Reading comic book scripts is notoriously tedious, and it’s easy to understand why. They’re generally only read by a handful of people, most often the artist, letterer, and the editor. A comic book script isn’t not written to be enjoyed, it’s written to be understood.

A comic book script is, for all intents and purposes, an instruction manual from the writer to the rest of the creative team. Some back and forth can and should occur after the writer sends out the script, but that doesn’t prevent the average script from being a slog to read. Why, then, are scripts in other storytelling mediums so often entertaining? How can writers adapt their comic book scripts to be similarly engaging? This piece attempts to answer all of that and more.

I sometimes prefer reading a script for a movie, television series, or play to consuming the work itself. That’s because they’re not written like a series of instructions, they’re written to be stories that are entertaining in their own right. Their authors know their scripts will be read by dozens to hundreds of people, and they wanted to impress the executives, actors, and crew members attached to the project. Case in point: the script for the Harry Potter and the Cursed Child play sold millions of copies because playwrights are taught to write scripts compelling for a wider audience

What makes scripts for other mediums different from comic book scripts? They cut out a lot of the fat. A film script doesn’t explain everything the audience will see in the final cut of the film, because those decisions belong to the director and background details might change over the course of the movie’s production.

Scripts for movies, television, and theater are largely comprised of dialogue with minimal direction and description. Which makes sense, since dialogue is the most exciting component of nearly any script. When description is required, sentences are kept short and snappy.

Comic book scripts need to follow the same principles. Dialogue and captions are more compelling than descriptions of what the artist is to draw. A writer needs to keep and panel descriptions concise whenever possible. However, more description is always needed for a comic book than for other art forms. Because of that, the description itself needs to grab readers.

Editors often explain how dull it generally is to read a script, which is one reason they prefer to read a finished comic to evaluate a writer’s work. But editors frequently single out Fred Van Lente for his ability to make his comic book scripts entertaining. That’s one of the many reasons he’s written comics for every publisher you can think of. If you make an editor’s job more enjoyable, they will naturally be more inclined to hire you.

Van Lente is widely respected for his understanding of the process of creating comics. He co-wrote Making Comics Like the Pros, a guidebook published by Random House that’s a must-read for aspiring creators. He also shared how he formats his scripts, and his template has been widely adopted by other comic book writers. His style of writing scripts, however, has not.

Up-and-coming comic book writers will only improve their odds by writing scripts others will actually enjoy reading. To make it easier for others to replicate the readability of Van Lente’s scripts, let’s examine a few things he does so differently and effectively.

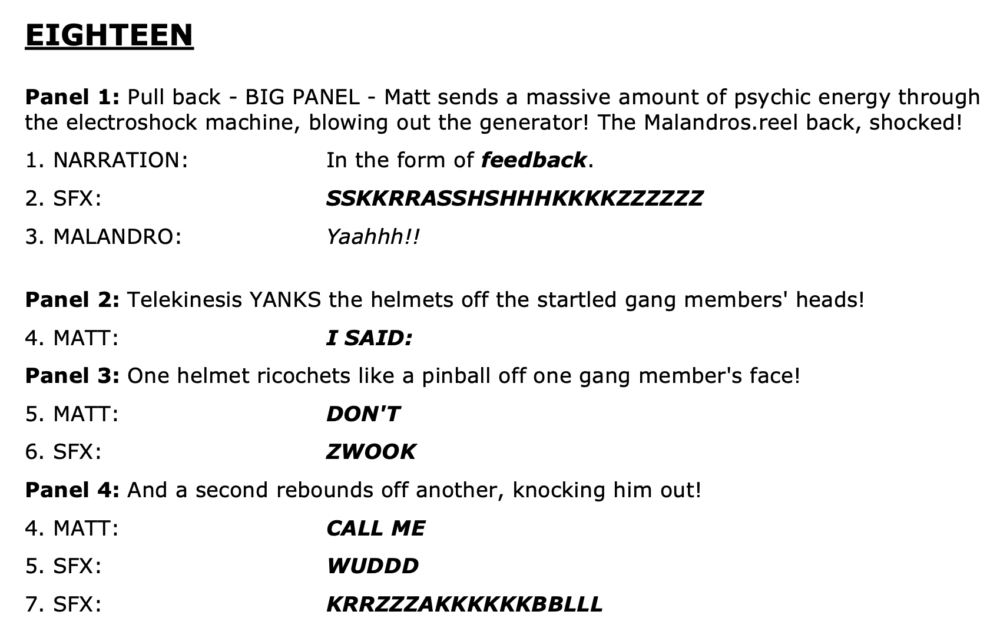

The first thing you’ll notice reading Fred Van Lente’s scripts is that they feel conversational, like a story he’s telling to entertain friends. See this excerpt from the script for Brain Boy:

The exclamation points and words in all caps clearly illustrate how excited Van Lente is about the page, and that enthusiasm is infectious.

Details

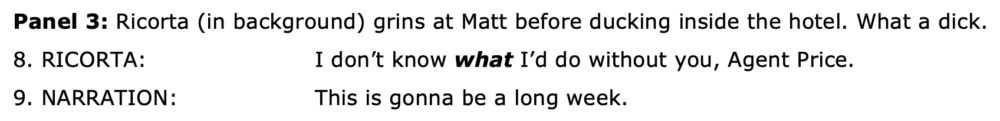

Some writers try to keep panel descriptions succinct, believing brevity is the soul of wit. But that philosophy doesn’t necessarily apply in a comic book script. You can see that Van Lente includes “unnecessary” details in his scripts.

“What a dick” may seem superfluous, but it adds personality to the script and keeps readers entertained.

Lastly, Van Lente seamlessly bakes visual references into his scripts.

Most comic book scripts include images as reference for the artist. Usually, though, writers will completely interrupt the flow of their scripts in order to nail down exactly what they’re looking for at the sacrifice of the reading experience. Better to be light on details within the script and elaborate through other forms of correspondence.

Van Lente finds various opportunities, like the ones listed above, to liven up his comic book scripts. He remembers that even the artist drawing the comic down doesn’t want an instruction manual, they want a story. He perfectly straddles the line between explaining and entertaining. Other writers should learn to do the same.

More engaging scripts don’t just impress editors, they result in better comics. When a script is written well enough to evoke a certain mood, the artist better understands what the writer has in mind and can more accurately capture that on to the page.

Just as importantly, well-written scripts excite collaborators about bringing the writer’s words to life as full-fledged comics. Crafting a more engaging script is a valuable opportunity for any writer to improve the experience of their collaborators.

Making Comics is a monthly column about the process of creating sequential art.