The Toronto Comic Arts Festival is one of the most influential and important comic book event in North America. Its mission is to “promote the creators of comic books in their broad and diverse voices, for the betterment of the medium of comics”. In the spirit of this mission, The Beat has conducted a series of interviews with some of the phenomenal cartoonists in attendance at this year’s festival. We hope that these interviews will improve our understanding of these creators’ voices, techniques, interests and influences. Read on for our interview with Kat Verhoeven.

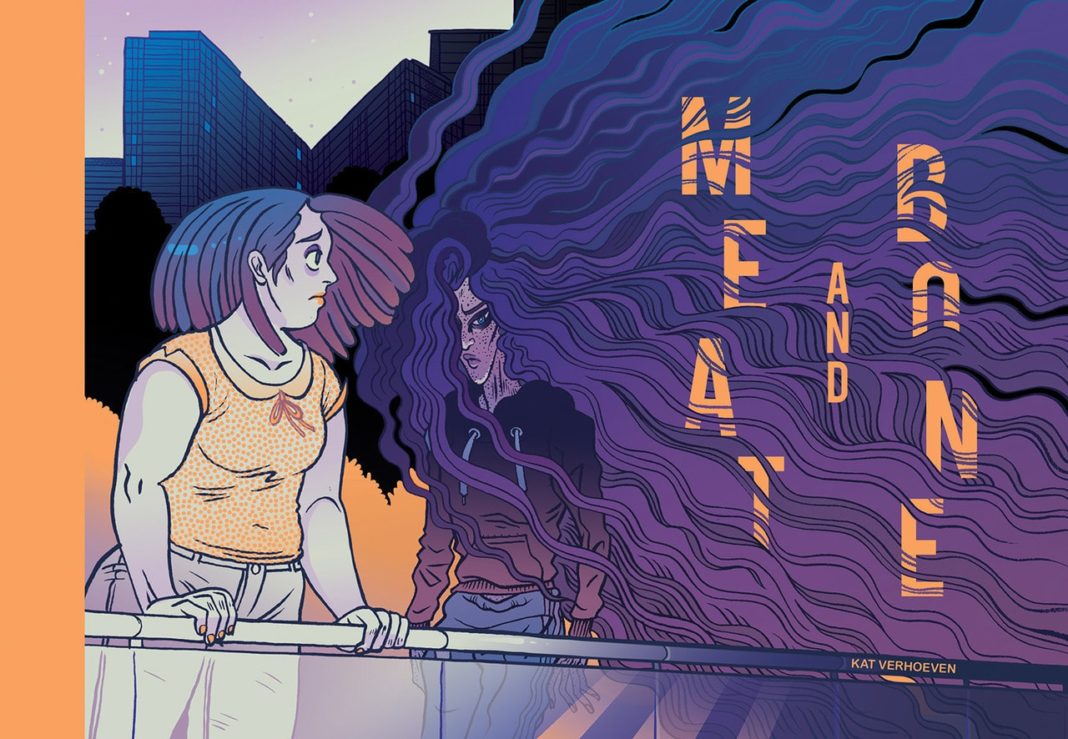

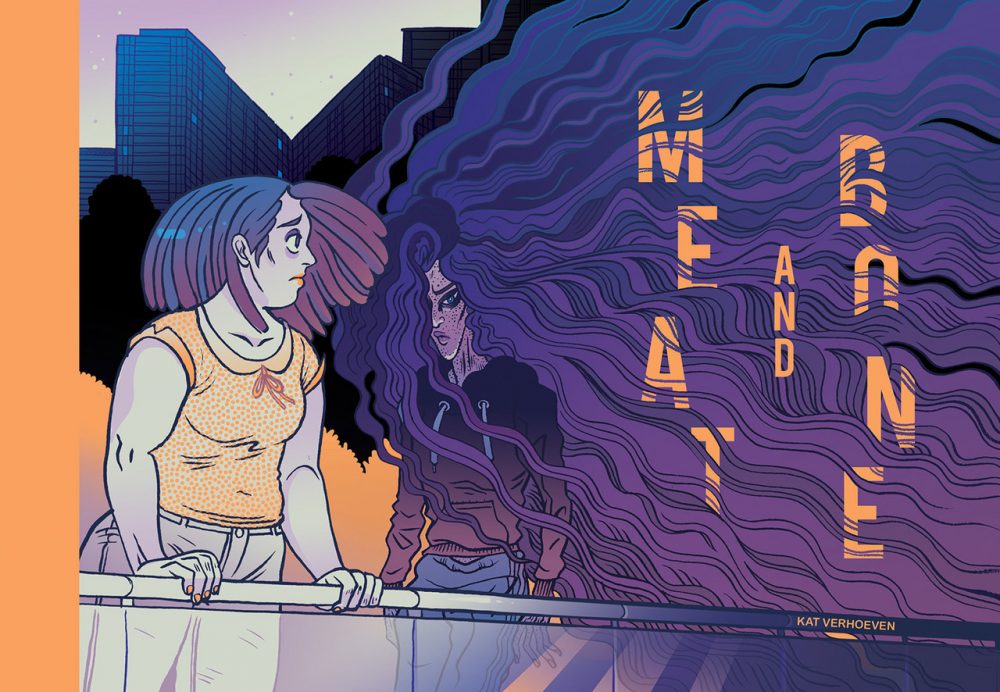

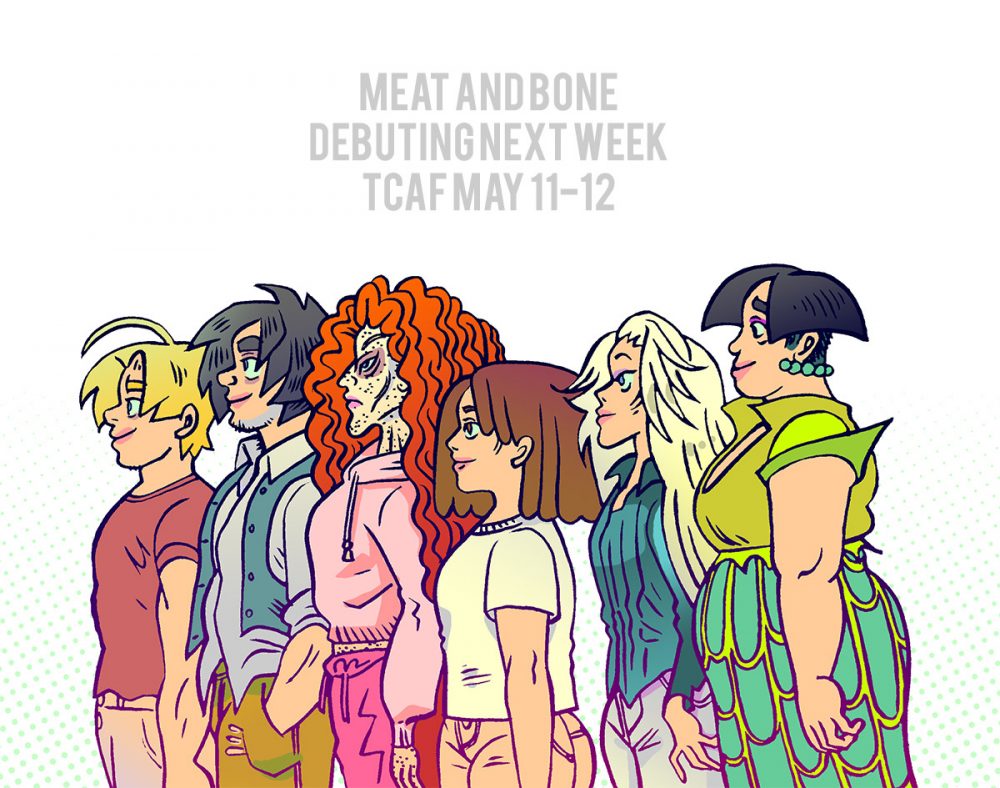

Kat Verhoeven is a Toronto-based cartoonist best known for her award-nominated graphic novel Towerkind and the long-running webseries Meat & Bone. Her work has a heart-warming quality that is quite touching. After a very long serialization online Meat & Bone is debuting at TCAF this weekend coming courtesy of Conundrum Press. Kat has gracefully agreed to chat about Meat & Bone and her short comic about self-publishing comics.

Philippe Leblanc: For those readers who may not be familiar with you and your work, can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Kat Verhoeven: Of course! I grew up in Eastern Ontario and eventually settled in Toronto, where I graduated from the Ontario College of Art and Design. I’ve traveled and spent a couple years couch-surfing, mainly in Canada, Australia, and the USA. I now work as an illustrator and at a printing press. I’ve contributed to several anthologies, web publications, and have made many zines ranging from abstract comics poetry to traditional narratives. I think I’m best known for my pocket graphic novel Towerkind (2015), which was nominated for several awards and initially ran as a serialized mail subscription comic. That was a lot of fun. I’ve been working on Meat and Bone since 2012.

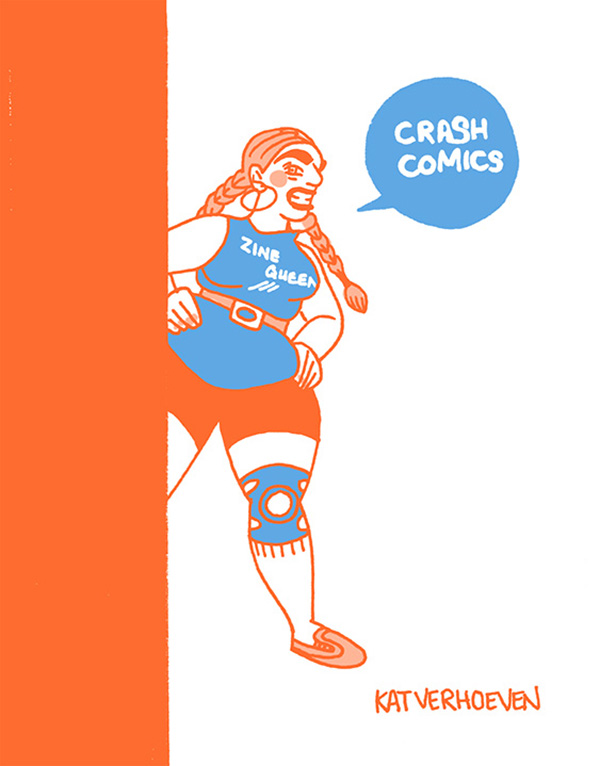

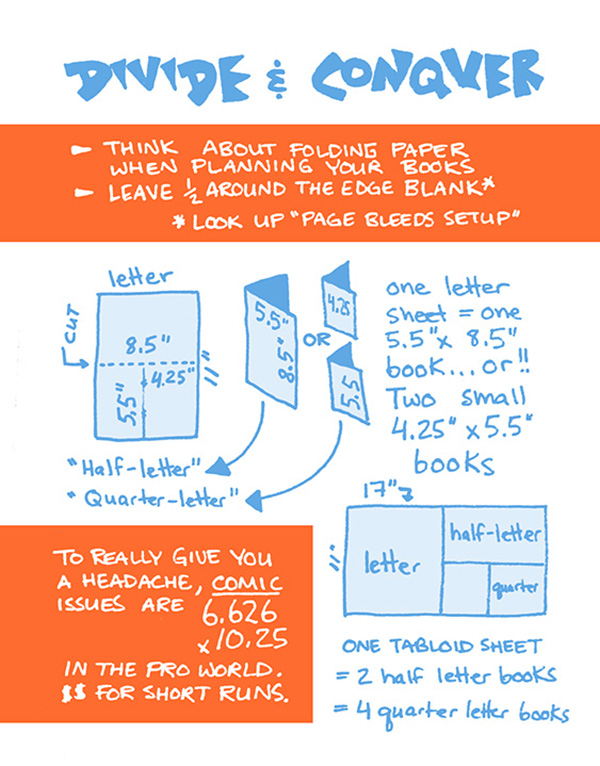

Leblanc: I’ll want to talk about your upcoming graphic novel Meat & Bone in a minute, but first, I wanted to talk about your zine Crash Comics that came out in 2015. It’s an intro to mini-comics, and zine making for beginners. You go beyond the basics of “how to write a story” and jump into the more practical elements of making comics, paper stock, binding, printing types, folding, file set-up and many other subjects. Why did you want to make this comic at the time?

Verhoeven: There’s so much information about drawing techniques! You can find anything you want to learn about technique quite easily now. I’ve helped organize a few zines, and have worked in the printing industry for several years, so I wanted to make it easier for people to print their books nicely, and there’s really a knowledge gap for basic things like standard paper sizes, or knowing what a gutter is and how to format it. People don’t know what the K in CMYK is (it’s Key). There’s a lack of vocabulary – I wasn’t even taught this stuff in school. I think technical things should be approachable, even if it might be less fun than learning to use Photoshop or ClipStudio tricks.

After Towerkind came out I was asked to do a workshop for youths through the Toronto Public Library. I wanted to guide that group through making a simple folded zine, but I also wanted to give them a resource for making more complex work later if they wanted to. I made Crash Comics as a giveaway for them. It’s now available for free online. I also recommend Let’s Print a Comic which is written by Rhiannon Rasmussen-Silverstein and drawn by Daisy McGuire. It’s an even more in-depth look at making comics.

Leblanc: Crash Comic was released in 2015. Now that we’re in 2019, do you feel like the ecosystem of self-publishing has evolved since then? Is there anything you wish you could change, or add to this work?

Verhoeven: I think that it still does a solid job as a quick primer, but there’s a lot I’ve learned in my work in the years since, both in cartooning and in printing. I know a lot more about offset and the internal organization of large printing presses, as well as new and emerging techniques and machines that change everything. You can foil at home now! Wild. Wish I’d made a page on that. There are a few small inaccuracies, but nothing big. Re-reading Crash Comics just now, I do cringe at suggesting China for offset. There are still local offset printers! There’s a price difference, but it can be manageable. I think it’s more important than ever to at least try local first, even if it doesn’t wind up being viable.

The digital section is, of course, outdated already. I’m glad to see I was looking ahead and made a note about how that would happen – thank you, Kat of the past. I wanted to make sure to keep a positive and uplifting tone in this book, which is complete with a ‘you can do it!’ pep talk. In reality, I’m more critical of the state of the arts. Comic making in Canada is really great, and Toronto is a good city to be in if you want inspiration, but the government has changed for the worse since 2015 and arts funding has been gutted. A lot of the resources I was so excited to point blossoming zinesters towards probably don’t exist in the same capacity now.

Leblanc: Meat & Bone started as a webseries in 2012. Conundrum Press is publishing the series as a graphic novel and is debuting it at TCAF 2019. How do you feel about seeing it come to life in physical form?

Verhoeven: Oh man, I’m exhausted. I joke that finishing a big comic like this gives you postpartum (no disrespect to actual moms, please indulge me my hyperbole), and I guess it’s true. I’m really proud of it, and it’s very surreal to hold it and look at it. I’ve already read this book over hundreds of times, but it feels different to see it physically. Maybe I’m not exhausted, maybe I’m elated.

As I worked online to an update schedule, and made physical zines on the side, I kept thinking to myself ‘the way I write is really meant for books’, and I still feel that way. Meat and Bone was only an okay webcomic. My pacing, formatting choices, drawing style, my everything is suited to a single sitting read, to splashy spreads and a toothy paper texture. This is how it was meant to be.

Leblanc: You describe Meat & Bone as “the story of Anne, her roommates, and Marshall, the mysterious girl downstairs. It’s four women’s stories about eating disorders, relationships, food, polyamory, and above all else relying on your friends”. Did you know how long this series would last back then?

Verhoeven: Not at all. I had a bullet list and a fondness for reading serialized webcomics that never stated their endings. I thought I would do that too, until I’d covered all the talking points I wanted to dig into. It only took me about 70 pages to realize that is just not how I work. I can’t write something open-ended indefinitely. An attentive reader will probably notice a big shift in tone around that mark, because I completely changed how I was working on the story. Lots of chaff got thrown out. I like to layer my ideas, and knowing the ending lets me work back and forth.

I think I started out wanting to make Octopus Pie but I ended by wanting to make Meat and Bone.

Leblanc: There are some elements that seems autobiographical but the story is definitely a narrative fiction. How did you reconcile those two elements, the autobiographical and the fiction?

Verhoeven: A lot of the main plot points and some characters traits come from what I was doing and struggling with, or seeing in my close friends when we were all in our early twenties. I had an eating disorder, probably (there’s a line Anne says about her doctor dismissing any possibility of her having an eating disorder, and that’s lifted directly from my doctor). I’m not very comfortable with making straight autobio comics. I don’t like letting people look into my life that clearly, or understand how people like Lucy Knisley do it so well. That’s a lot of vulnerability even when you’re not talking about starving. I wanted to talk about things that I hadn’t seen in comics and that were hurting me, but in a way that was interesting, safe, and hopefully engaging for people to read. Have no doubt, this is very much a story.

As I worked on the script, the characters grew into themselves. By the end of Meat and Bone there is very little of the source material left, the people I based my characters or some of their traits on. I suppose as far as reconciling the two aspects of it goes, having a clear idea of what I want to say and knowing who my characters are guides me more than the autobiographical elements in making a strong character drama. Or maybe I just don’t see those two things as being at odds.

Leblanc: There’s also the recurring presence of Jane Fonda, someone who was quite vocal about her own eating disorder. Why was it important for you to include her presence in Meat & Bone?

Verhoeven: Having the Jane Fonda references started as a throwaway gag where Anne wants to be as sexually desired as the frequently ravished and ravishing Barbarella, which I decided I liked visually enough to turn into a reoccurring dream and theme.

I had bought the Jane Fonda Workout Book myself, and read her foreword about having an eating disorder and how that affected her, which helped me decided to write Meat and Bone in the first place. She’s an iconic person, though I don’t think younger people know about her legacy, and Barbarella as a character isn’t as prominent in the public consciousness now as she has been in the past. Maybe the reference is idiosyncratic with the rest of the comic, but having Barbarella sequences has let me have playful fantasies in an otherwise serious story.

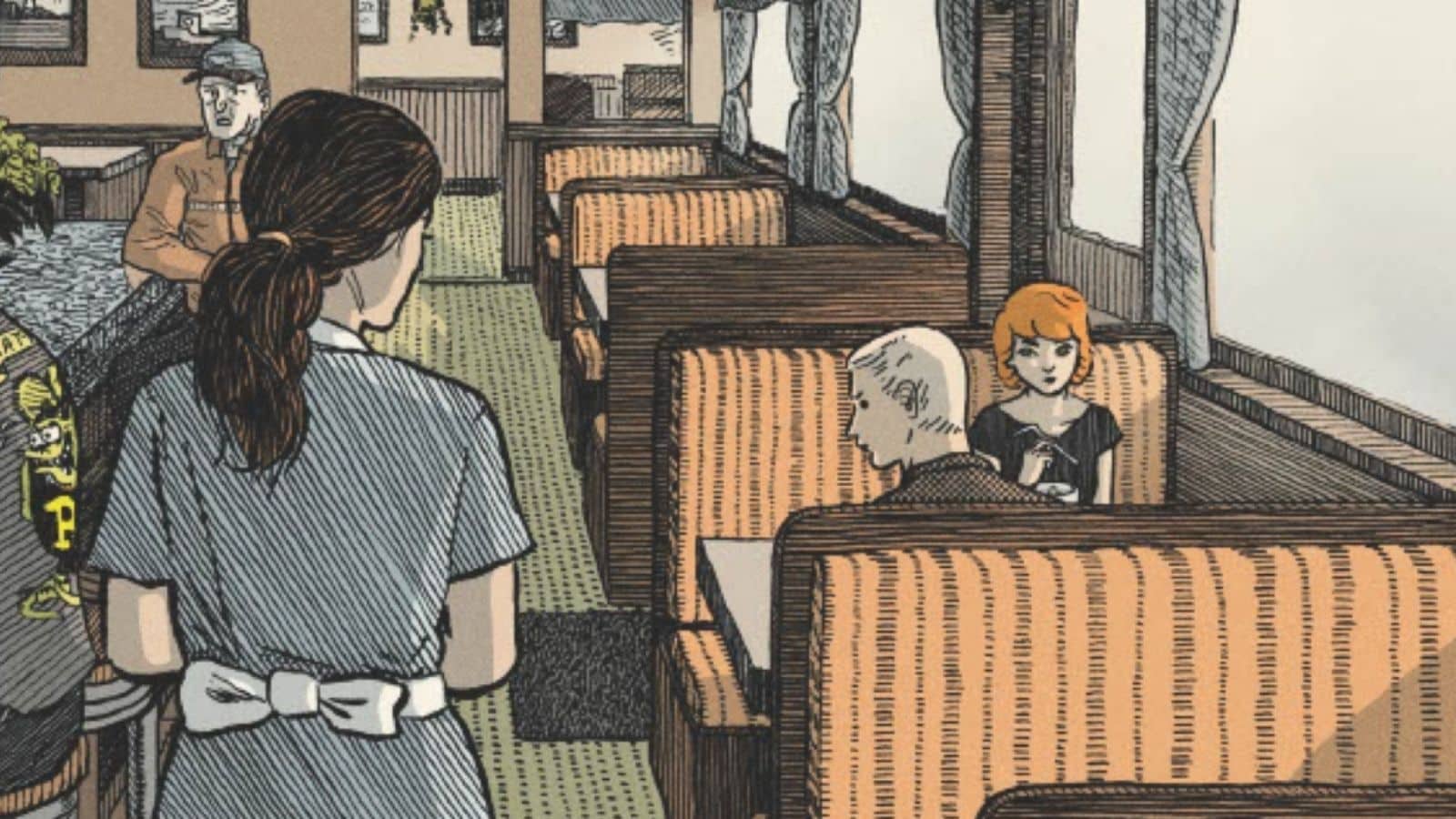

Leblanc: Your story centers on Anne and Marshall, but it’s also brought to life thanks to the importance of the people around them in their life. It’s a technique you’ve used for Towerkind too, using a large secondary cast to show your story using multiple perspectives. How did you juggle developing all of your characters when making your story?

Verhoeven: I let the characters develop organically with time, and as needed to move the story. For example, Priam’s big reveal wasn’t planned from the first page.

Some characters were originally meant to have smaller roles, but many were actually meant to have full story arcs that got cut when I decided to write an ending instead of run a serial. Despite that, I hope no one comes off as stilted, I want everyone to have a distinct silhouette and personality. I do find that working with large ensembles lets me show all the angles of a characters personality as different types react differently to and play off one another. Anne wilts around Gwen but blooms around Jane.

That idea is also at the heart of Towerkind. No one is strong enough on their own to be their best self or to do what they have to do – I think that’s one of those lessons that I have to learn for myself over and over again, so I’m always retelling it even when I don’t set out to.

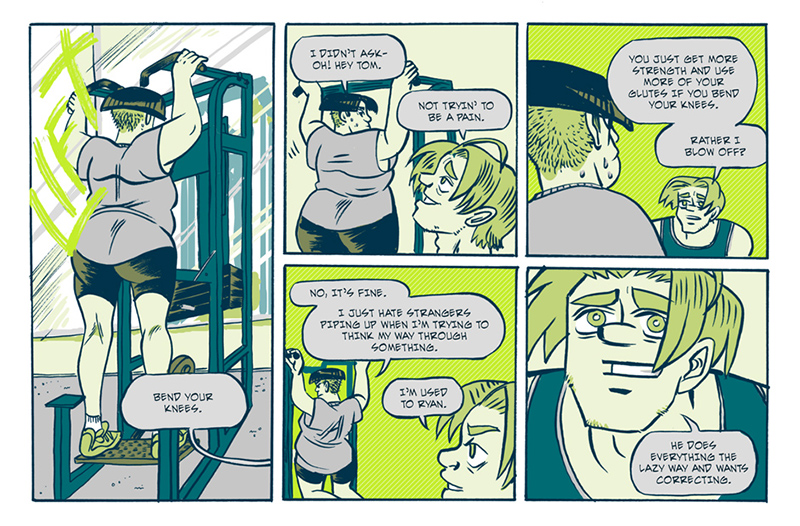

Leblanc: I love the colours of Meat & Bone. It starts with a single-colour scheme and eventually switched to full-colour vibrant tone. Did you change anything for the print edition of the series? Could tell us a little bit more about your colouring process?

Verhoeven: There are some huge changes, and I hope people who’ve been following from the beginning of the webcomic, and even those who read is all online before the site came down to promote the book, will notice! I’m really excited about some of this. I moved sections of the comic around for greater cohesion (Jane arrives at the beginning instead of mid-way!), and better pacing, patched the artwork, and made a short new intro. I did leave a lot of the original artwork. Seeing the progression of style and skill over the years is part of the appeal of reading a project like this.

Around the end of the online run I had to focus on just getting the comic out on time, so I dropped colouring altogether for those uploads. When I finished those pages up for the print run I made some of what I consider my strongest palettes to date. I love colouring, but I’m not very interested in colouring rules or norms. So long as a panel reads and has clarity, I’m much more concerned with conveying a mood with the tone of the colours than in keeping a character on-model throughout the story. Anne is a brunette, but there are scenes where she’s a redhead, strawberry blonde, blue-haired. Marshall’s red hair is a huge element in the comic, but I made it blue on the cover! Why not?

My process isn’t very special. I look at a bunch of different colour palettes that I’ve been saving over the years for inspiration, think about the tone of the scene and see what feels right. With that in mind I flood my most important areas and work backwards until it all gels. I use a lot of gradients and some limited shading and highlighting, but I don’t like over rendering.

I did once have a rule against using either black or white. I adhered to that for several years as part of my learning process. It forced me to think very differently about the values I choose tot communicate light and dark. I’ve let white back into the mix now, but black is still banished.

Leblanc: What do you want readers to take with them once they’ve finished reading your comics?

Verhoeven: If someone finishes my book and it gives them a greater appreciation for their friends and the people supporting them in their life, and the will to support others, well. I can’t think of a better compliment.

You can find Kat Verhoeven’s comics on her website, read Crash Comics, and get some info on Meat & Bone. You can also follow her on Twitter, Tumblr & Instagram.

You can come meet Verhoeven during TCAF. She’ll be at table 155-156 with Conundrum Press on the main floor. She’s excited to talk to you about Meat & Bone.