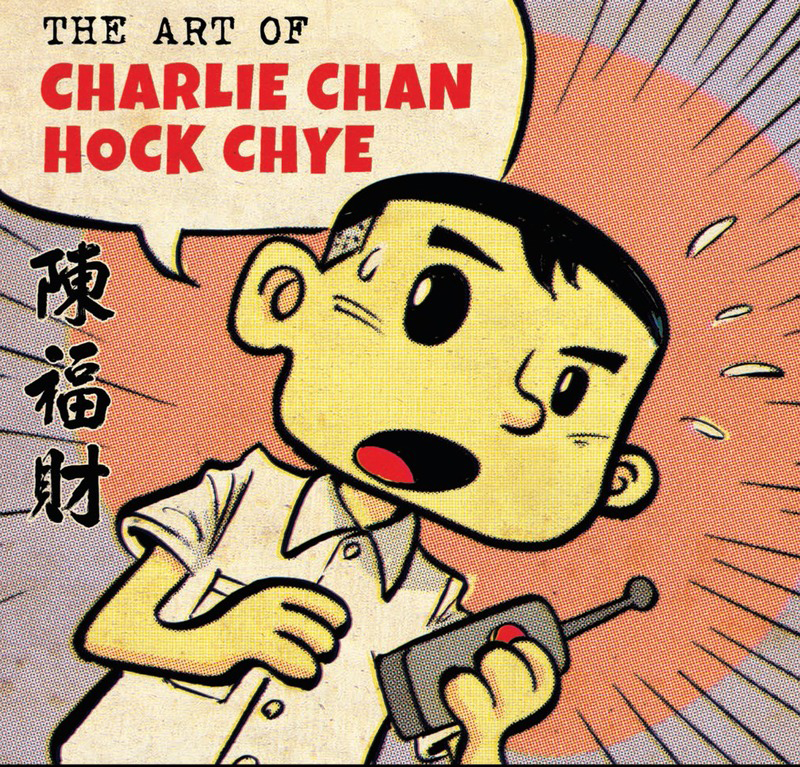

During the bustling Saturday of NYC’s MoCCA event, Sonny and I sat down behind the cramped Pantheon Books booth to chat about The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye – Liew’s new graphic novel recently published in the US discussing Singapore’s tumultuous history after WWII through the work of prolific Singaporean cartoonist Charlie Chan Hock Chye.

All images used are either by or of Sonny Liew.

Comics Beat: Something I found really interesting that I didn’t know about The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye – maybe I misread something – was that he was not a real person.

Sonny Liew: [Laughs] Yeah.

CB: How did your approach the early stages of this book? Was it always going to be the subject matter framed through the lens of Charlie or did it change over time?

SL: It started with a book I was reading called Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History Of Comic Art by Roger Sabin. I was trying to learn more about comics history, and I realized that you couldn’t separate comics history from cultural and political history, which provided the background information on the motivations behind a creator’s work, or helped explain why a genre was popular. For example, Robert Crumb, whose early work was closely tied to the counter-cultural revolution of the 60s.

So I thought that if you flipped that around, telling the history of Singapore through a fictional version of its comics history, that might be a really interesting way to structure a book. At that point I’d wanted to create whole generations of fictional cartoonists, but when I started doing it I realized that would be a little too unwieldy – so the focus got narrowed to just one artist.

CB: What was the process of weaving Charlie’s history into an established history? How did the events and cartooning styles you wanted to show come into play?

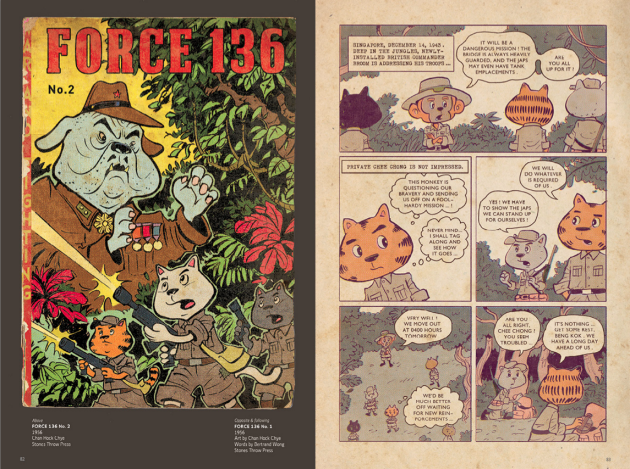

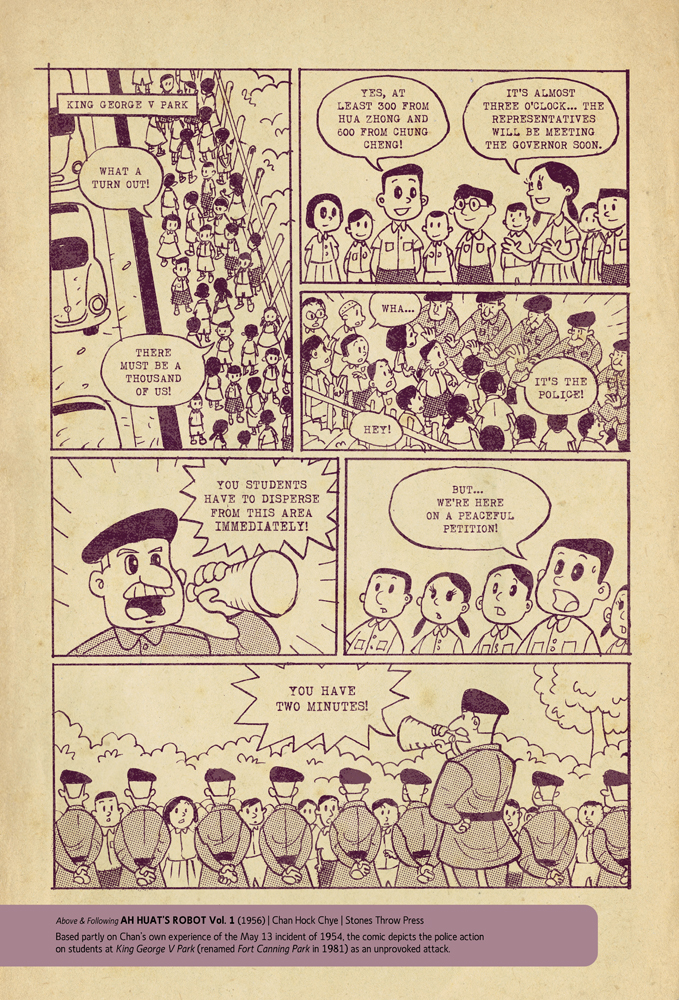

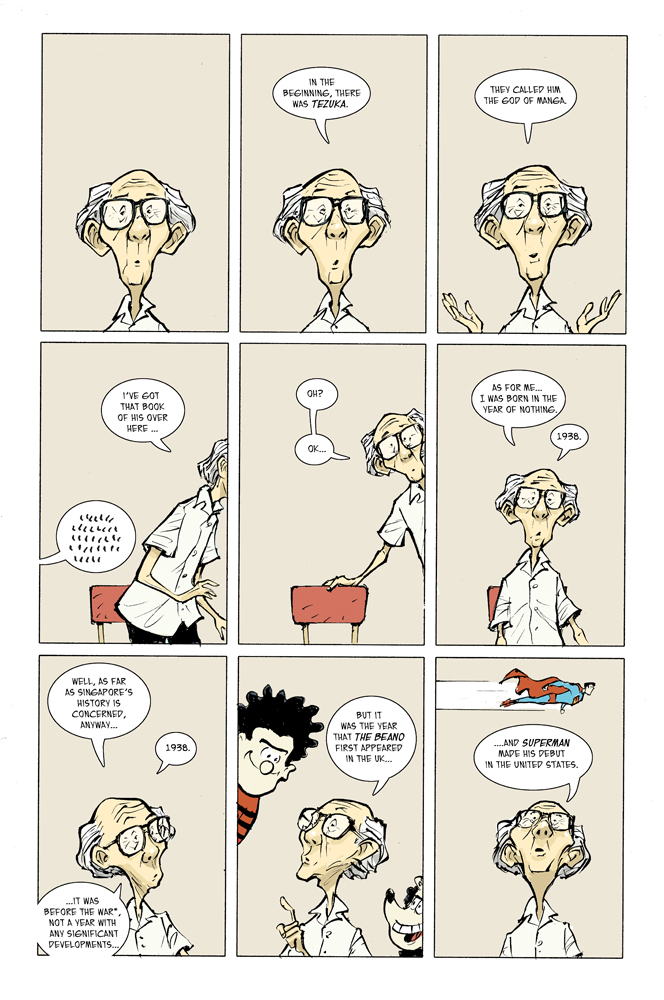

SL: I mapped out a timeline of Singapore’s history alongside major comics works and creators. For example, I would look at the year 1961, when Marvel came out with Fantastic Four and juxtapose it against what was happening in Singapore at the time. Aside from a chronological matchup, you also had to find the stories and styles that would fit the narrative needs. Like the section about Malaysia and Singapore’s merger and separation– to me, the politicking involved had an air of childishness about it, so Peanuts or Pogo seemed like plausible vehicles. I picked anthropomorphic animals in the end because they seemed to provide the right flavor to the narrative.

CB: I definitely saw personality and attitude traits conveyed through what animal was representing what figure’s position in history.

SL: Yeah exactly, it was all about finding the right fit between things.

CB: I’m always interested in seeing the path of influence in comics – how you learned to tell the stories you want to tell, but in this case, as someone who didn’t know Charlie was fake while reading, I felt that you considered Charlie a huge influence in your own work.

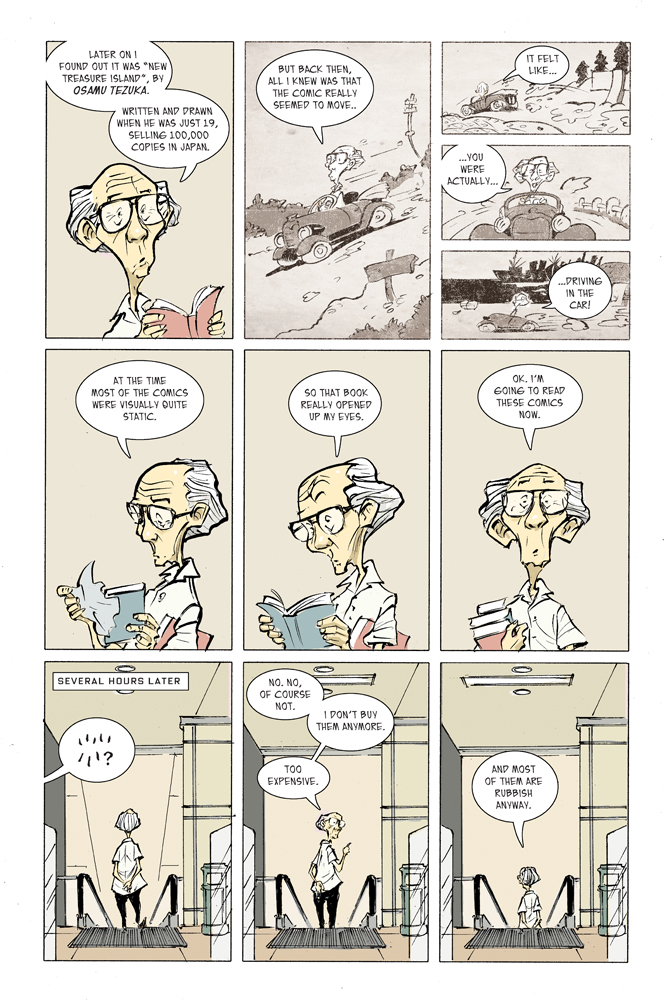

SL: Well, there’s something to that since his life is based on a lot of creators I’ve admired and been influenced by, like Wally Wood and Osamu Tezuka.

What’s odd is that since the book’s been published, Charlie Chan has become more “real”, as though he’s taken on a life of his own. Maybe that’s because once you finish a book, it does become a thing in itself, and you start to be able to see the characters in them from a distance.

CB: What’s really fascinating for me is that it seems like, if one were to glance and his career path and yours, it’s almost like you’re creating the footsteps you’ve followed and if I had to map your “trajectory” it would be to Charlie’s.

SL: I’ve heard that before, yeah. Maybe true to the extent that when I was doing the book, I was sort of at a crossroads in my own career. Despite the work for publishers like First Second and Marvel, I hadn’t quite figured out a way to do my own books, where I got to do both the writing and drawing. So the Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, was sort of a moonshot, a Hail Mary pass that I hoped would get me to a place where I could do more personal work and still get some sort of reasonable moolah for it.

CB: Yeah, you gotta own your work.

SL: Yeah, yeah. So it was that was a period of draining the savings, and hoping things would work out.

CB: If it’s any indicator of “success,” I would mark the publish of Charlie Chan the split between his and your paths where you’re living out the dreams that he had – coming to the US and people lining up to buy his comics.

SL: [Laughs] Yeah, I can see that angle.

CB: I’ve been saying that I didn’t know Charlie wasn’t real, but I had an inkling because of the drastic shifts in his style. What was the thought behind having his style directly reflect the influences instead of having a more “cohesive” evolution?

SL: Well in my own mind, that was partly about raising question about the nature of Chan’s work. The fact that he, in a way, copied a lot of styles, to me, was a hint that he wasn’t as original as he though he was. To create a sort of tension between how good he was and how much of a copycat he was. On one level you could blame various external forces for his failures, but it adds to the complexity of things if you raise doubts about the quality of his work too.

CB: Is that a fear you attribute to yourself a little bit?

SL: A little bit, yeah. Doing this book, I thought about people I was influenced by like Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, and Chester Brown and I wondered how much of it felt original and how much would feel too derivative. And of course you always worry about things like “what if I’m just not good enough?”

CB: Yeah, that’s the thing about making comics – it’s still kind of a small environment and influence is easy to spot. Doesn’t make it bad though.

SL: Yeah, maybe we can call it “appropriation”?

[Both laugh]

CB: Along those lines, how was it to exercise or “appropriate” those style in history to represent Charlie doing just that?

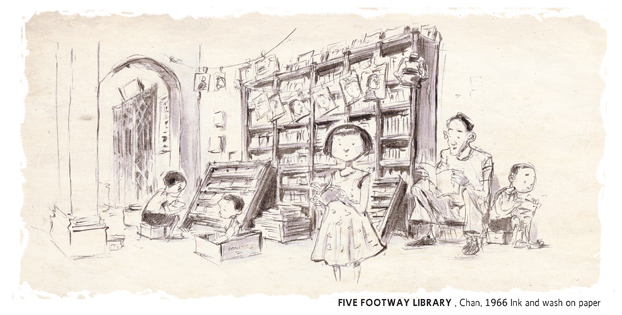

SL: I was very nervous going into each new section because let’s say when I was finishing up with the Tezuka stuff and moving onto the next part – I would have no idea if I was going to be able to pull it off. I usually stayed nervous until the first two or three pages emerged, then I felt like I was on safer ground. For the really early childhood drawings, I actually drew with my left hand so the linework would look convincingly naive. For the Tezuka stuff I used nib pens for the first time, just so things would come out looking a bit more raw.

CB: A common thing that I’ve been told that I didn’t know before doing creator interviews is the amount of learning that happens while doing a book. I definitely had the misconception that creators are as good at something going into a book as they are coming out.

SL: No no…well sometimes. I guess if you’ve been doing something for a long time like the same comic for 10 years maybe you do reach a certain plateau. Otherwise there’s always going to be a learning process, maybe even a steep curve.

CB: Would you say there was a primary style to Charlie Chan?

SL: Probably the sections where I’m drawing Charlie Chan at various ages, or the scenes depicting modern day interviews with him. Those pages help to anchor the book visually, provide some continuity. Initially I wanted to do stick closer to the Art book format with pictures and essays but I realized pretty early on that the nature of actual Art books meant you seldom read them in a linear fashion – they were coffee tables books you dipped into at random points.

I wanted to find a way to compel the reader to read the book from start to finish, so what Scott McCloud did with Understanding Comics, or Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor suggested themselves as models for a way of, well, seducing the reader into following the story from beginning to end, and I replaced the essays with comics, which unfortunately meant a lot more drawing was required.

CB: I’ve always struggled with books about comics that aren’t in comic form, the dissonance bugs me.

SL: No one really thought of it before Scott McCloud, that’s the funny thing.

CB: Getting back to the foundations of Charlie Chan, I’m curious about your personal relationship with Singapore. You were born in Malaysia but moved to Singapore at a young age?

SL: Yes, when I was young my parent sent me over for my studies.

CB: And then you came to school in the US?

SL: The UK and the US, yeah.

CB: The question I’m getting at is how are Charlie’s critiques of the Singaporean government from you or more reflecting the sentiment at the time?

SL: Well, clearly the book reflects my own thoughts and ideas to some extent, but I also tried my best to see things through Charlie’s eyes – to imagine a plausible perspective of someone in his position. It was important that Chan wasn’t just a mouthpiece for me, that he was believable character.

There are parts where he consciously identifies himself with Lim Chin Siong and for me that was a way of raising question about how much of Charlie’s admiration for Lim were about political ideals versus finding comfort in a shared sense of failure, to be able to blame external forces for not reaching your dreams.

CB: I suppose in some fashion, that’s a way of finding peace when looking at a life’s work.

SL: Yeah, we all need to find ways to make out lives make sense to ourselves.

CB: Jumping gears a bit, you worked on First Second’s Shadow Hero with Gene Yang and you’re currently working on DC’s Doctor Fate with Paul Levitz. Though you aren’t credited as the writer on them, I feel there’s a connective thread between the two.

SL: Oh yeah?

CB: Yeah specifically the empowerment of first-generation immigrants. To me, these stories help show the wide spectrum of perspectives available to the status of “immigrant”.

This is a bit of an abstract way to get to it, but when you were studying in the UK and US, how do you think those experiences have influenced the themes in you work?

SL: I became a lot more aware of issues of race. The population in Singapore is mostly Chinese so being in the US and UK was when I had firsthand experience at being a minority. When you’re part of the majority, a lot of times the whole fabric of the world around you is so much in your favor that you never think about it, you take things for granted. And then you get to the US and people would drive by and yell “chinky chong” for no reason. What the hell, right? Most of my Asian friends in the US and UK had at least one or two of these experiences – just random encounters with racism.

That made me a lot more aware and that’s one reasons I wanted to work with Gene on the Shadow Hero. Even back with My Faith In Frankie, I’d asked Mike Carey to let me draw Jeriven as an Asian deity. It didn’t really alter the script in any fundamental way, but for me it was at least a gesture towards diversity. So being in the UK and US definitely made me more away of these issues. If I had stayed in Singapore, I’d probably have just drifted along thinking, “everything is fine”.

CB: So Charlie Chan experienced some pushback in Singapore when a government grant for creative work was revoked after the book’s completion. What has the reception for Charlie Chan been like in that context?

SL: Well, the National Arts Council (NAC) decided to withdraw the publishing grant for the book after they took a closer look at the book, for supposedly undermining the authority of the government. It was worrying for a while, given how wafer thin book profit margins can be. But then the news broke on social media, and we got a ton of free publicity for the book, and we sold a lot more copies than the publisher had ever anticipated – some 8000 copies at last count.

CB: Everyone wants to know what’s going on, huh?

[Both laugh]

SL: At the same time, I’m sure there are people who’ve refused to pick up the book because they’re pro-government and assume that it’s a subversive tract. And schools below the tertiary level might be much more wary of recommending it to students. But I’ve been really glad that many who have read it see it as a labor of love, an attempt to tell a more inclusive story about Singapore.

CB: Were you surprised or disappointed by the withdrawal of the grant?

SL: Well…yes and no. When the publisher first applied for it, I’d wondered if they NAC would think it was too politically sensitive. But once the grant was awarded, I didn’t imagine they would revoke it. The grant process is supposed to be quite objective, with both external and internal reviewers – it goes through several stages of review before approval. So I’d assumed they knew what Charlie Chan was about.

As far as I can tell, what happened was that the NAC had seen some of my more commercial work and pegged me as someone who just wrote whimsical stories about street urchins and giant robots. When they say the book itself, they went “hey, wait a minute…”

CB: Trying to pull a fast one, weren’t ya?

SL: [Laughs] A ten-year long con it was. So yes and no when it comes to being surprised.

CB: Knowing very little about the Singaporean government as it currently stands and peoples’ perception of it, it sounds like living in the country is overall good, but like any government I suppose, the history is complex and often not so great. Do you think it could benefit to being more open to transparency?

SL: I think a lot of us believe that the ruling party in Singapore has earned enough political credit to be be more open about things. Look at car prices in Singapore as an example – a form of taxation means a Toyota Corolla that costs 20k in the US would set you back 75k in Singapore. I don’t see many other governments in the world being able to impose a system like that and not getting into trouble. Yet its been something Singaporeans have accepted as part of the package of good governance.

So the ruling party’s achievements maybe earns them the credit to admit to past missteps, to be more transparent and inclusive about Singapore’s history. The barrier I think is in their own ideology – the need to tell their version of the Singapore Story is so woven into who and what they are, so much part of their DNA, that they feel compelled to stick to their guns come what may.

CB: The contextual perspectives represented in Charlie Chan about Singapore’s history is something that I never would have gotten out of conventional history schooling. Do you know if there are plans for Pantheon to push the book to schools in the US?

SL: I don’t know if that’s part of their plans, or if that’s something schools are open to. I’ll suggest it to them though!

CB: Is this sort of political and historical work the kind work you want to continue doing?

SL: I think that these issues of politics, economics and history can be explored in comics in interesting ways, and its something I hope to be able to do. The worry is really how to approach the next book without making it too similar to the Art of Charlie Chan. That’s been I worry about; to do something that’s interesting but somehow different and not a repetition of old narrative forms and gambits.

CB: You did the Tezuka “Hitler” book, now it’s time to do the [Shigeru] Mizuki’s “Hitler” book?

SL: Oh, that’s an interesting thought….

CB: Considering the themes and subject matters of the stories you’re telling or getting hired to tell, are afraid of getting pigeon-holed or type cast?

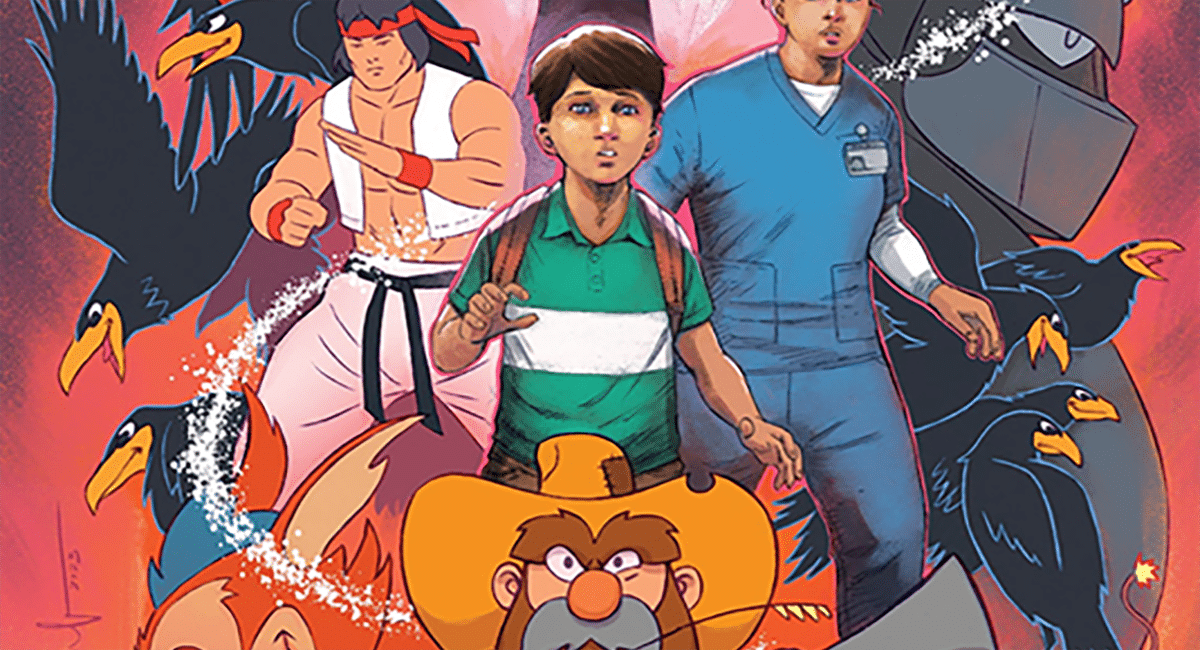

SL: I think I was a little more worried about it a few years ago, when my work was often described as “whimsical”. I’d done the Jane Austin adaptations and Wonderland, and it felt like I was being pigeon-holed style-wise. But I think with Shadow Hero, Charlie Chan, and Doctor Fate maybe people are more open to me doing different things now, even the superhero stuff with capes and explosions.

CB: How did Doctor Fate come to be then?

SL: I think it was mostly due to the Shadow Hero. [Paul] Levitz had seen my work with My Faith In Frankie but never thought about me a potential superhero artist until he saw the Shadow Hero. So he suggested my name to DC and things were set in motion.

CB: Thank you so much Sonny.

SL: Thank you too, Zach.

Sonny Liew lives in Singapore and makes comics. He’s known for his work on DC’s Doctor Fate with Paul Levitz and First Second’s Shadow Hero with Gene Luen Yang. His newest released work is The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye from Pantheon Books.

Comments are closed.