20th Century Men

20th Century Men

Writer: Deniz Camp

Artist: Stipan Morian

Letterer: Aditya Bidikar

Publisher: Image Comics

“Beyond the immediate outcome of the struggle, which was most often inevitable, their combat was for history, for memory… this affirmation of life by way of a sacrifice and combat with no prospect of victory is a tragic paradox that can only be understood as an act of faith in history.”

–Alain Brossat and Sylvie Klingberg, Revolutionary Yiddishland: A History of Jewish Radicalism

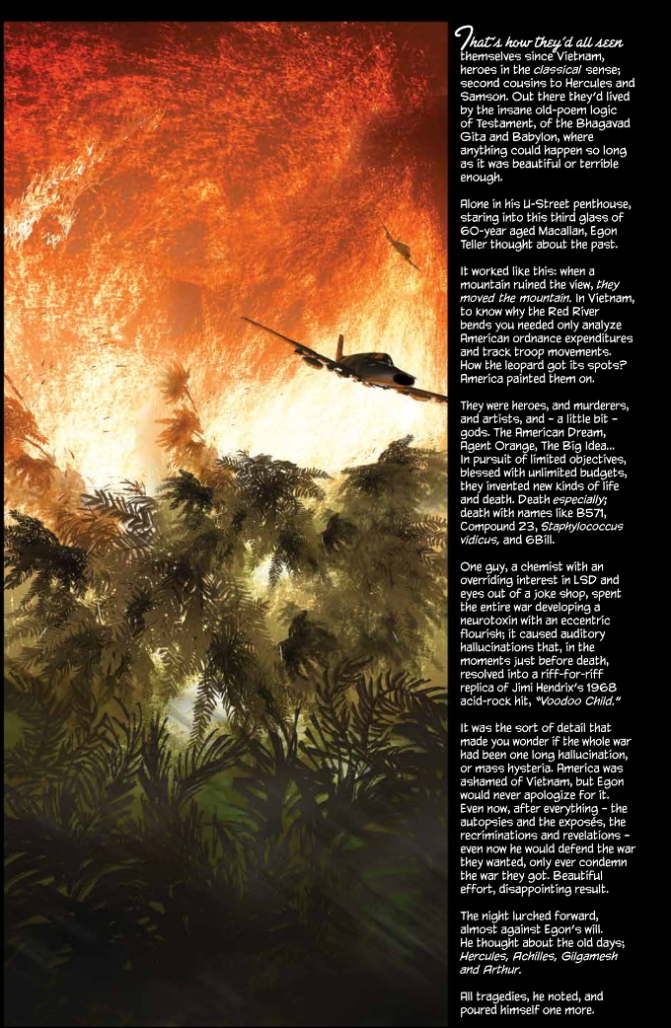

In a sea of blood and violence, in-between alternate political histories and painful explorations of colonialism, with frighteningly accurate caricatures of national leaders and their motivations, 20th Century Men — by Deniz Camp, Stipan Morian and Aditya Bidikar — is perhaps one of the most cathartic, and well-realized comics of this or any other century. There is a quiet comfort to this tale that stands out to me from the opening pages, all the way to the bloodsoaked conclusion. While you are faced with challenging visuals and the horror of oppressive states rendered in vivid detail, the comic provides a simultaneous cleansing release. The book leaves you with a sense of peace and contemplation after you’ve closed the last page that works in harmony with the violence inherent to the subject matter.

This is in large part because it’s a story that gives both a eulogy to the foundational figures of colonial rule and provides a voice to the resistance. The men who shaped the past are faced with their own mortality in a way that represents the eventual decline of any existing empire. The balance struck here is one that is careful not to be nostalgic for the glory days, nor giving a superhuman portrayal of the resistance mentality. Every aspect of this story is utterly human, encompassing all our faults, immorality and spirit while also inserting itself into the alternate history superhero genre.

At its core, this is a story that asks “what if superheroes were real?” with a 2000AD stylistic spin, but it flips the script on how we understand that premise. We are not talking about Superman, we’re talking about the literal expression of what a political superpower is, and how that power manifests over the course of history. There are countless comics that take the premise “what if superheroes were real?” and combine it with an alt history, but those stories are still supplemented by standard superhero genre troops. Invincible has Omniman as their Superman stand-in but the story is still functionally just a regular superhero comic, the same can be said of Plutonian in Irredeemable/Incorruptible. And while there’s nothing wrong with that, this is a top-down approach. That is, these are stories constructed from a world-building mentality where every aspect of the standard superhero story is checked off and allowed to run parallel to the real world.

In contrast, 20th Century Men is a comic that grounds the emergence of a “Superhero” within the historical confines of a world that has its own uses for super powers, its own forces of history, its narratives that the hero needs to fold into.

20th Century Men is not about a superhero who has come to represent oppressive ideology, à la Fascist Superman from Injustice. This is a story from the ground up of how existing foot soldiers of ideologically oppressive empires make themselves up into superheroes. The story of the “great” men of the 20th Century is the story of the mobilization of history to make us believe any one political figure can be more than just a mere mortal man, and that the lengths they would go to in order to preserve that image are at the expense of the rest of the world.

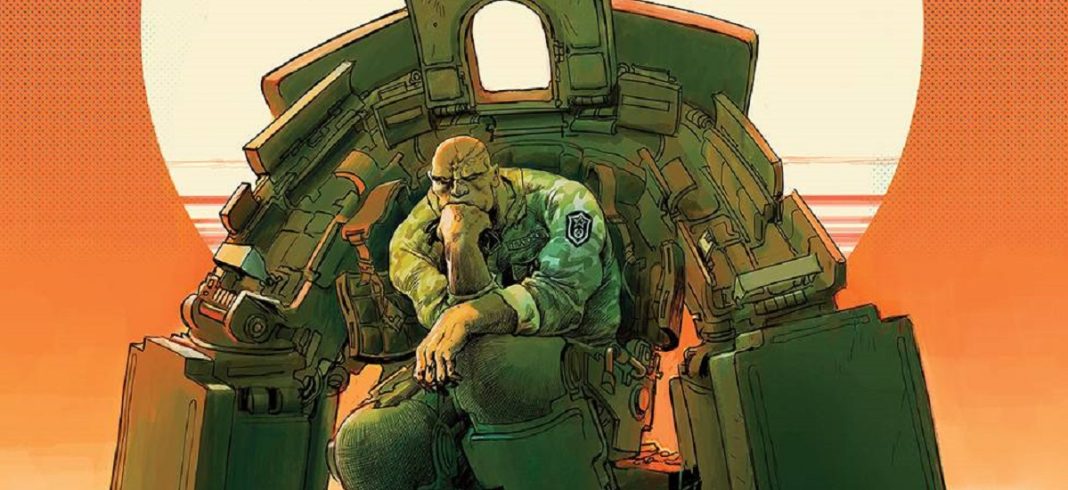

There are two main expressions of super power in this story: Petar Fedorovich Platonov, a Russian born scientific genius taken by the state at a young age, and Thomas Goode, a former WWII super soldier turned American President. In his art, Stipan Morian is depicting both of these men as beaten down by time. Platonov’s suit is large, heavily detailed and imposing but at the end of the day he’s just a small man at the center of it, looking like he’s preparing his last breath.

He’s scarred, he’s tired and his suit is a shield from the inevitably of his own eventual death. Similarly, we first meet Thomas Goode as tall, muscular, commanding but not immediately able to get his way. Both are men of fragile egos, fighting each other endless without ever really accepting the fate this leads to. Morian is crucial here in taking the time to render the quiet personal worlds of these characters in vivid detail, but also lean back and allow for some restraint that lets the exaggerated body language and color palette do as much, if not more work as the dense pencils.

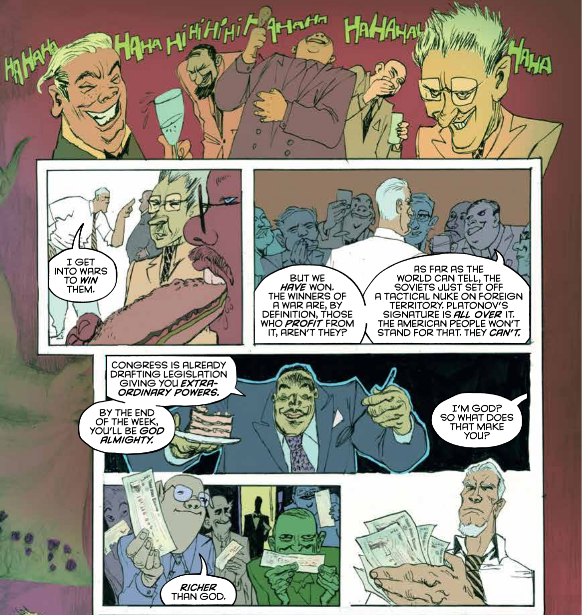

The remaining characters navigate a world dictated by these two ideological pillars, though importantly even Platonov and Goode are not free from the influence of the society they helped create. Despite being president already, Goode still sees himself as a soldier, he still has a need to portray himself as an invincible leader. And even he is blind to the real powers of corporate greed that sway ideology. He’s a man of the past, attempting to form a legacy around his image, unaware or unwilling to admit that that power to mold history in any direction was never completely his own.

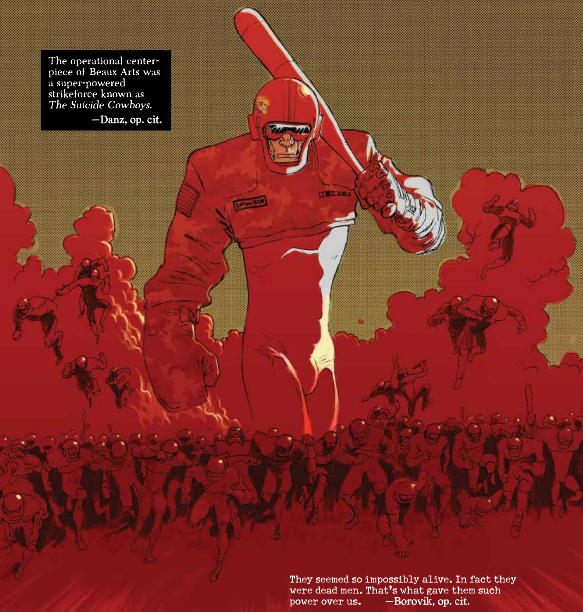

Goode and Platonov are not the only superhero allegories here. We’re also introduced into the American Suicide Cowboys who are dressed like Football players, running into a combat zone like its a playoff game. The aesthetic is at once childish and perfectly propagandistic. It shows the ways in which heroes, in the form of capes or team jerseys, allow for a rallying cry that forces us to forget our identity in the service of being carried away by an abstract idealism. It’s a distillation of the hero worship we experience daily, iconography representative of ideology that makes us want to be something other than we are.

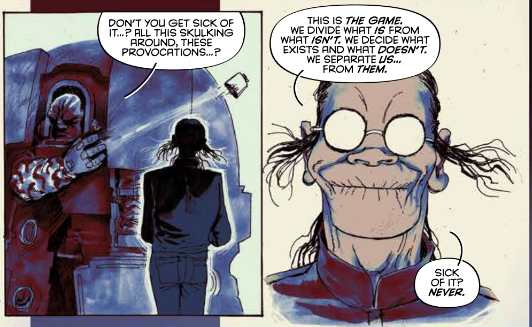

The key to this exploration of heroism and power is that the book demonstrates how history is a social production. That, to paraphrase Michel-Rolph Trouillot, history is both what happened and what is said to have happened. History constitutes not only the facts of the matter, but the narrative. And that narrative is the framework by which the facts are assembled, such that any interpretation of historical records is also an expression of the ideologies that inform what we take to be important, what we take to be “a fact” that is a matter of record vs an anecdote that can be dismissed.

Heroes are exactly the kind of ideological narrative work that helps to mold history. Seeing any one person as a hero is to give them a higher level of agency over the world around them and attribute to them greater action than any mortal may be capable of. The need for a super powered nation to have a superhero, then, is to help them convince the world of its virtue, to encourage a mentality that forces people to see the course of history as an inevitable consequence by powers greater than you.

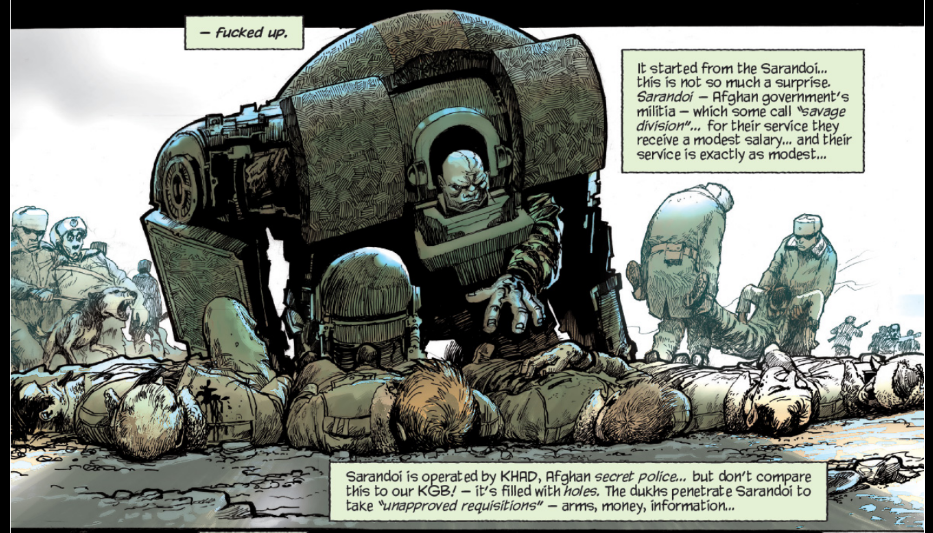

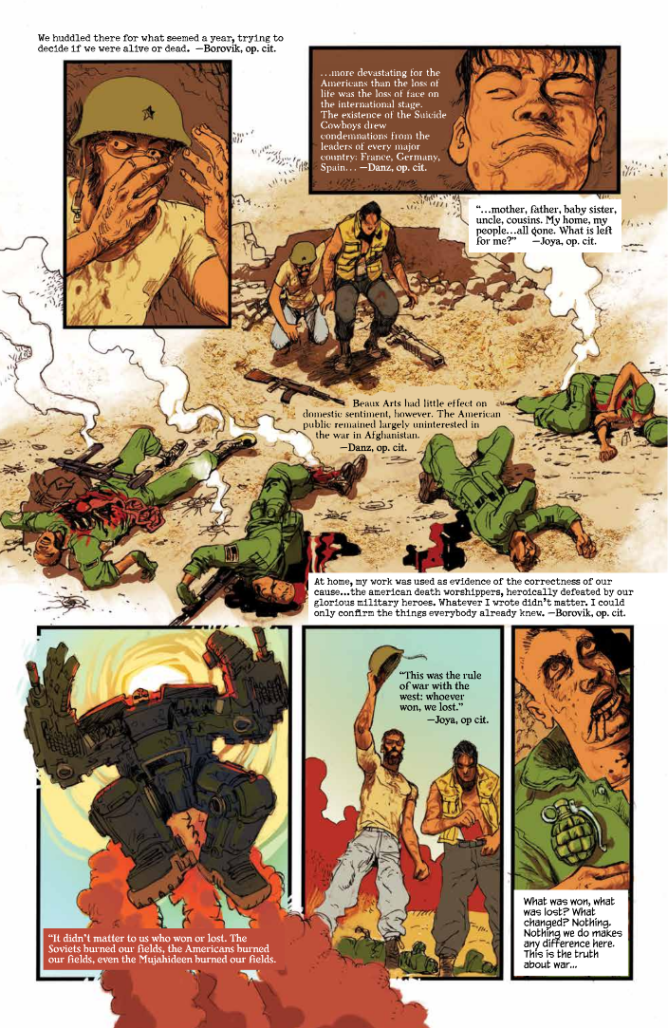

Nowhere is this more clear than in issue #4, wherein we see the clash between the Russian Super Soldier Platonov and the American Suicide Cowboys. The story is framed through various primary and secondary accounts of the battle, both from witnesses and what appear to be retroactive analysis of the battle’s historical significance. We see plainly before us what is happening, we are not at a lack for “facts” with which to construct a history. We are, however, unable to come to a meaning or interpretation of these facts without particular ideological frameworks that anchor what is and isn’t important. In one sense, the battle was a tactical success for the Soviets, led by a masterful strategist in the form of Platonov. Conversely, it was a demonstration of the undying will of the American people to put themselves before certain death without hesitation for their county.

Most importantly, however, is how the battle zone of Afghanistan’s own experience is expressed through Frazana Joya, who at the time was only 6 years old and reflects on how the war eclipsed the people’s own right to self-determination. Joya’s own document is titled “How to Live,” in contrast to the propagandist other titles we see, such as “The American Dream: The Approved Biography of Thomas Goode.” Joya reflects on the history presented to her as it defines the ability to continue living, whereas the rest echo the way all other parties wanted to be remembered.

“The situation was completely under my control. Victory was never in doubt.”

Platonov, op. cit.

“Thomas Goode is the devil. But it’s devils you need in work like this.”

Scripted People: Memoirs of an Intelligence Agent, Win Everett.

“All we ever wanted was freedom from western invaders.”

Joya, op. cit.

As the issue progresses, the instrumental nature with which both parties treat Afghanistan comes into full focus. Platonov’s goal is completely abstracted, unclear from the perspective of the battle on the ground. Goode’s focus is merely the antithesis to Platonov and nothing more. Meanwhile what is to be gained from the treatment of a sovereign nation as a playground for super powers is brought to the center, “we never understood what the West wanted from us,” expressed Joya.

If issue #4 is the argument for history as social production, then issue #6 culminates the series in a proposed alternative to that specific history. This is a chance for the voices who are silenced between the superpowers to provide their own testimony in the historical record. The issue opens by contrasting America’s “once upon a time…” and Russica’s “a long time ago…” with Afghanistan’s “it was and it wasn’t.” The American and Russian framings are backwards, glorifying the past as the inevitable unfolding of a bright future. It looks at the world as it was presented one way and assumes a clear trajectory to the present moment.

This is a common element in how empires preserve certain ideological frameworks that help shape their goals and future. In order for an ideology to take hold it must not only be expressed to the populace, but reinforced over and over again. The production of history is one of the many ways an empire, especially one in decline, may preserve the ideology at their center. As Terry Eagleton once argued, there’s a correlation between, for example, the decline of Britain’s place a global superpower in the 20th century and at the same time the rise of British Literature that exalted the Elizabethan Era, or as Nietzsche wrote of the divided states of Germany emphasizing Ancient Greek history, who existed in a similar historical context of divided city-states aspiring to the power that comes with unification. In both cases, when your present seems outside your control, you look to the past to justify your existence and to breed nationalism.

Thus, repeating the myth of your own superiority, framed entirely in hindsight, is representative of a failing empire searching for meaning. No one needs to believe “the sun never sets on the British empire” more than the British people themselves. Or in this case, the only way for American and Russian super soldiers to justify their relevance in a changing world is to reaffirm the histories written about them, again and again.

The struggle from the perspective of Afghanistan and Azra in the climax of this series to find a space for their own existence in a world defined by the totalizing wills of empires who refuse to die. In her proposed utopia, we’re faced with a classic struggle between postcolonial and decolonial dialogues. In the first sense, how does one choose to live in a world defined by an empire? Can you build something that is simply yours? And in the latter sense, can the totalizing effect of wars past be rejected? Can you unmake what the world has made you into? Certainly there is no easy or correct answer to this but a unifying conclusion that can be drawn is a need to struggle, to form a history that tries to rectify the silences imposed by larger empires. The ethos of this struggle is not dissimilar to what what Lê Duẩn expressed about the American War in Vietnam and why the Vietnamese resisted what appeared to be insurmountable odds: “We knew they could not stay in Vietnam forever, but Vietnam must stay in Vietnam forever.”

20th Century Men is a singular masterpiece of the comics medium, and a focused tome on the essence of decolonial thought. While chronicling the extinction of old forces of power, it pays close attention to the struggles left in their wake. As bleak, bloody and bold as the political commentary is, the series preseverses the agency of those who resist the totalizing ideology of superpowers. It’s both a book of mourning and the spark of revolutionary fiction one needs in the present day.

Final Verdict: BUY

20th Century Men is out now.

Read more trade collection reviews every Thursday in our Trade Rating column!

Outstanding review by Steve Baxi. Some of the best written criticism I’ve read so far on the Beat, and I’ll be looking for him in the future. 20th Century Men is a great overview of the superhero genre, and the artwork puts a lot of American comics to shame. Great stuff, and thanks for promoting comics other than the big two.

Comments are closed.