Beyond”

According to Fielder, afro-futurism comes down to a powerful rejection of certain narratives. Of black characters looking to the future to change it in any way, shape, or form within their power. He offered some interesting examples of this: “Thomas Molineaux was like the first black athlete and he beat his way to freedom. He was a fighter and he beat up so many people competitively that he earned his freedom. He fought professionally. So that’s an afro-futurist…Barack Obama went crazy and thought he could be president, and he did! He’s an afro-futurist. Afro-futurism can extend to politics. It can extend to law. And it can extend to comics.”

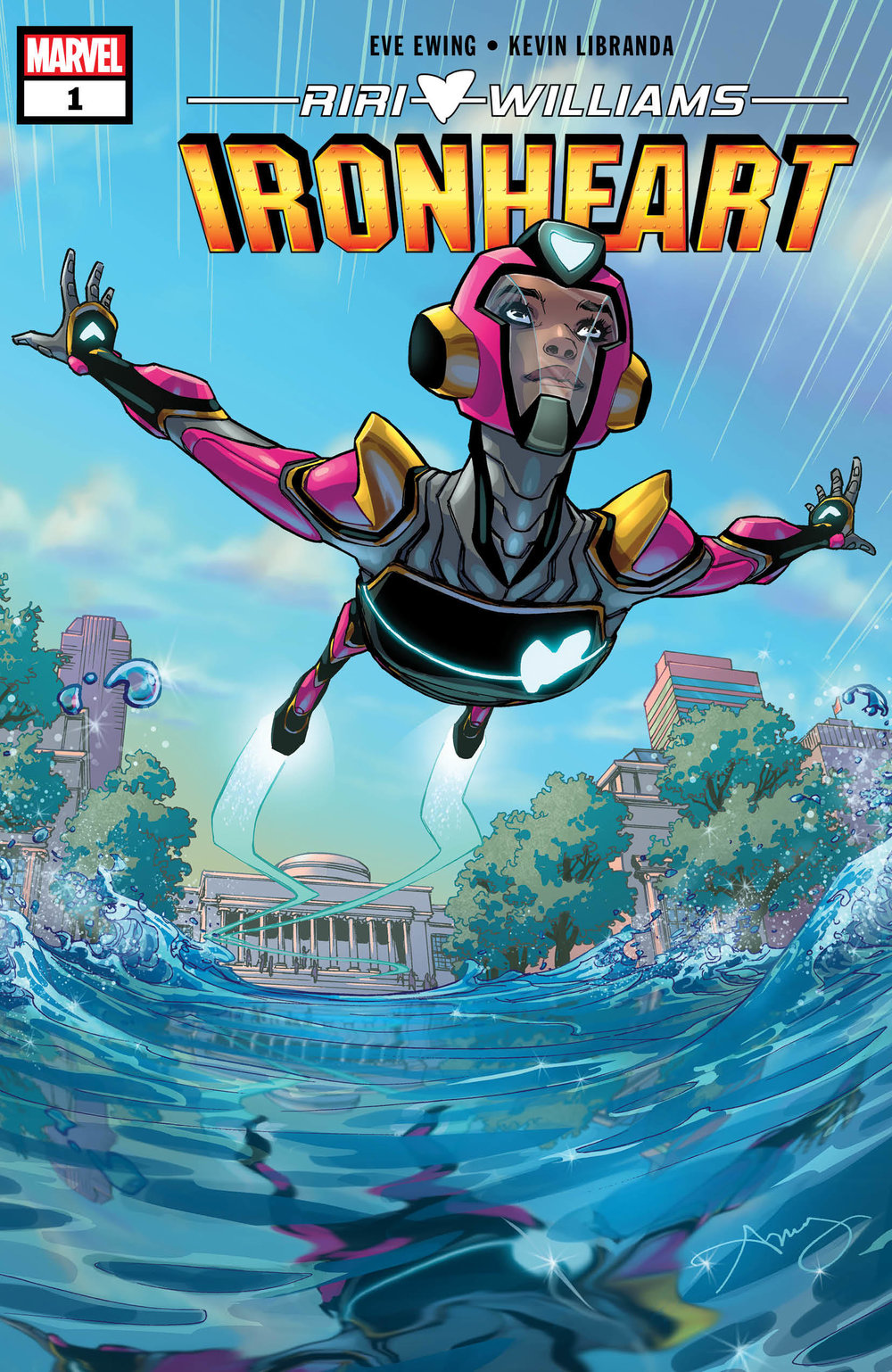

Along those same lines (in terms of looking beyond genre limits), Eve L. Ewing spoke about the representation of black misery in fiction, in a panel called “#StrongFemaleLead,” and how we can go beyond that while still owning the reality of the black experience in America.

On a question asked by moderator Janicia Francis concerning pop culture’s insistence on recurring to images of violence against black people to get a point across about life as a black person by way of shock (something Francis calls ‘black misery entertainment’ or ‘black misery media’), Ewing said, “I think that the entire history of black art is a double helix of joy and misery. That’s what it means to make black art in the United States. I don’t think images of black people being hurt, graphic images of us dying, necessarily makes someone be less racist. It’s not enough to change people’s minds if they don’t love us.”

The depth and the strength of the Black Comic Book Festival’s panel programming is almost without rival, as I’ve tried to show with these panel snippets. What’s an uncomfortable topic in a ‘wider-audience’ convention is necessary discourse here. It’s one of the aspects that makes this festival such an important cultural event.

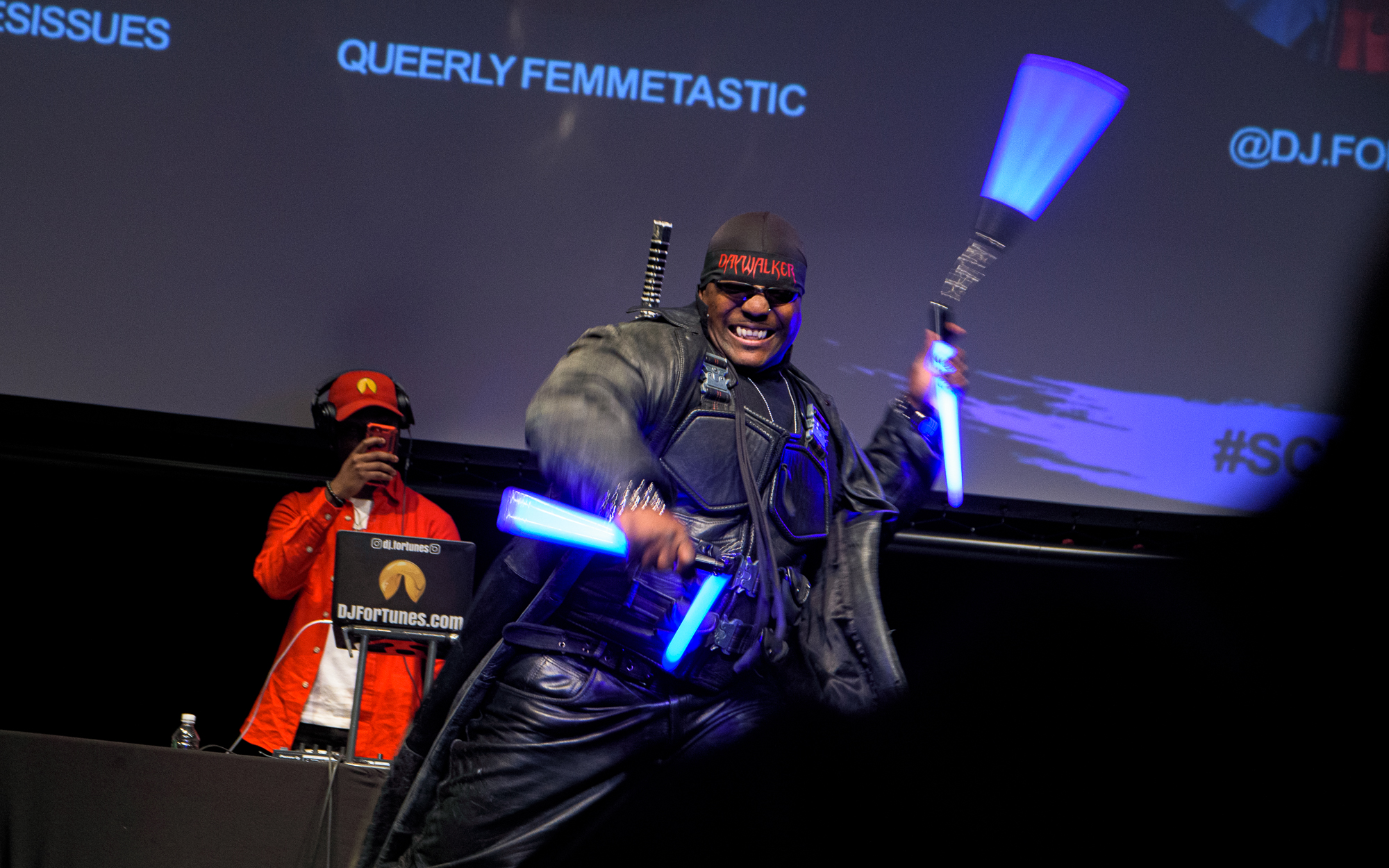

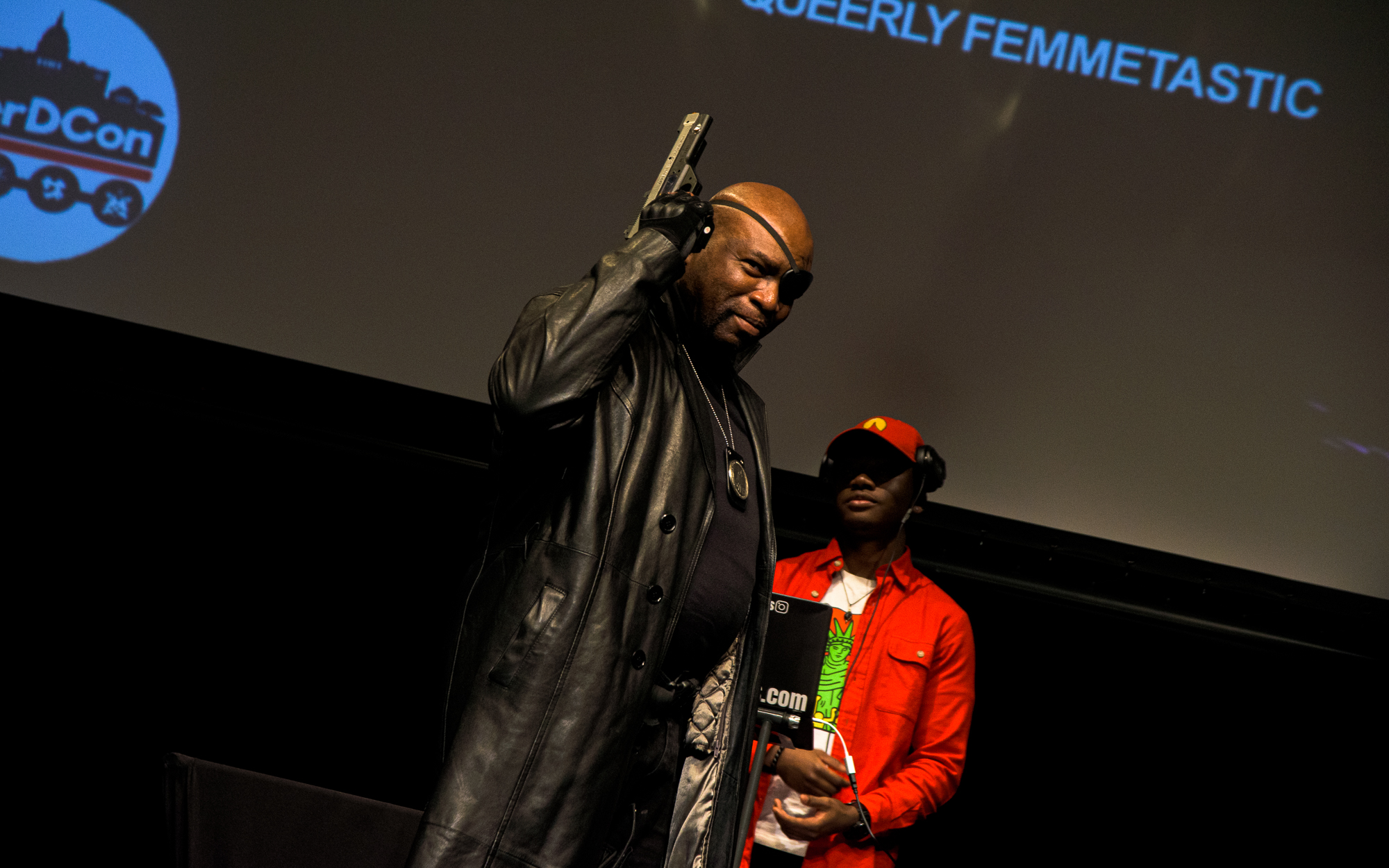

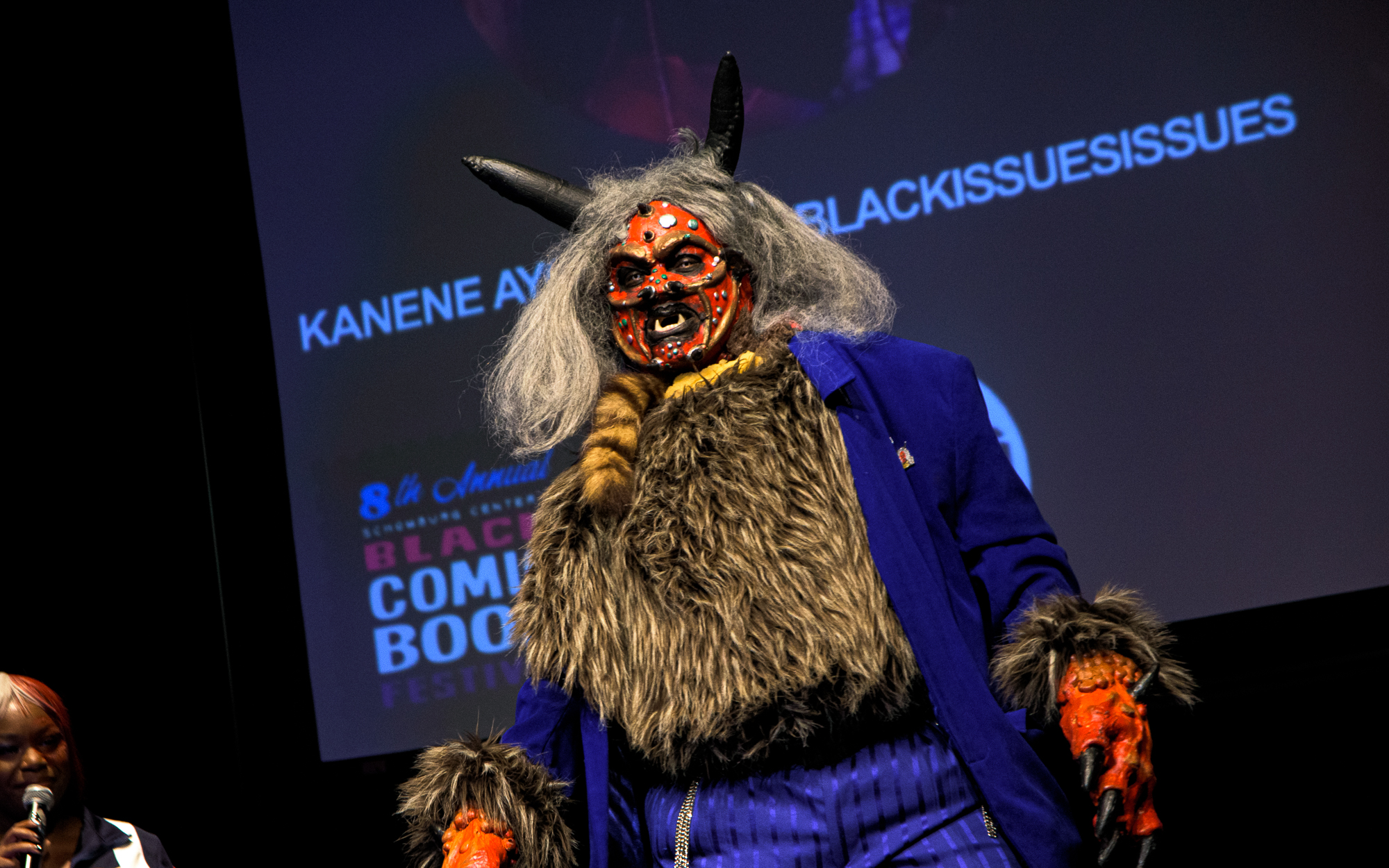

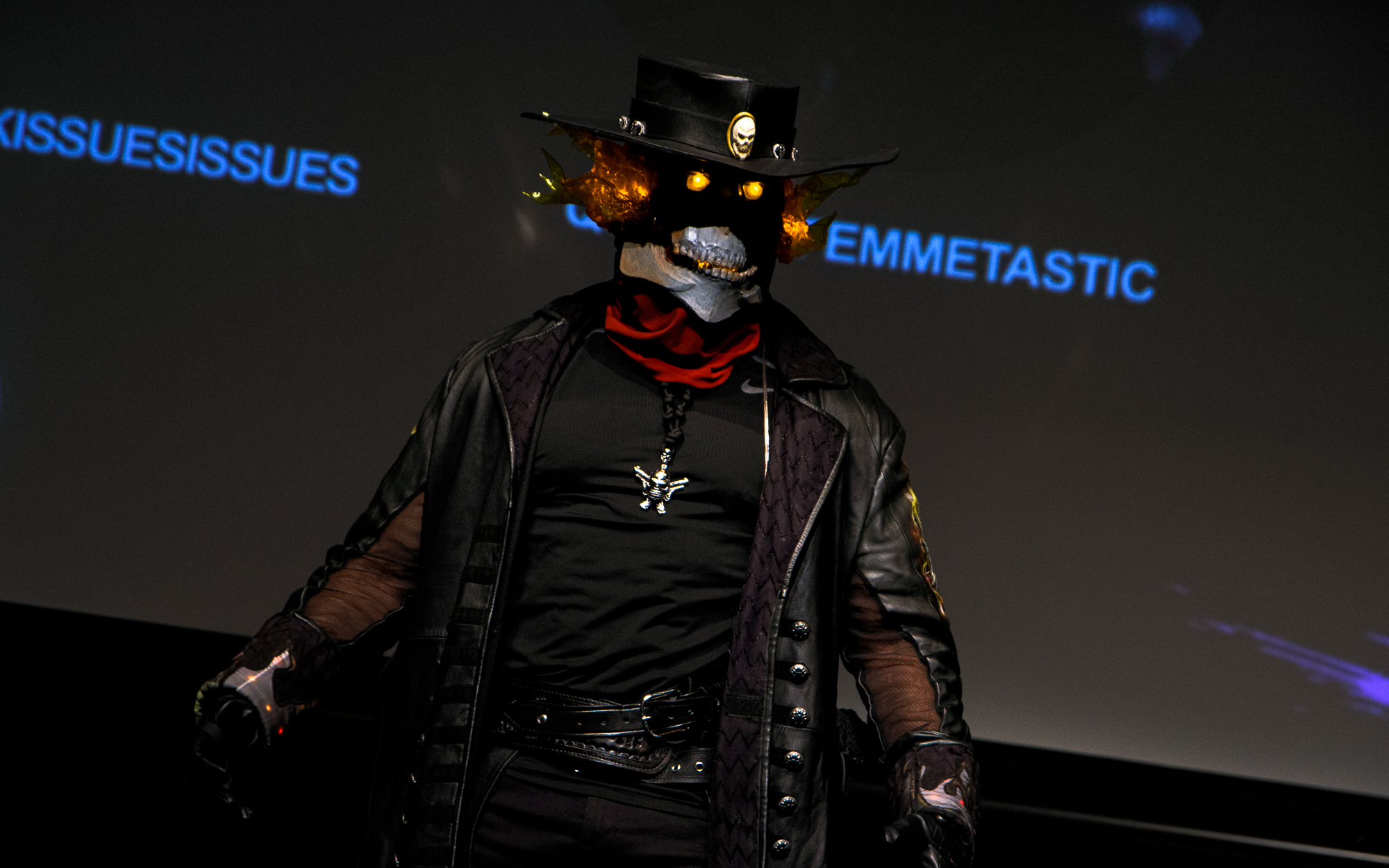

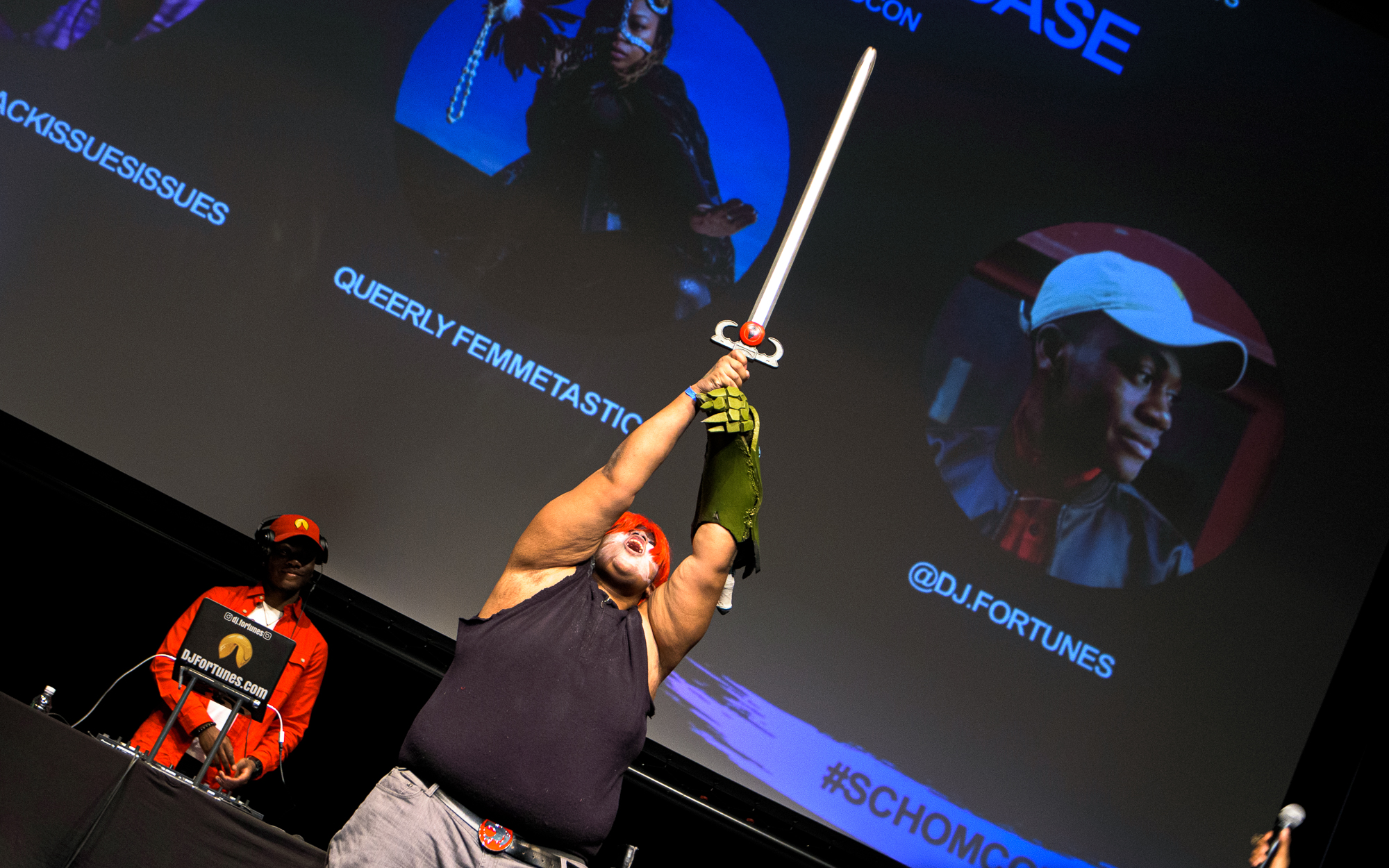

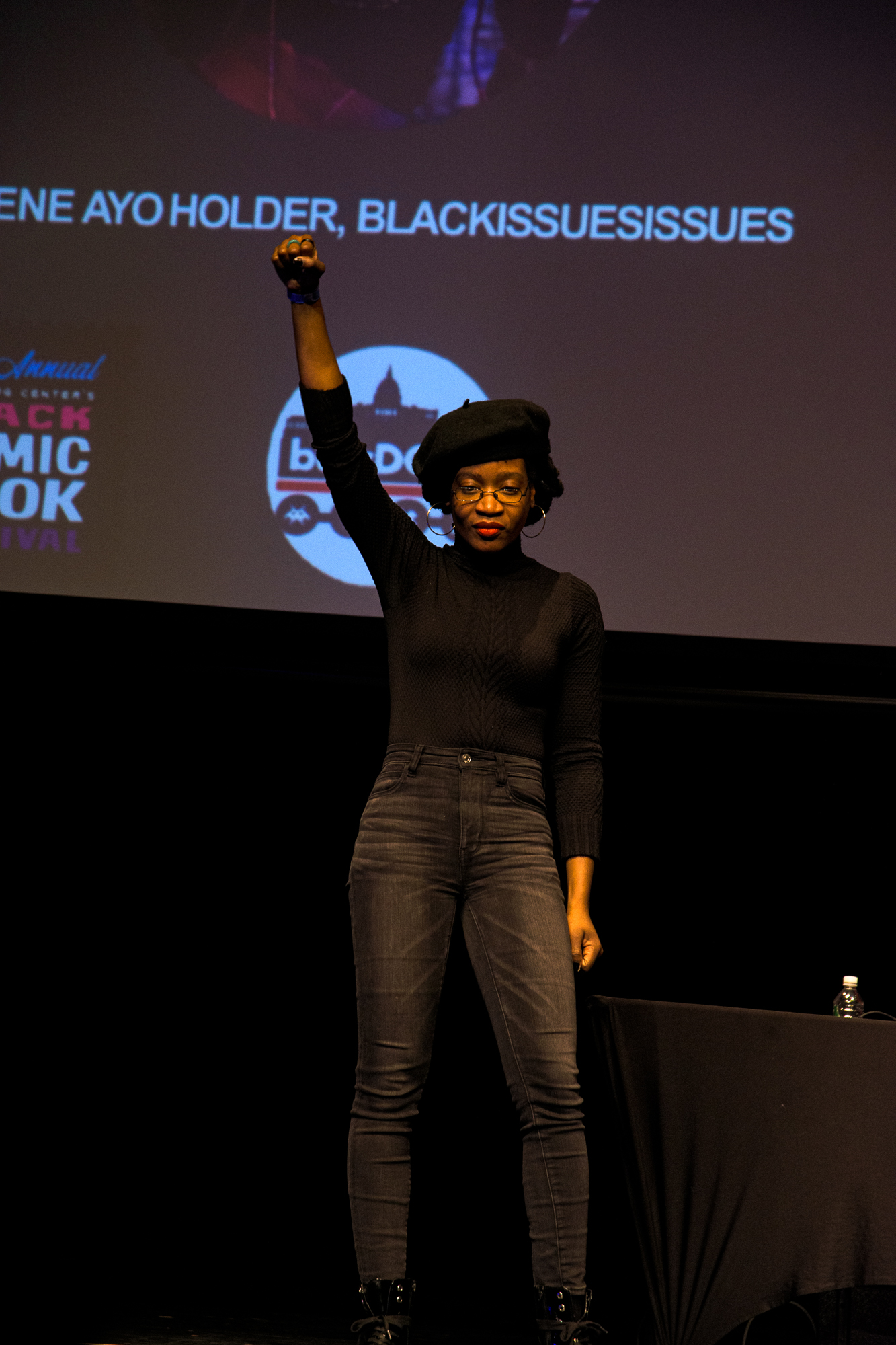

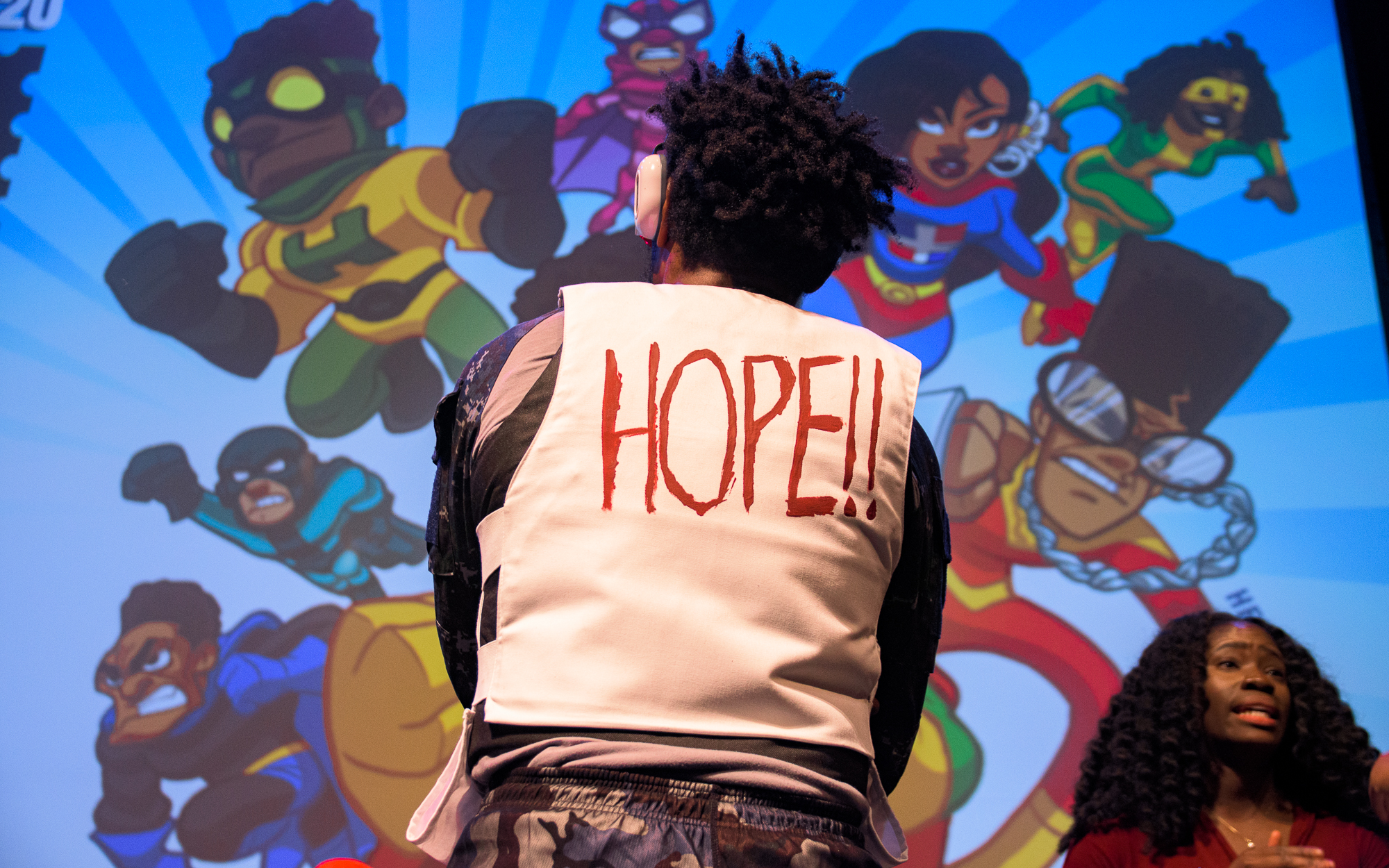

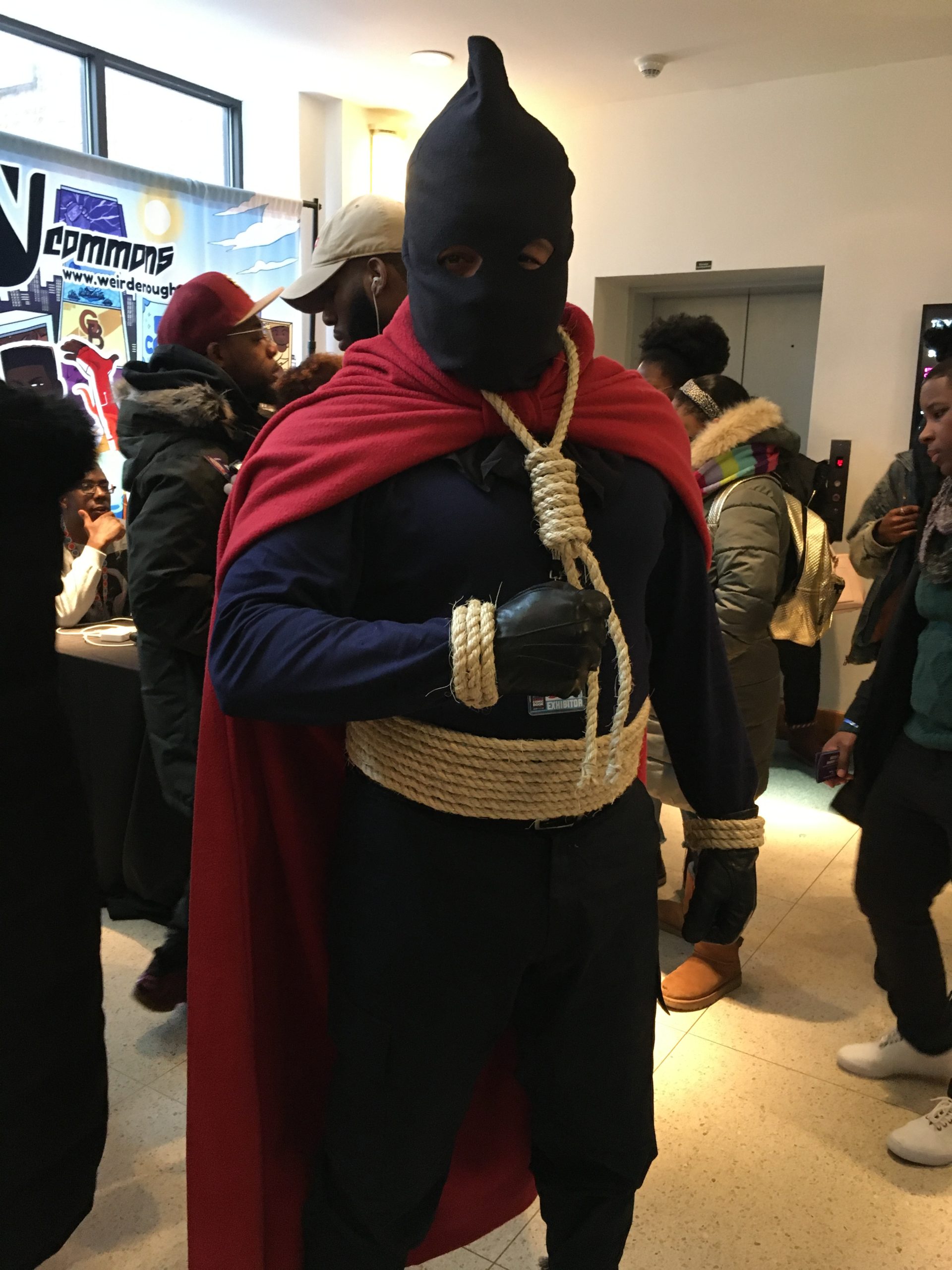

Finally, the festival had another great cosplay showcase with variations on established characters made to reflect and celebrate blackness. From medieval female versions of Nick Fury to Black Lightning the showcase was a blast that also reflected that idea of ownership I’ve been mentioning throughout the article.

One cosplayer quite simply went as a Black Panther activist, doing Wakanda Forever signs and Black Power signs. The history that was honored and referenced and celebrated in this festival, just on the cosplay front alone, is a testament to the reach and impact of this event. It explains why it’s so successful and so anticipated.

I’m already excited for the 9th edition of the festival and have no doubt it will create new narratives and new philosophies, even, as creators look to a future that is black and beautiful and, most importantly, owned by the black community.

Here’s an image gallery showing some of the best cosplays from the showcase: