Most science-fiction stories set in the future are set in the far future because that invites less criticism over scientific accuracies. The creators of The Dark, however, were more than happy to begin their graphic novel less than 20 years from 2019. Mark Sable’s work as a futurist helped him ground the ComiXology Originals graphic novel in a world that feels plausible and that world is brought fully to life by the art of Kristian Donaldson. In a lengthy discussion, the two of them discuss their influences, feelings about the future, and the immense amount of work and passion put into the making of The Dark.

How did The Dark originate?

Mark Sable: Year ago, I wrote a comic called UNTHINKABLE, about a fictional writer joining a real-life think tank where writers were tasked by The Department of Homeland Security to come up with worst-case terror scenarios. In a strange bit of life imitating art (imitating life), in the past few years, I’ve worked as a futurist, including for The Atlantic Council’s Art of Future Warfare project, where work with the military, intelligence, business, and scientific communities to help envision the future of conflict.

As part of my work as a futurist, I wrote a short story that became the basis for The Dark. I was intrigued by the rise of biotechnology, particularly the potential of biocomputers and the idea of biopunks who could hack their own bodies.

I began to think about what kind of world would need biotechnology and thought about a world where silicon-based technology had been rendered useless or too risky. This was around the time of the STUXNET virus that the U.S. and Israel allegedly used to take out the Iranian nuclear program, so I envisioned a world devastated by a world-wide cyberwar. In such a world, there would be little to no electrical grid, and no one would trust an Internet that spread such an attack.

But, I knew there would still be a need to collect and store data, and I imagined that the NSA would use transhuman agents and biocomputers to do what we do with silicon-based computing now. This was also the time of Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning’s leaks, so I started to imagine how someone would be able to steal data in this biotech world.

With the seeds of the world planted, it was time to cultivate characters that would make for a compelling story in that world. I imagined Camille, an NSA data analyst turned apparent whistleblower, and Carver, a former cyber-soldier turned government agent tasked with hunting her down.

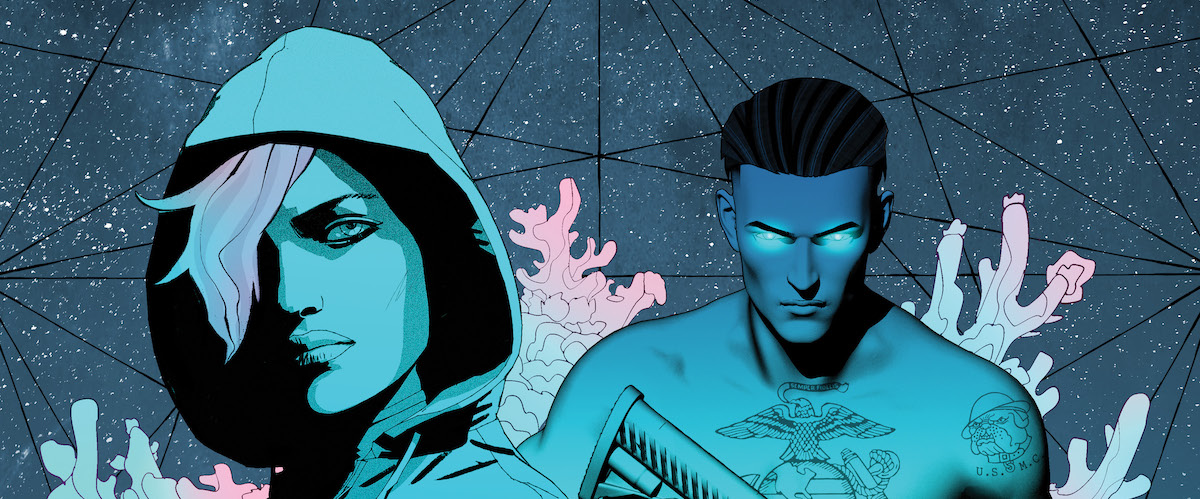

I hadn’t thought about adapting the prose short story into a comic, let alone a 120-page comic until I came across Kristian Donaldson’s art on Instagram. Kristian had drawn a cover for Unthinkable and we’d talked about working together in the past, but what I saw him post was on another level. He’d completely reinvented his style with the 3D images of abandoned military installations and discarded aircraft. I found it so transcendent that I knew The Dark had to be a comic and only Kristian could draw it.

Kristian Donaldson: Well, I got Mark’s attention by infiltrating Area 51 way before it was cool. I’d spent a few years exploring secret military installations and rappelling into decommissioned missile silos. Mark had been doing his intelligence thing all around the world, and we met on the runway of Spaceport America while Richard Branson and Elon Musk were drag racing prototype EV’s. He gave me the smuggled documents and the suitcase full of money and I got started.

Kidding. I’ve known Mark since 2004 when we both had our first books out at Image. We started talking seriously in 2017 after Mark saw a book I worked on called HIGH STRANGE available from AA books. It’s a book of environment concept art of lonely and ominous rocket pads and rotting missile silos, based on military/UFO folklore of the American Southwest. (with Liam Young and Kate Davies of The AA.)

Mark liked the world-building feel of it and thought we would be a good match on building a fresh world for The Dark. I actually rolled a lot of my existing concepts like that right into The Dark, with Mark supplying the BioTech aspects as the new angle to explore. So you’ve got this sort of government military remnant with a rolling wave of biotechnology just rushing right over it and around it.

When did ComiXology enter the picture?

Sable: Very early on, I showed a few pages of art Kristian had done for a pitch to Chip Mosher while we were having dinner. He immediately asked for the story and ComiXology bowled us over with an offer we couldn’t refuse.

Donaldson: Mark showed Chip Mosher our standard 5 pager Image style pitch, which I drew late 2017. I’m really glad that everyone was receptive, first Mark, who was really enthusiastic and then Chip, who was stoked in a way that rubbed off on me early on. Ivan Salazar was right there from the start and helped me integrate with comiXology in a big way. When Mark and I were first talking about this project I knew I wanted to do things as new and different as possible, from the way it looks, the way it’s made, distributed, read, everything and we came together with the right people for that. They gave me the resources and help I needed to make the art production a success and once Lee Loughridge, Thomas Mauer, and Will Dennis were there working deep on the final book it was clear how much effort and support were in play.

The opening pages of The Dark have an almost lyrical quality because of how the captions and occasional dialogue bounce off each other. Was your writing process different when scripting the beginning of the book?

Sable: Yes. I don’t think I’ve ever done as many revisions for a comic as I did with The Dark. That’s because right up until the end, Kristian and I would go back and forth over outlines, scripts, and art.

I was obsessed with world-building and character, and in addition to Kristian’s gift for bringing anything mechanical to life, he is an incredible action choreographer. Even 120 pages didn’t feel like enough to get everything we wanted in, but somehow we did it. Later Lee Loughridge would transform the book with his colors, Thomas Mauer with his lettering and design and finally Will Dennis came in to lend his legendary editorial hand to make the whole thing seem seamless.

We also had tremendous input from Mey Rude. Camille, the co-protagonist, is trans, and she is a sensitivity reader that we hired as an editorial consultant. In addition to trying to guide my understanding of trans identity, she had a big role in helping shape Camille as a character.

All that is to say it was the most collaborative scripting process I’ve ever been a part of, and I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

The story essentially begins in 2035. How did you decide on that time period specifically?

Sable: The first act of the book takes place in 2035, showing the cyber attack and the devastation that follows in its aftermath. Then we flash forward to 2045 when we see biotech just starting to replace silicon-based tech.

In both time periods, it was a case of close enough that the world seemed familiar and the threats possible, but far enough away that some truly astonishing breakthroughs could happen.

A lot of writers choose to tell stories set in the distant future, but The Dark takes place only 16 years from modern day. What appeals to you about setting a story in an age that readers will live to see?

Sable: I should be clear that, although I’m a futurist, THE DARK is not any kind of prediction of what I think will happen in 15-25 years. While I did a lot of research, the research was to ground a cool story in some kind of plausibility, rather than trying to write a story to justify a particular vision of the future.

That said, some of my favorite sci-fi has been near-future – Blade Runner and Neuromancer being two examples that were also influences. What appeals to me about THE DARK and the time period we are talking about is that the issues facing the characters are ones we are dealing with now.

How secure is the Internet? What does it mean that we’re moving rapidly towards an “Internet of Everything” where not just phones and computers but light switches are connected. How vulnerable does that make us if that technology fails?

People talk about the singularity involving AI, but I feel like we might be sleeping through a different kind of singularity, one in which as human beings we are almost forcibly connected not only to technology but to each other through, among other things, social media. What happens if those connections are severed?

Donaldson: A lot of the science and tech stuff is already here or will be here even sooner than we think. We just don’t have enough cohesive popular images to see it all happening in real-time. You get the news-clip summary of all of this amazing work being done across all of these advancing fields like robotics, exoskeletal tech, ballistics and body armor, genetic and biotech medical weirdness, architecture, energy, all this stuff…but you need a story to show these things working in concert towards a future, and that’s what this book is in a lot of ways.

What kind of research did you do to write the graphic novel?

Sable: I’ve always done a ton of research for my books, and in the past that mostly involved reading an exponential amount more than I end up writing.

Working as a futurist as well as a writer these past few years though has given me access to people that I wouldn’t have dreamed I’d be able to talk to. CIA personnel, astronauts, AI researchers, Navy Seals, etc. Sometimes that would involve me reaching out to them to ask specific questions, but more often than that, I tried to soak as much (non-classified) knowledge as I could in.

Those conversations inspired me to read and learn more, which in turn inspired more questions. Although I’m often hired to come in and teach creativity, I find interacting with such accomplished non-writers to be have sparked my own creativity.

Donaldson: Mark supplied me with a lot of good things to check out. right away it’s like: exoskeletons! military armor! vtol aeronautics! robotic battlefield dog! so I’d group these things and look for 3d models and pieces of 3d models and start building quick concepts, looking at them from all angles and make some test images and 3d bash some more. I have a huge library of 3d assets that I’ve curated for years, it’s a full armory and vehicle collection. Architectural and technological components for days. So when Mark writes a script, I list an inventory of what actually shows up in frame, and dip into my library first. So it’s like okay, Carver is living on this off grid ranch..so, let’s make a shipping container house, add some solar panels, park a jeep in front, put a barn and tractor over there, etc. add characters and you start to have something to hang story on. So the bulk of my research was model-based and dealt with lots of file organization and model bashing. If I want a piece or a shape, I build it or source it quickly. There was this idea of biological architecture which was way different than the linear architecture I had been leaning towards, so that was research-heavy, what kind of forms read as buildings and looked good in a comic frame, how you’d arrange a loose grouping of elements to look like a cityscape. And for this idea of biological computing, I thought it would be fun to design organically grown computers in a few different styles based on coral growth, cordyceps fungus, and human brains.

Was it hard to read about changes to the world that could lead to such a gruesome future?

Sable: Researching the future I tend not to get as scared as when I’m researching the present. Whether it was watching Afghan war footage for GRAVEYARD OF EMPIRES, or listening to a first-hand account of the present-day conflict in Syria and The Philippines for an as-yet-unannounced upcoming war-related project, I’m more disturbed about what’s going on today than what might happen tomorrow.

Donaldson: Of the numerous gruesome futures we could face, I think this one is actually pretty cool if you survive the first year or so. The major vulnerability of a centralized utility is slowly replaced by a patchwork of renewable and biotech common utility. There’s the trans-humanist aspect of changing or repairing or upgrading yourself as an organism, which could offer humanity a lot of durability, longevity, and variety. But seeing how much our power grid sucks is hard to take, like in California right now. American infrastructure is not that great anymore compared to the rest of the world and we’re so slow to react or change anything that it’s a bit disheartening.

Do you think technological progress eventually leads us to a world like the one presented in The Dark, where technology ultimately does more harm than good?

Sable: I think I write about dystopia because it provides more dramatic possibilities for me than utopias do, but I’m not necessarily pessimistic about the future. Technology has always had simultaneously good and bad effects. It’s lengthened human lifespans and reduced mortality rates at the same time it’s threatened nuclear or ecological catastrophe.

Barring, quite literally, the end of the world, I see those same trend lines continuing. To me the future we present in The Dark is neither good nor bad, but like the present…it just is.

Donaldson: I’m sort of an optimist. I think industries will see there’s profit in going green and clean eventually, and material science will change where and how we live. We still build buildings and burn coal and deforest like it’s some Victorian-era dirty gilded age capitalist thing that will never end, but I think this century hopefully in my son’s lifetime there will be a major shift in how we live for the better.

The Dark is ultimately a story about connection. Do the scientific advances in The Dark help people find connection, or actually make it more difficult?

Sable: When the story starts in 2035, humanity is at its most connected. We see that most especially with Carver. He’s a N.E.O., or networked exoskeletal operator, which means he can see, hear and feel everything he and his fellow soldiers are experiencing and vice versa. It’s designed for optimal battlefield awareness and unit cohesion.

But when Carver is the sole survivor of an attack on his unit, that means he feels their deaths, and then their absence, even more acutely. In the Internet-free world of 2045, he is happy to be free of connection. In his mind, connection inevitably means loss, and he’s determined never to feel that again. Still, the new biotech revolution has given him Mars, a genetically enhanced service dog with whom he shares a deep bond. Carver and Mars are forced out of isolation to hunt Camille.

Camille, on the other hand, thrived in the connected world of 2035. The Internet gave her anonymity and allowed her to transcend her body, and what others thought of it. Working with – and stealing from – the NSA’s biocomputers in 2045 gives her a chance to do something present-day technology couldn’t. A transition on a genetic level that she believes will help her connect more deeply with others, and more fully with herself.

Then we throw a third character into the mix. Magnussen is a metadata magnate who lost his empire during the cyberattack of 2035 and wants to create a kind of biological internet to replace what was lost. And he’s willing to go to extremes to do so.

Each of these characters feels that science has made them more or less connected at the beginning of the story, but as they connect with each other, their feelings change radically.

Donaldson: I’m the recluse here, so I sympathize with Carver hiding out in his solar-powered cabin towards the beginning of the book. His feeling is the more connected you are the more control you lose and the more pain you open yourself up for. That’s Carver’s struggle in the book, on an emotional level having served as a connected soldier and lost people. He protects himself by isolating, and that’s kind of where I’m at too. The antagonist/s in this story still see human networking as both inevitable and profitable, to the point of forcing it on people through a virus.

Why did you choose to distribute this as a full graphic novel rather than over multiple chapters?

Sable: This has always been a complete story to me. Not that there isn’t potential to more fully explore this world, but to break it up would have meant creating artificial cliff-hangers that I think were better used for more story.

Donaldson: I didn’t choose the OGN, the OGN chose me! I just like it better as a matter of focus and organization. I thrive on having the big picture and quantifying it. I make big inventories upfront, I number the locations, the exteriors, and interiors, and I even make an inventory of props like guns and vehicles. You have to be okay with being bunked down in your office for a long period before you do cons and promo. Verdict!: I’m not in a hurry to work serialized again. Just remember me every 18 months or so, please.

ComiXology Originals have the potential to reach audiences that don’t typically read comics. What kind of readers do you hope discover The Dark?

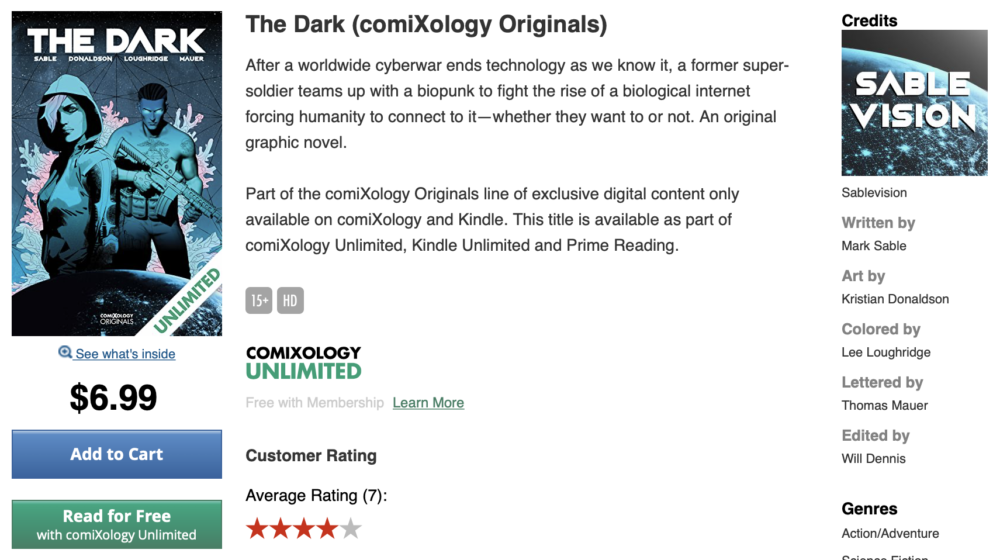

Sable: I’m still an every Wednesday, pick up my single issues from my local comic book store kind of guy. But there are digital-only readers who have never been exposed to my work, and it’s exciting to see them embrace the book. I saw the results of that immediately – in less than a week, someone showed me we were #1 in new releases in science fiction graphic novels. I never look at numbers but it blew my mind that we were beating Star Wars books.

ComiXology getting behind its Originals, showcasing them on their front page, making them free to Amazon Prime customers, and just generally making it easy for readers to read our work – that’s a really powerful thing.

But aside from the business side of things, I think there is something fitting about THE DARK debuting digitally. Kristian’s art is created entirely digitally and is optimized for the screen. And a graphic novel about the fall of the Internet distributed digitally…I couldn’t write a better scenario.

Donaldson: Everyone! Seriously. It’s been fun to turn on my “civilian” friends to the idea of reading a comic digitally, and you’re a few clicks away from it wherever you happen to be. Guided View rules and I’m glad to be putting work towards a platform that can continue to grow and adapt and reach people. If I were appealing to any demo directly it would be the Streaming Genre Film and TV person who likes comics as a thing but might not have read one in a few years. Like me!

Follow Mark on Twitter @marksable and Kristian on Instagram @kristian.work. The Dark is available now on ComiXology for only $6.99 or free with a subscription to ComiXology Unlimited.