The Beat’s Gregory Paul Silber has been accused of having a bit of an… obsessive personality. Each week in Silber Linings, he takes a humorous look at the weirdest, funniest, and most obscure bits of comics and pop culture that he can’t get out of his head.

Earlier this week, Marvel studios dropped a trailer for the upcoming Disney+ streaming series She-Hulk: Attorney at Law. As with any live action adaptation of a Big 2 superhero comic these days, it was immediately met with heated discourse from in and out of the MCU fandom. Some praised the lighthearted tone, comparing it favorably to beloved legal comedies like Ally McBeal. Others criticized the special effects, as Jennifer Walters (Tatiana Maslany) looks notably less lifelike in her She-Hulk form than her He-Hulk cousin, Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo), in the same show. And I’m not even going to touch the debate over whether Maslany is appropriately buff for the super-strong, 8-foot tall, green title character.

Mostly, I’ve been thinking about how nice it’ll be to get a show or movie about a superhero who doesn’t have a tragic origin story for a change.

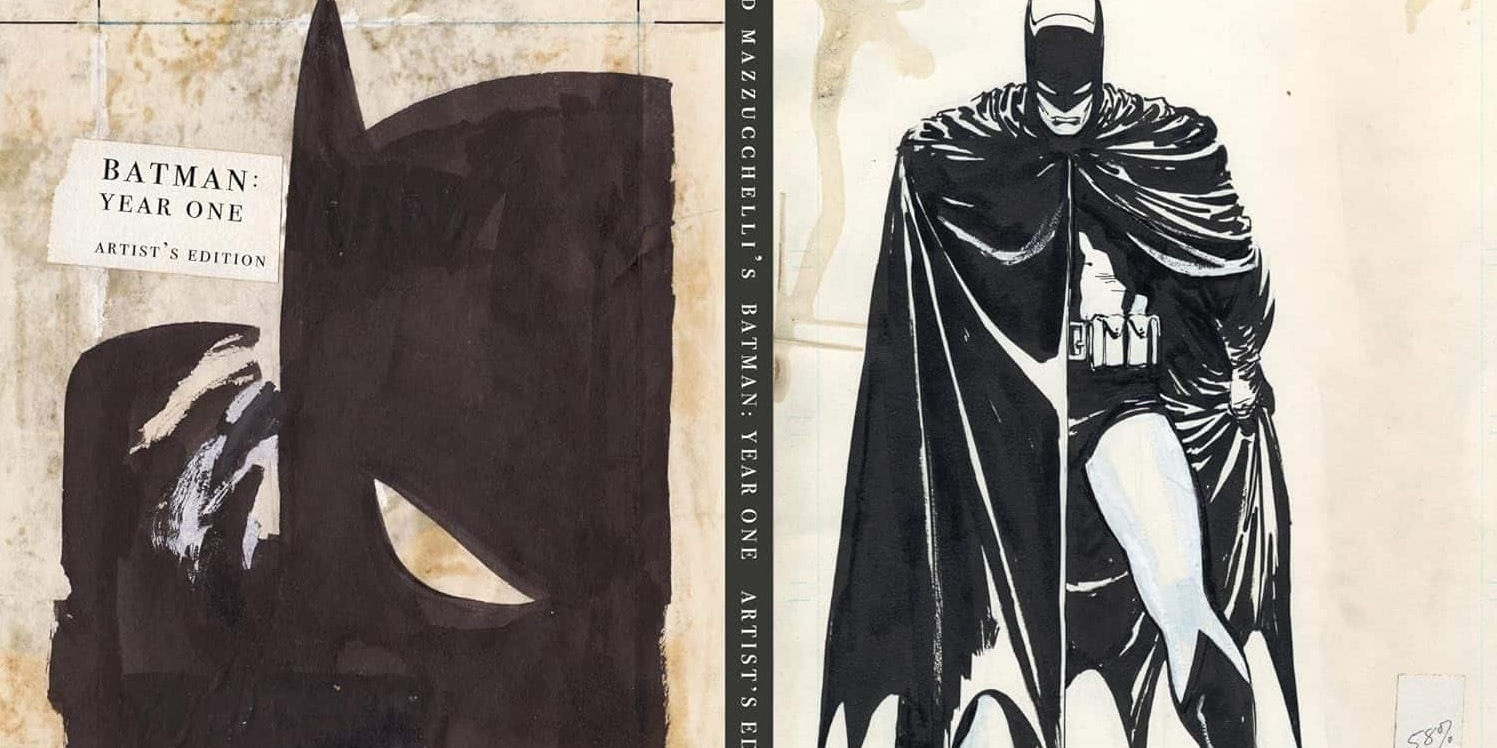

Before I get into why that’s so appealing, let’s be clear that there’s nothing inherently wrong with the tragic origin as a trope in superhero fiction. It’s used so often because it works. A key part of the fantasy of superheroics is the fantasy of overcoming great odds. We love Batman because after suffering the violent death of his parents as a child, he sought to work towards a world where no other child has to feel the same pain. We love Spider-Man because Peter Parker works through his guilt over the death of Uncle Ben by honoring his uncle’s legacy and living by the principle that “with great power there must also come great responsibility.” We love Superman because Clark Kent is a refugee from a destroyed home planet that he can no longer return to, and now devotes his incredible power to showing kindness to the people of his beloved adopted planet.

But if the heroes of your fictional universe all have tragic origin stories, it creates the (unintended, one assumes) implication that heroism must be stoked by tragedy, and that nobody reaches that level of selflessness without something terrible happening to them or a loved one first. So that’s where characters like She-Hulk come in: superheroes who aren’t driven by trauma, but an innate desire to do extraordinary things for others.

That’s not to say it’s all been sunshine and roses for She-Hulk since debuting in 1979 courtesy of writer Stan Lee and artist John Buscema. Like literally any other character, you couldn’t have She-Hulk stories if nothing bad ever happened to her. It’s just that overcoming tragedy isn’t a core feature of her characterization. As a result, She-Hulk comics tend to be relatively lighthearted fare, and certainly when compared to her tortured male cousin.

This distinction even manifests in the way Jennifer Walters and Bruce Banner Hulk out. Ever since Bruce was exposed to that gamma radiation, his life has been a mess, and he’s usually desperate to find a way to rid himself of his Hulkness. Bruce’s Hulk alter-ego is either id-driven rage with a mind not unlike that of a toddler, or on some occasions, intelligent but cruel. Jen, on the other hand, can still function like a relatively normal (if green and freakishly tall) adult in her She-Hulk form. Not only can she speak complete sentences while Hulked-out, but the transformation makes her more confident and outgoing, hence why she often shows up to court that way. Outside of her work as an attorney, Jen’s She-Hulk form also makes the otherwise-shy Jen more willing to dance, party, and hook up with hot dudes – something else that the show appears to be leaning into, if the trailer is any indication.

But there are many other superheroes who lack a tragic origin, and the lack if darkness at the heart of their characterizations manifest in a variety of ways. Take Kamala Khan for example, the newish (she debuted in the pages of Captain Marvel in 2013) Ms. Marvel. Created by writer G. Willow Wilson and artist Adrian Alphona, alongside editors Sana Amanat and Stephen Wacker with a design by Jamie McKelvie, much of the discussion surrounding Kamala has focused on her Pakistani-American identity, as well as the fact that she’s one of the few Muslim superheroes of any prominence in Marvel comics and comics in general. That’s important; everybody should be able to see their identity represented in a superhero, whether we’re talking about ethnicity, religion, sexuality, gender, or anything else that shapes our life experiences. Hell, as a Jersey boy myself, I appreciate that Ms. Marvel comics, which take place primarily in her hometown of Jersey City, are among the few positive representations of New Jersey in media – stay away from her, Kevin Smith!

But mostly, the reason I think Kamala Khan is the best superhero created in the 21st century so far comes down to her relentless optimism. Kamala comes from a loving family, and while she occasionally butts heads with her parents and brother like any teenager would, they’re supportive and, crucially, alive. She struggles with social anxiety like many geeky teens do, but she has a tight-knit group of friends who are all – and I can’t stress this enough – alive. In the earliest issues, Kamala’s superhero origin moment didn’t come from the death of a loved one or anything else similarly traumatic, but a more interior conflict. Kamala, who idolizes Carol Danvers – the first Ms. Marvel, and current Captain Marvel – found herself trying to become someone she’s not. She became the hero who she was meant to be when she embraced being herself.

Ms. Marvel is a great character because she can’t help being anybody but herself. She’s giddy anytime she meets another superhero, aggressively compassionate, and unafraid to look a little silly. After all, her cartoonish “embiggening” powers that allow her to create an oversized fist to punch bad guys with or extend her legs by several stories so she can walk from Jersey City to New York City through the Hudson River, look pretty ridiculous, but that’s part of her charm. While we’re on the subject, it’s a shame that the upcoming Ms. Marvel show on Disney+ is giving her an entirely different power set, but at least Kamala’s personality appears to be intact.

While the happiness at the core of Kamala’s characterization certainly stands out in a sea of miserable heroes (said with love!), even before the debut of She-Hulk the idea of a superhero without a tragic origin was hardly a new phenomenon. Barry Allen, the longest-tenured Flash since debuting in 1956 courtesy of writer Robert Kanigher and artist Carmine Infantino, did not originally have a tragic origin. If you watch The Flash TV show or have seen the Justice League movie, you may be familiar with a version of Barry who’s driven to solve the mystery of his mother’s murder, but that’s a relatively recent invention. The retcon was introduced in the 2009 comic miniseries The Flash: Rebirth by writer Geoff Johns and artist Ethan Van Sciver, which followed Barry’s return to life in the DCU decades after he died saving the universe in Crisis on Infinite Earths. One might argue that that event was the tragic origin of Wally West for his tenure as The Flash, but Wally was Kid Flash for decades before that and didn’t have a tragic origin before, so I don’t think it counts.

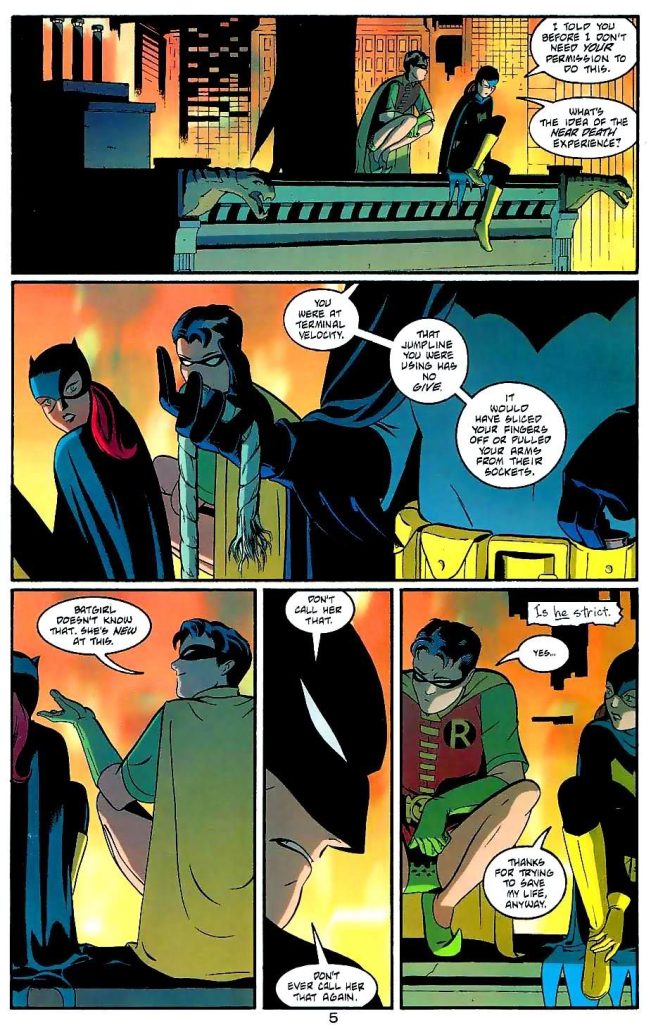

Anyway, as much as I’ve enjoyed a lot of Flash comics that have come out since the retcon, giving him a tragic origin where he never needed one before misses the point. Tim Drake was done similarly dirty when his father was killed off in 2004’s Identity Crisis by writer Brad Meltzer and artist Rags Morales. Tim’s origin as the third Robin was borne not out of his own tragedy, but Batman’s when Jason Todd, the second Robin, was murdered by The Joker. Until Jason was resurrected (comics!) in the mid-2000s, Tim never knew Jason personally. Therefore, Tim’s efforts to discover Batman’s secret identity and convince Bruce to take him under his wing was motivated by a desire to help his hero out of a rut, not to mention an innate heroic streak of his own. That Tim already had a loving, living father at home helped him stand out from Dick Grayson and Jason before him. Why go out of your way to take that away from him?

I have a similar bone to pick when it comes to one of my favorite superheroes, Barbara Gordon, the longest-serving Batgirl who also spent a few decades as Oracle. If you’ve only read one Babs story, it was likely 1988’s Batman: The Killing Joke by writer Alan Moore (who has expressed regret for the story and has since “disowned” it) and artist Brian Bolland. That’s the story where, among other things, The Joker shows up at Barbara’s front door and shoots her through the spine, paralyzing her from the waist down. The Joker then kidnaps Barbara and sends images of himself torturing her to her father, Commissioner Jim Gordon, in an effort to torment the man to the point of insanity. It’s even implied that The Joker may have committed some kind of sexual violence against Barbara.

I know a lot of people like that story and I’m not trying to shame them for it. I used to like it myself. Even at his worst (by his own admission!), Moore knows how to tell a compelling, unforgettable story, and Bolland is definitely in the top tier of comic book artists. But while I’m not interested in relitigating a controversial story that other critics have already argued about at length, it is a bit disheartening to think about The Killing Joke‘s stature in the canon of Bat-family comics considering how much it contrasts with what Babs represented before that.

Barbara Gordon was the daughter of Commissioner Gordon who simply decided to become a superhero. The boldness of that decision is a huge part of why I like her so much. She never sought permission from Batman to adopt his symbol, nor did she care if he objected to her activities until he somewhat-begrudgingly accepted her into his inner circle. And she certainly never told her father. One of my favorite secret identity dynamics in comics is between Babs and Commissioner Gordon. In my headcanon – and I’ve read comics that implicitly support this theory – Jim actually knows that his daughter is Batgirl, but he doesn’t say anything because he knows nothing he says would stop her anyway. There’s a sort of arrogance at the center of the superhero archetype, and few represent that as joyously as Barbara Gordon.

That’s not to say there wasn’t still joyousness after an unnecessary tragedy was added to her characterization. As Oracle, Babs was one of the few disabled superheroes, and in retrospect, putting her back in the Batgirl identity by allowing her to use the lower half of her body again was a regression. But even then, creators like Gail Simone made it work by leaning into the optimism Babs has been defined by since the 1960s.

There are many ways to tell a superhero story, and my love of superheroes without tragic origins isn’t a value judgement against those who do have tragic origins. But the magic of the genre is in making the reader feel like they can be heroes too. Nothing horrible needs to happen to you to become a great hero. All you need is a desire to do good for others… although who’s to say that gamma radiation exposure won’t help too.