Horror cinema has a long and conflicting history with misguided representations of queerness. Despite some glowing examples of how to do queer horror right, LGBTQ characters have often ended up serving vindictive evil, standing in as the dark Other, or even becoming the unlucky victims of some of the most vicious death scenes in movie history. Shudder, the AMC-owned horror streaming channel, already has an excellent documentary tackling the genre under some pretty similar circumstances in Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror. In light of its success, which has been resounding and truly a step forward in terms of visibility for black horror, Shudder has announced a new documentary dedicated to queer horror, which will be written and directed by Sam Wineman (The Quiet Room).

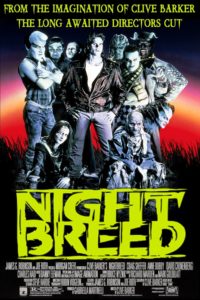

The documentary is currently untitled but will follow Horror Noire’s structure closely, offering a history of queer horror that will stretch as far back as the movies of James Whale (whose The Old Dark House is considered one of the gayest films of the 1930s) to movies like The Hunger (1983), Heavenly Creatures (1994), and the recent Netflix hit The Perfection (2019).

These two strands of queer horror, of which there are more, are fertile ground for an exploration of empowerment and agency in spite of being a part of a problematic film tradition where queerness is mostly seen as evil and ugly. I’m not saying queer characters aren’t allowed to be evil, but a more balanced and diverse playing field, with queer creators both in front of and behind the camera, would make for a richer horror scene.

It’s also important to recognize just how text, subtext, and context affect our reading of these movies. As is the case with the films explored in Horror Noire, many of the films under the queer horror banner are very much products of their time, social attitudes and misconceptions included. It will be interesting to see how the new documentary accounts for evolution and adaptation throughout the history of queerness in horror.

We are currently witnessing a stronger and more imposing push towards newer and more innovative forms of horror in queer cinema. If the announcement of a new queer horror documentary, coupled with the previous success of Horror Noire, is any indication, expect a whole series of documentaries from Shudder looking at horror from a variety of perspectives. And the voices that come from these other places, these other groups, have some terrifying stories to tell.