The new DC miniseries Gotham City: Year One from superstar lineup Tom King, Phil Hester, Eric Gapstur, Jordie Bellaire, and Clayton Cowles shines a spotlight on an important (and problematic) character from the earliest days of comics: Slam Bradley. But who is Slam — really — and why is he such a difficult character? And do his secret origins — never before revealed! — contain some clues?

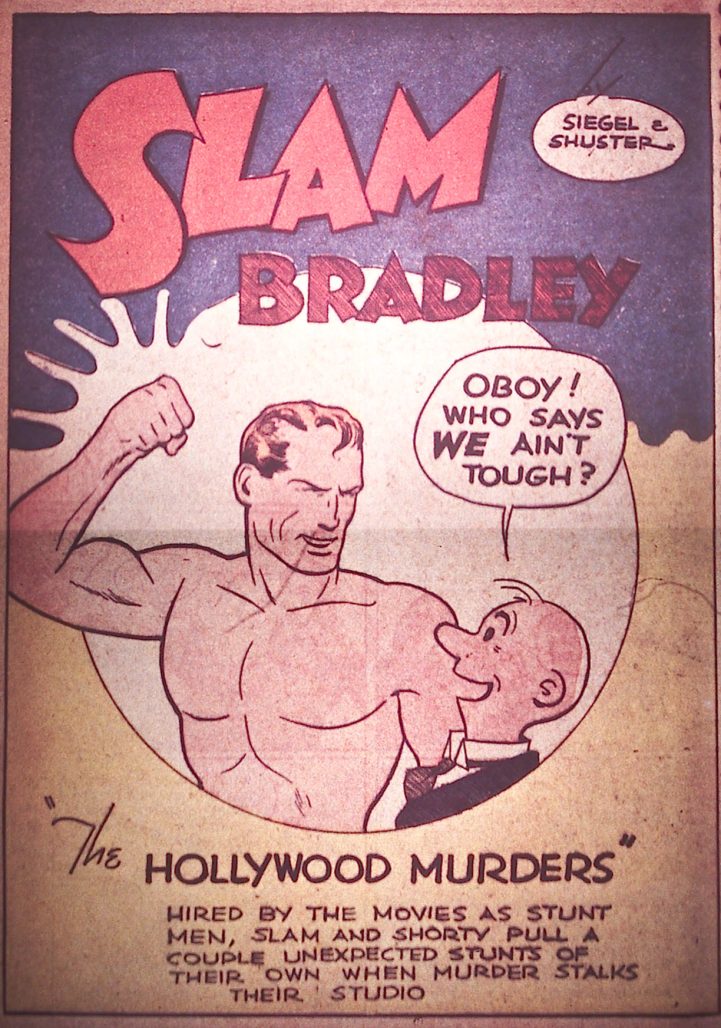

Slam first appeared in Detective Comics #1 in March 1937. The comic was produced by Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, military man, pulp writer extraordinaire, and the person who published the first American comic book of original material with the landmark 1935 New Fun. The early issues of that series featured the first national comics work of two young men from Cleveland named Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who were assigned the Slam feature in Detective.

Basing his look on Irish pugilist-turned-film star Victor McLaglen, Siegel and Shuster produced a memorable run on Slam Bradley centered on adventure stories, mysteries, and Hollywood sight gags. They worked together on Slam until 1939; Jerry went on as writer for longer.

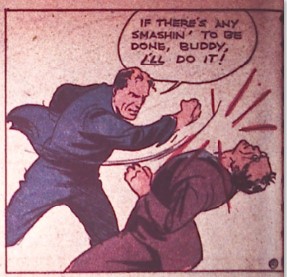

Slam is good thirties sock ’em comics in the vein of Wash Tubbs, Captain Easy, Terry and the Pirates, and Brick Bradford. Every episode has a different setting, as Slam and his comedic partner Shorty Morgan take on private investigations and globe-hop from Egypt to Mexico and back to their hometown of Cleveland, foiling slave traders and spy rings, crooks and wild animals.

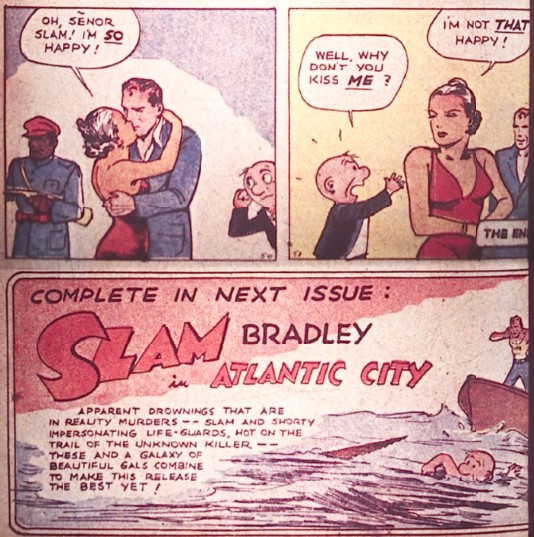

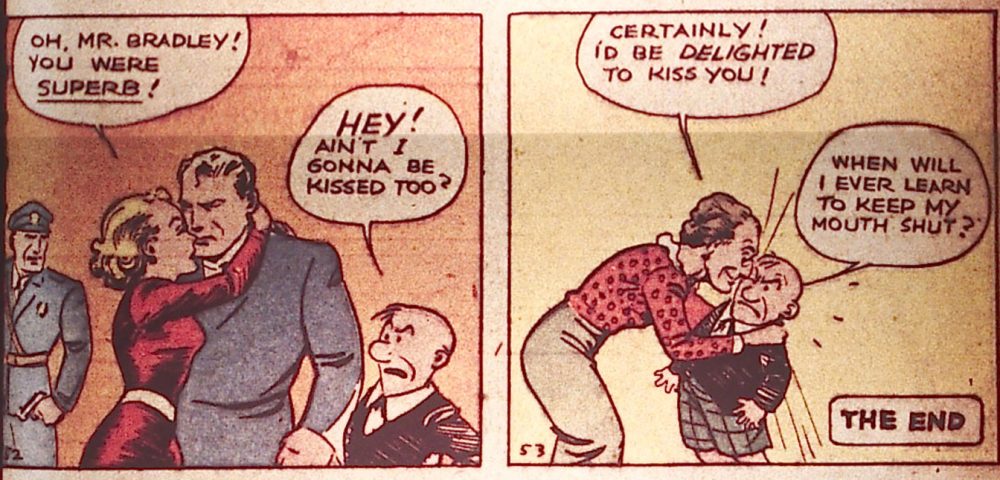

The stories are formulaic, but never boring. Slam wisecracks, beats a bunch of people senseless, uncovers the villain in a Scooby-like ending, and kisses the girl. Shorty, who is always lamenting this foregone conclusion, gets all the good lines and looks a bit like Mr. Mxyztplk, who would not appear until Superman #30 in 1944.

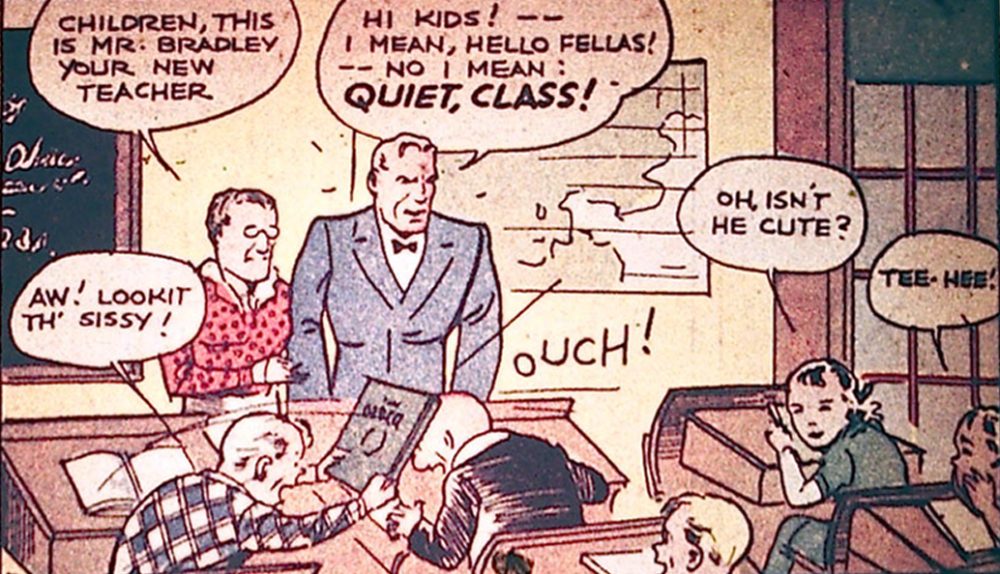

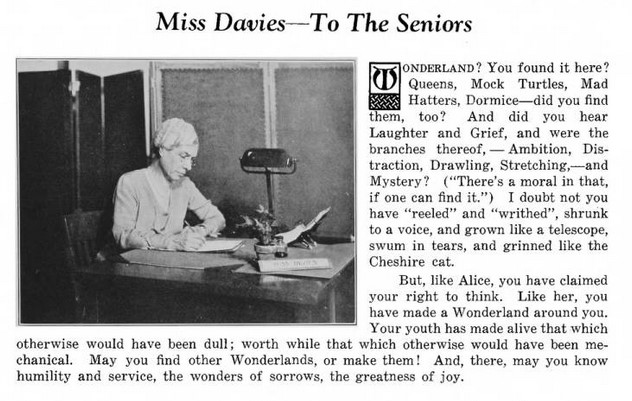

Most of the stories are fun, solid comics in the underappreciated Siegel and Shuster style: jokes galore mixed with massive widescreen action. The creators complemented each other perfectly. And as with Superman, Siegel and Shuster made Slam into a kind of imaginary autobiography, putting in places, people, and events from their own lives. In Detective #5 (1937), Slam and Shorty return to their old school of Glendale and pose as teachers to solve a mystery for the assistant principal, who looks exactly like Miss Elsie Davies, the real assistant principal at Siegel and Shuster’s own alma mater of Glenville.

Slam even gets to kiss Miss Campbel, named after the real-life English teacher at Glenville.

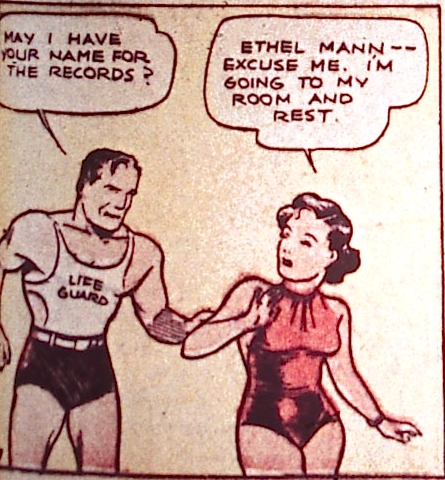

The Slam stories are loaded with stuff like this. In Detective #16 (1938), Joan Carter, who modeled for Siegel and Shuster for the character of Lois Lane, appears under her real name — and beats Slam out on a case. In another story, Slam rescues Ethel Mann, who has the same name as a local swimmer the boys had a crush on in high school. This kind of autobiographical content isn’t mindless, it’s what Klimt called “a line around your thoughts” — it is art that is both personal and fantastic. It may be juvenile, but it is also juvenilia. It’s bold and confessional — they didn’t even change the names of some of the people they wrote about. The Slam stories show Siegel at his best on the tightrope of adventure and comedy. And Shuster? His fashion, anatomy, and at times minimalist faces allowed readers to recognize these characters as if they were full-bodied extensions of McCloud’s smiley face. This was an evolution moment for long(er) form comics in book form.

At times, Slam comics sometimes feature racist caricatures, often depicted as endless waves of dehumanized criminals and dialect-heavy stereotypes played strictly for ridicule and criminality. They are hard to look at and listen to.

The women characters mostly occupy a similar space: they are often feisty but exist in a very objectified way to be ogled, rescued, kissed, then discarded forever to the limbo of single-issue appearances.

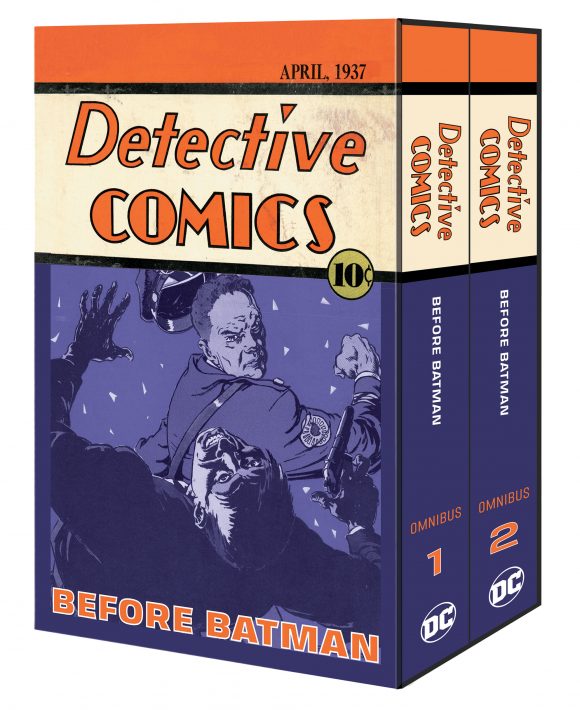

A new two-volume omnibus reprint of these early Detective Comics stories — which have never been collected except for on microfiche many years ago — was recently solicited but ultimately cancelled, possibly due to these depictions, though no official explanation was ever given.

The Slam stories are a vital and under-explored moment in the history of the comic book. Many say he was the prototype for Superman (I mean, look at him), but by the time Slam debuted, Superman not only already existed (in one form since 1933), but was being actively shopped around, including to the Major, who was very encouraging of the idea. No, Slam was his own thing. And as the longest color feature in Detective, it might have been the bridge from the newspapers to comic books. Kids may have followed Siegel and Shuster to Action Comics based on Slam, who also dovetailed right into Batman almost exactly two years later when their contract on Slam was up. Slam may have been the gateway character that sustained the comic book experiment until the superheroes showed up. If Superman is the foundation of what would become DC Comics, then Slam Bradley is the footing, buried away as the first part of the now-towering structure.

I’m a teacher. I think everything should be taught, history should be objectively honest, and you should only burn books if you’re stranded in the wilderness and there are no trees in sight (and even then just the dust jackets and acknowledgments). But I think DC was absolutely right when they scrapped the Slam reprint.

I live in Cleveland where our baseball team has finally gotten rid of Chief Wahoo, its longtime racist cartoon mascot (note: we also had a deep run in the playoffs this year/coincidence?). Yet here in Cleveland you can still see Wahoo as some people continue to wear their undead caps around in acts of individual defiance. The difference is that if you go to the official MLB.com team store, you can’t buy a new Wahoo. You can still go to the Cleveland History Museum and see a huge sign of him that graced the old stadium, but it’s there as an artifact of the past to look at and think about. It’s not something new. I think that’s the key point about reprints. Racist comics should probably not be reprinted as a saddle-stitched, high-end product with a handsome slipcase for largely upper middle-class collectors to take glamour photos of for Reddit threads. This part of our past should not be ignored or filed away, but it should never be seen as valuable. It shouldn’t be something to collect.

Instead, what if DC offered the early Detectives as a cheap (or free?) PDF for educators and students? Or for anyone? With historical context from experts in these specific fields of comics scholarship, not just the same names we always see on these things. Look at those gorgeous Penguin Marvel books. There are ways to do it.

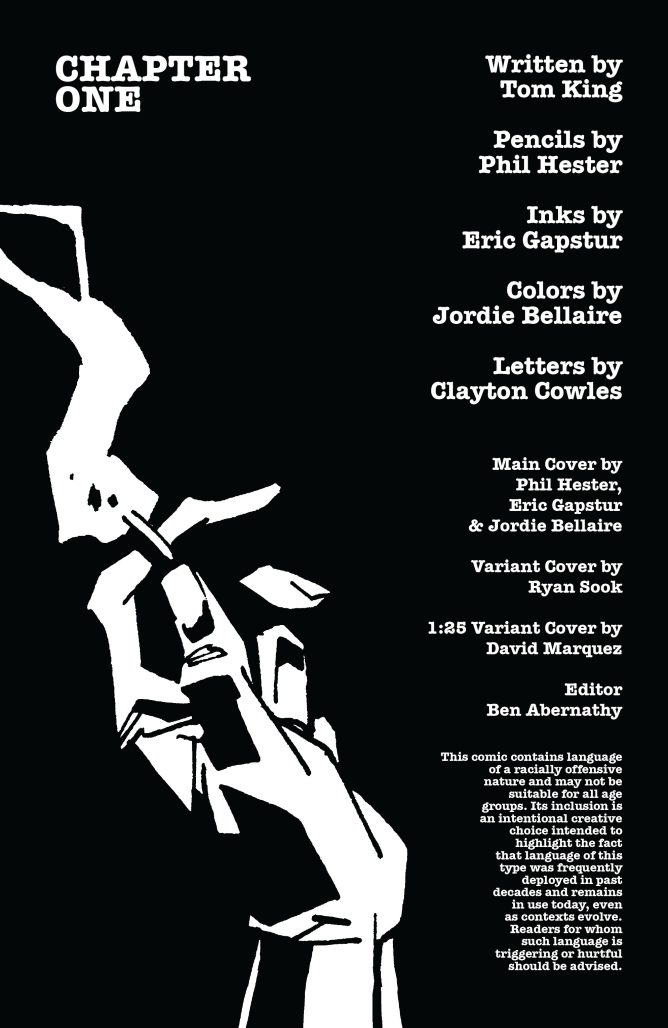

Which brings us back to the present. The title page of the new Gotham City: Year One bears the following warning in the bottom right-hand corner:

That both versions of Slam — the old and the new — require a disclaimer (or should) is perhaps next-level Tom King work that makes comics art perform comics history. So why can’t we slap a similar disclaimer on the old Slam Bradleys? The difference is subtle but important: King is using the racist language in his book to make a commentary about the past. The old Slam comics are simply the past itself.

Why does that matter? Because times change, and eighty-five years is a long time. And Slam is even older than that.

On May 13, 1936, the Major wrote to Siegel about the character he wanted them to work on next.

We want a detective hero called Slam Bradley. He is to be an amateur, called in by the police to help unravel difficult cases. He should combine both brains and brawn, be able to think quickly and reason cleverly and be able as well to slam bang his way out of a barroom brawl or mob attack. Take every opportunity to show him in a torn shirt with swelling biceps and powerful torso a la Flash Gordon.

They weren’t alone.

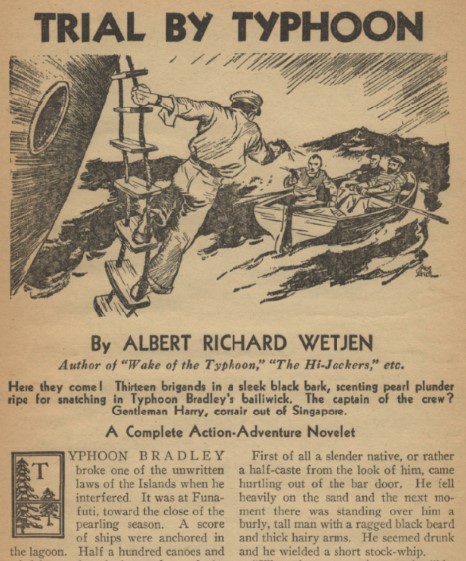

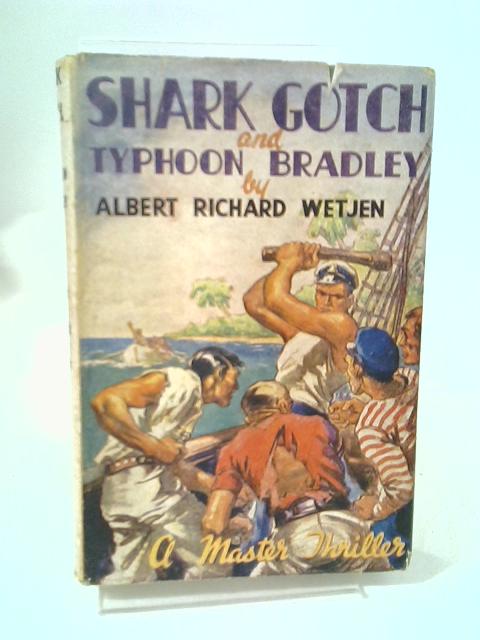

Typhoon Bradley was a pulp character written by Albert Richard Wetjen that appeared in over twenty pulp stories beginning in 1928. He sailed his boat all over the South Pacific beating up pirates and the occasional man-eating shark. He had a lust for physical violence and would often take on whole ships of men with only his own bloody knuckles.

Typhoon Bradley was he-man, alpha male toxic pulp masculinity at its frothy apex. His adventures were also exceedingly racist in their portrayals of the descriptive mangling of “evil Chinamen” as well as the horribly stereotyped islanders that Typhoon brought to heel. They were loud, cruel stories.

My point is that though the specific character of Slam Bradley was created for Detective Comics, he was part of a much longer tradition of supermen before there was Superman. They are all part of a lineage that includes Slam and Typhoon Bradley (who was based on an even older pulp hero named Hurricane Williams). Does this mean the racism and sexism in those stories can all be excused by a single commenter somewhere posting “Who cares? They all did it! It was the times!” Of course not. That they all did it means that it was bigger in scope than we can sometimes imagine. Were Siegel and Shuster perpetuating the same racist and sexist tropes? Or were they altering the Typhoon character by making a parody of it?

Gotham City: Year One #1’s noir-black title page above, drenched in ink, also covers up something else. Though I will not pretend to understand why only some creators get credit and how and where and when and what that all means in terms of rights, royalties, or none of that (or all of that), I do know that with Slam Bradley we have a clear paper trail of historical documents that name his creators right down to their signatures. I know we’ve all had to deal with this before and it gets old, I know. But it’s still important. So when you see that title page, especially after this year we’ve had, think of Slam’s creators, all three of them. Or get a pen and write the names down yourself, right by the flickering match. Because even in the dark, they are still there.

In a way, that disclaimer is more than just a trigger warning; it’s also kind of an admission — and an apology — for all that came before with Slam Bradley. That’s important to acknowledge because, as the disclaimer says, this type of racist thinking “remains in use today, even as contexts evolve.” We — and Slam — cannot escape the past, even when we evolve, for the simple reason that we know we have not, not all the way, even though we’re still trying.

Brad Ricca is the award-winning author of six books, including the new graphic novel adaptation of Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-house with artist Courtney Sieh, nominated as a Great Graphic Novel for 2023 by YALSA and named to the “Best New Comics of 2022″ list by the New York Public Library. Follow @BradJRicca.