By Ani Bundel

The concept of “public domain” is one fans have heard a lot but know little about. Intellectual property rights for famous characters and stories vary from country to country. But as one of the world’s entertainment capitals, U.S. law tends to overshadow them. Technically it’s 70 years after the death of the creator. But due to companies (mainly Disney) lobbying to extend those expirations, for many of us, works entering the “public domain” hasn’t happened in our lifetimes, until last year when the Sonny Bono Copyright Act, which froze all copyright protections for 20 years, finally expired.

That isn’t to say fans haven’t found workarounds. The rise of internet fan-fiction can be traced to the inability to use characters, as the restrictions dragged on. But thankfully, the Bono Act was not re-upped in 2019, and works have started entering the public square for the first time since the end of the 1990s. This sudden change in the landscape inspired San Diego Comic-Con’s Sunday afternoon panel “Public Domain Comics: From Sherlock Holmes to Mickey Mouse and Beyond.” It was a lively discussion concerning works that have been public domain for a while and those who will finally enter it after being restricted for many decades.

Malibu Comic publisher Dave Olbrich led the conversation. He was joined by publishers Tom Mason and Barry Gregory, along with entertainment attorney Michael Lovitz, specializing in trademark and copyright law (He also founded the Comic Book Law School®).

The conversation around public domain comics began with Sherlock Holmes, most stories of which was already in the public domain before the 1998 shutdown. Olbrich and Mason discussed how there was an attempt (by them) to reproduce the Holmes stories as comics — not new stories, mind you, but a faithful reproduction — and found themselves facing a cease-and-desist from the estate. Even though the stories may be in the public domain, the owners (or former owners) will find ways to extract a fee anyway. As Lovitz explained, loopholes like trademarked images or licensed characters exist. So even though there’s a real celebration about new works becoming free to use, there are always pitfalls creators should look out for.

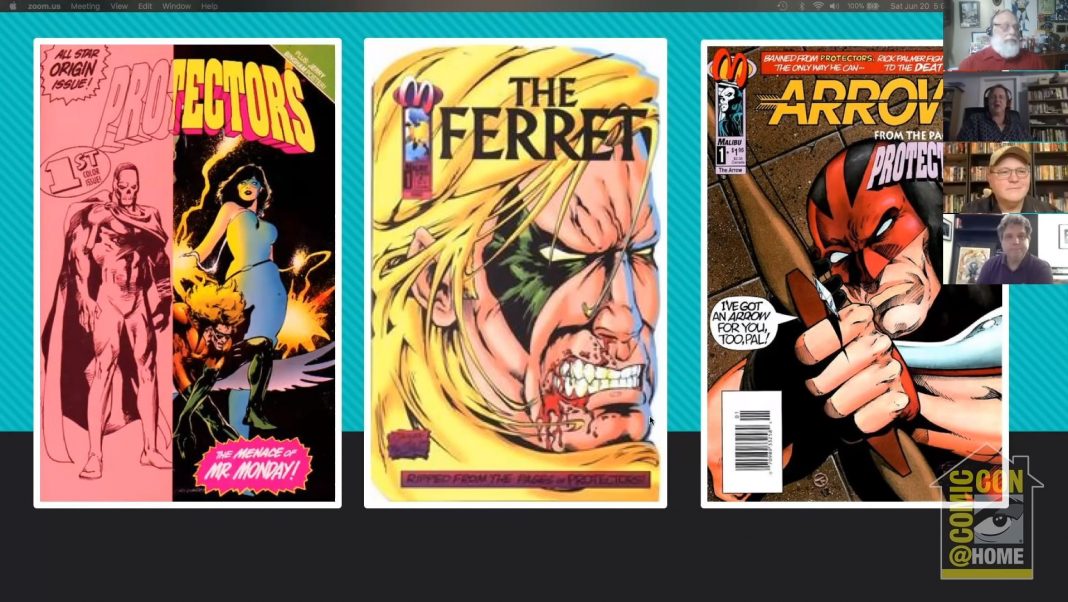

And there’s also the need to face down that a lot of what passes into public domain is usually very dated. Unlike Disney stories, which seem to be remade and reused and sequel-ized (partly to keep them from moving into the public domain), these are stories that have remained static. Mason regaled the panel of how much work went into bringing back The Protectors in a comic, which meant hiring a historian to research every character. They then went character-by-character discussing what can and can’t be used, what was “too problematic” to keep and what could be given a modern twist.

Lovitz’s advice to anyone looking to get involved in using the new stuff starting to enter the public domain was to do your homework. Estates will come after you, but that’s doesn’t always mean they are right. He cited one case where the Arthur Conan Doyle estate tried to claim Holmes was protected because of stories written in the 1930s, and the court ruled against them. Once the first story passed into the public domain, then the characters were free to use, period.

Even with the work involved, this is an excellent time for creators, as more and more traditional media comes available. Some of the works created in 1924 that will become available this year are classics, such as Paramount Pictures’ 1924 Peter Pan and Henry Otto’s Dante’s Inferno. There are several novels, including E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, and songs like Rhapsody in Blue, first performed in a 1924 concert titled “An Experiment in Modern Music.” Fans can’t wait to see what creators do with them.

Miss any of our other SDCC 2020 coverage? Click here for much more!

Respectfully, Ani, you seem confused.

The Sonny Bono Copyright Act didn’t expire. It changed copyright terms from 75 years to 95 years (for works of corporate authorship). It didn’t “freeze copyright protections for 20 years”; it extended the copyright term by 20 years. Works from 1923 had previously been set to expire in 1999, but that expiration got pushed back to 2019.

The Bono Act is still in effect. Corporate copyrights still last 95 years. Individual copyrights still last life plus 70 years. This has not changed. Copyrights got extended by 20 years, and then 20 years passed and so those copyrights started expiring.

I also don’t really buy the premise that the rise of Internet fan fiction is a result of copyright extensions. Fan fiction predates the Internet significantly, and there’s lots of fan fiction based on recent works that would still be under copyright even under the old 75-, 56-, 28-, or even 14-year terms.

As for Sherlock Holmes, you’re not quite right there, either. The 6 Holmes stories that are still under copyright in the US were written in the 1920s, not the 1930s (the last Holmes story Doyle published was in 1927). And “Once the first story passed into the public domain, then the characters were free to use, period” is not an accurate summary of the court ruling in that case. Only the elements that are in the public-domain stories are free for use. You can’t incorporate characters or story elements introduced in those last 6 stories until they enter the public domain.

Your last paragraph is wrong too; you use the future tense to describe “works created in 1924 that will become available this year”. Copyrights expire on January 1. The headline of the article you linked is “The books, songs, films, and other works entering public domain on Jan. 1, 2020.” As the headline implies, all the works listed in that article entered the public domain at the beginning of this year. 1924 + 95 = 2019. 2019 ended and their copyrights expired. The next round of expirations will be January 1, 2021, when copyrights from 1925 expire.

Everybody makes mistakes, but this article makes a lot of them, and it really should not have been published in this state. There’s already a lot of misinformation on the Internet about copyright. We didn’t need more.

“Fans can’t wait to see what creators do with them.”

I’m not being a smart-aleck when I ask, do what? I understand Disney used public domain fairy tales as part of his creative journey, but nothing much else comes to mind as worthy of attention.

What would I do with “Rhapsody in Blue” – change the notes? Put it in a soundtrack of my action-adventure movie? I don’t get all this excitement. Even the great Alan Moore couldn’t do much more with public domain characters than turn them into porn actresses. Which is where so much of this ends up.

Guess I’ll have to watch the video.

Comments are closed.