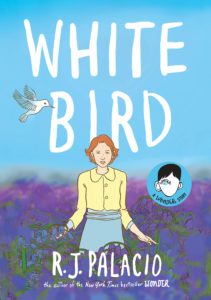

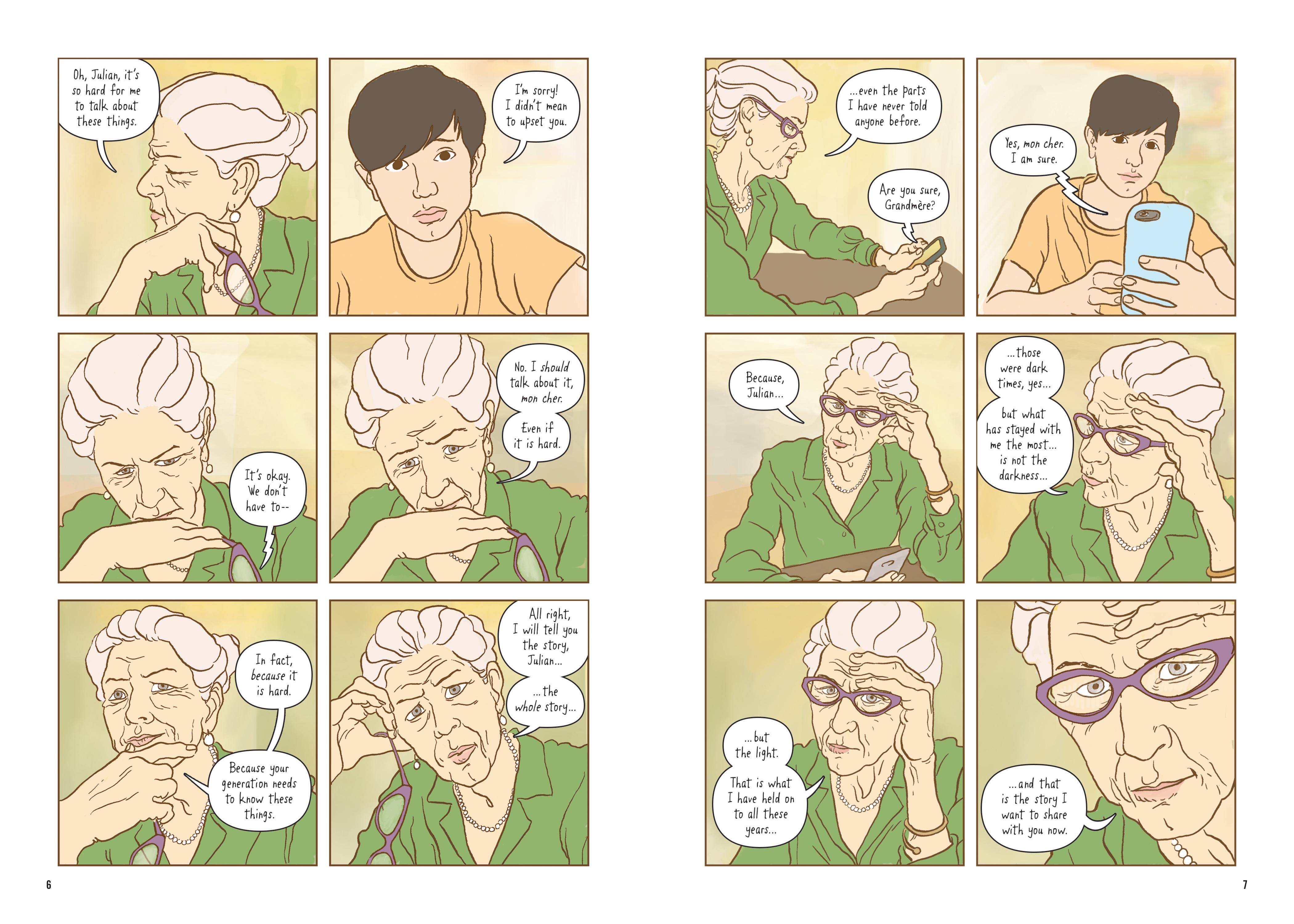

It is said that trauma can linger through the generations. As a society, we haven’t been the most adept at understanding the long-term effects of coping with the consequences of trauma. Indeed, in many ways, our reluctance to comprehend the magnitude of the past ensures that progress occurs only at a glacial pace. Yet, there are always signs of hope. People are resilient and brave souls prevail against heavy darkness. R.J. Palacio‘s new original graphic novel, White Bird (Alfred A. Knopf Books), is a testament to the capabilities of people to survive against the worst excesses of bigotry and baseless hatred.

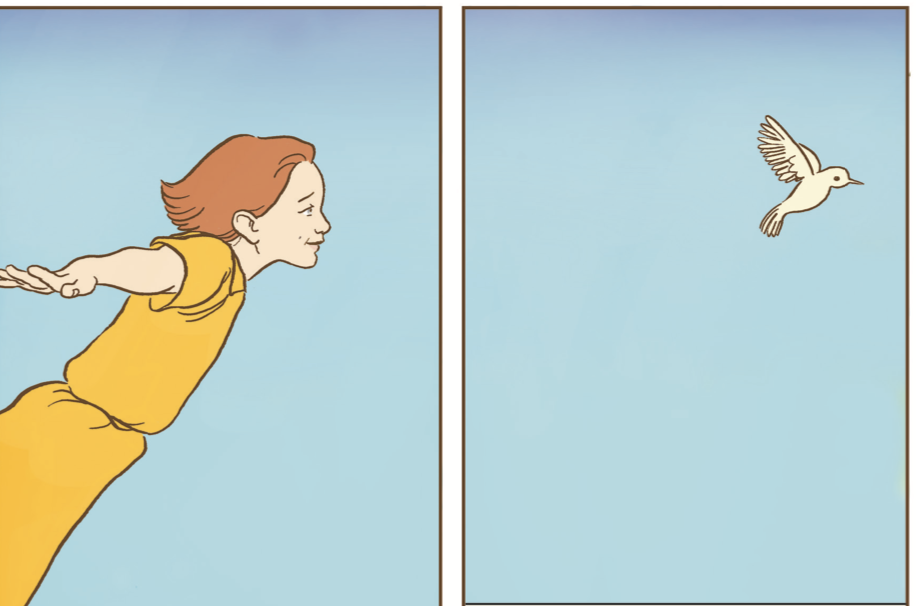

Palacio, the author of the New York Times best-selling middle-grade novel Wonder, posits White Bird as a book of historical fiction as well as a reflection of where we are now at this critical contemporary moment. Focusing on the teen years of Sara Blum, the book shows the arc of how Nazis stripped Sara of her rights as a citizen and as a student, but how they could never take away her dignity and desire to yearn for a better world.

While the comic takes place in France during the Holocaust, it is natural to spot the parallels to what is happening now: the separation of families, ideology replacing compassion, and the pockets of resistance standing bravely against an uncaring, nationalistic fervor. Before the book’s debut at New York Comic Con next week, I had the chance to chat with Palacio about the process of writing White Bird, approaching the Holocaust with care, and why history is such a powerful mirror to the present.

R.J. PALACIO: t’s a pleasure speaking with you, too!

FROST: I wanted to start by asking about the particular circumstances that influenced the creation of this book. In the back matter, you mention that White Bird is your “act of resistance for these times.” When did the idea for the book come to mind, and when did you start putting pen to paper?

PALACIO: I had been working on another novel—about halfway through, in fact—when the November 2016 elections happened. And I found that I could no longer do what I needed to do to keep writing it. I couldn’t disengage from the world the way I needed to. I couldn’t not be actively attuned to the disastrous events happening around me, whether it was the rise of white supremacism in our country, targeted discrimination against the LGBTQ community, systematic separation of families on our borders, which seems to me to be a crime against humanity, or any of the other affronts being mainstreamed by this administration.

So I put my novel away and decided to write White Bird, a story that suddenly seemed very relevant to the times we’re in. The fact that I would be drawing it instead of just writing it meant that I could engage with the world the way I needed to. I could still watch the evening news while drawing on my iPad, for instance. So choosing this topic to write about at this time was my way to be useful, to use my soapbox to draw parallels, and hopefully inspire young readers to make connections between the past and the present themselves, and do what they need to do to ensure the past doesn’t repeat itself.

FROST: Though White Bird is historical fiction, it contains many elements of truth. As a storyteller, what rules did you give yourself while writing the book that would make all the elements feel authentic, while still being free to create a semi-fictional narrative?

PALACIO: The first mandate when approaching historical fiction: do the research. I spent many months reading, researching, immersing myself in the time period. While fiction allows you to bend your story to suit your vision, it doesn’t allow you to bend the facts of the larger story in which your smaller story is set—if it’s historic. The past is unalterable, absolute, so you can people it with make-believe characters, but you can’t change it.

FROST: There are countless Holocaust stories—nonfiction, fiction, and everything in between—on bookshelves now. What inspired you to add your own story to the robust selection of Holocaust and World War II-related literature? Who exactly is your audience?

PALACIO: There are many stories out there, for sure, but fewer than you might think for children ages eight to twelve. In fact, there are a lot of kids in this country who don’t know anything about the Holocaust, or only learn about it in seventh or eighth grade, when their teachers have them read The Diary of Anne Frank—if even then. Two-thirds of American millennials have never heard of Auschwitz. There are a couple of reasons for that. One I kind of get, though I don’t agree with it, and that’s the impulse parents have to shield their children from some of the harsher realities of the world. Certainly, the fact that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust is almost impossible to comprehend, and even harder to try to explain to children. It’s horrific and tragic, and almost too sad for words. So I think parents try to shield their kids from the entire subject because it’s so difficult to talk about.

Having said that, we’re not doing our kids any favors by not telling them about this time period in an age-appropriate way. Because while what happened in the Holocaust exposes the very worst of humanity, it also speaks to the resilience of humanity. People—not enough, but some—survived those horrors. People—not enough, but some—risked everything to fight those horrors. Kids can learn from that. I know I have. The other reason kids don’t know about this time, though, is not because their parents are actively shielding them from knowing, but because it’s so removed from the everyday lives of their families or communities that they don’t think it relates to them. So it’s not a question of these kids being shielded from the truth. It’s a question of these kids being deprived of it.

FROST: When it comes to stories about the Holocaust, there’s always a delicate line to tread. What research did you do to ensure that what you wrote not only felt visceral but aligned closely with historical events?

PALACIO: Long before White Bird, my husband and I did a deep dive into his family’s history, specifically as it related to his mother’s family in Poland. My husband’s grandparents lost everybody in the Holocaust—their parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins. Everyone. That kind of loss sears itself not only on the generation experiencing it, but on subsequent generations. It becomes part of the fabric of their existence. So when I started writing White Bird, I couldn’t help but have my mother-in-law front and center in my mind. If you want to talk about a visceral connection, that was it for me.

As for the historical events, it all comes down to the research, and as I mentioned, I did a lot of it. I read countless books and articles about the Holocaust, specifically as it related to France, and about the Vichy government, the Milice, the French Resistance, the Righteous Among Nations, the villages that hid Jews, the complicity of some, the outrage of others. There is so much primary-source material available, which was especially important because not only did I have to write the details accurately, but I had to draw them accurately, too. I had to draw the right fonts in newspaper headlines, and the types of airplanes that were used to bomb the mountains where the Maquis were mounting a resistance. I had to find period-appropriate clothing for the models who were my photographic references. I had to research what a French barn looked like, and what kind of scooter a little girl would have ridden, and what her backpack might have looked like, and the size of the buttons on her dress.

I had to do all this research because I wrote the story of Sara within the scope of the historical events, which needed more than a bare-bones idea of events as they unfolded when I started writing. It helped that I had lived in Paris for a year, so I was already somewhat familiar with aspects of the larger story. But once I started doing research, I often found that historical events helped my story, rather than hampering it. Sometimes I wrote a scene, or had something happen that maybe I wasn’t sure could have happened, only to find out from my research that there was a similar story that did happen. Sara hiding in a barn, her school being raided, her mother being removed from her home by gendarmes even though she was a naturalized French citizen and lived in the “Free” zone—these were things that I wrote first, only to find out from further research that they did happen to real people.

FROST: In the notes, you write that while your husband is Jewish, you are not. In this era where representation and identity are so closely tied in popular media, culture, and the arts, did you feel an extra burden for White Bird to be read as a more universal book than one specifically about the Holocaust? In other words, though the protagonist of White Bird is Sara Blum and we see her struggles against anti-Semitism and fascism through the lens of the Holocaust, can White Bird be read more broadly as a call for action against reactionary hate?

FROST: Not to give too much away, but I wanted to mention an aspect of the book that I thought was remarkable. Though much of the narrative takes place in the past, there is a framing story that takes place in the present. And in those present-day sections, you connect the actions of Holocaust to what is happening now with regard to the plight of asylum seekers and refugees. Do you see a direct connection between the suffering that happened then to the suffering happening now?

PALACIO: Thank you for pointing that out, because that’s very much what I wanted to convey: the relevance of Sara’s story to the world today. To me, the story of a young girl who is being persecuted in her own country, who is threatened with deportation, who is targeted and stripped of her human rights because of her religion or cultural heritage, is also the story of immigrant children across this country, and refugees and asylum seekers around the world. There is a dearth of compassion in a great number of people in the world right now, fueled by xenophobia and lies, enabled by ignorance of the past, that can only be combatted by the will of millions of people who seek to fill that void with something else, something better. Those voices will win in the end—it’s just a question of how many people have to suffer until they do. As a writer, as an artist, I feel obligated to use my platform to raise awareness, educate, perhaps even inspire, to mitigate the harm as much as possible until the world comes to its senses.

White Bird hits shelves October 1 from Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers. Palacio will be present at this year’s New York Comic Con on the “Sharing One’s Truths: Non-fiction, Memoir, Historical Fiction, and More” panel on Thursday, October 3, Room 1A18 beginning at 4 p.m. You can also follow Palacio on Twitter. This interview is dedicated in the memory of Esther and Hariska (Fanny) Scherzer.