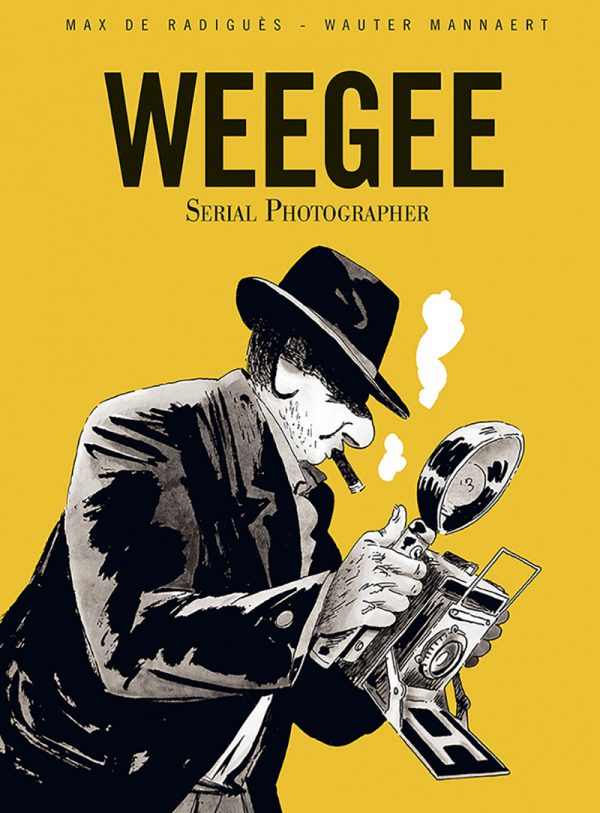

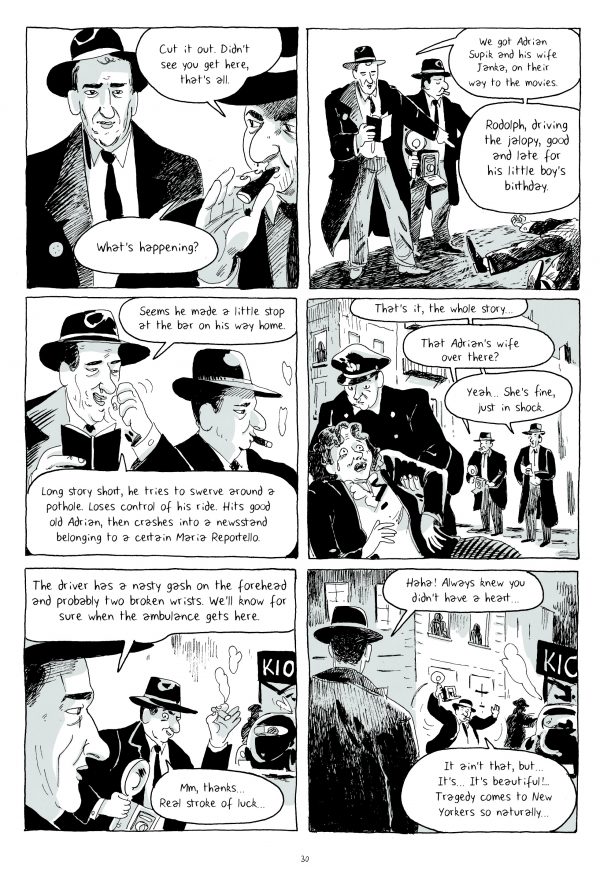

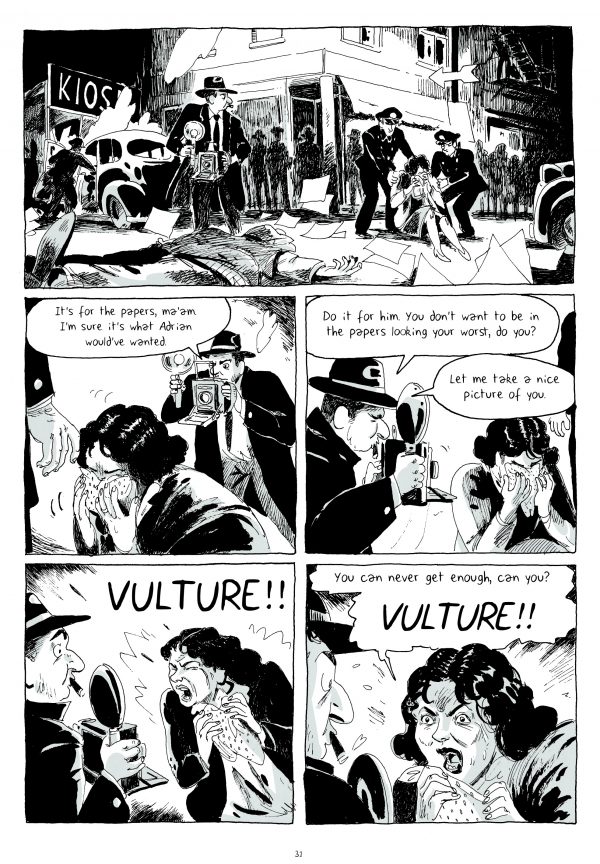

Let it be said upfront that in this more enlightened time, legendary photograph Weegee is not the kind of person that is given a lot of sympathy. He is, to put it in current vernacular, “problematic.” His most famous period of work, the period covered in this biography Weegee: Serial Photographer, had him combing the twilight streets of New York City in order to capture the lurid sights that gave that city its jolt of thrill, while also repelling the people who were attracted to that jolt. People, particularly women, particularly immigrants, were, in context of his photos, objects meant not just to exoticize the darkness of the city, but proclaim himself the master of it. It’s the kind of urban porn that is now frowned upon.

But historical figures are typically problematic, particularly artistic ones, and to dismiss Weegee because of this aspect is to refuse to look at a strain of American culture that extends to this era. Our obsession with true crime podcasts, the vast array of reality TV offerings, and the disturbing rise of YouTube stars, Instagram stars, and whatever other desperate self-promoters you find online, they all reach back to Weegee and his era.

Max de Radigues seems to get this, but he also understands that part of the lure of Weegee is the time in which he practiced his trade. Watching some teenager on YouTube monetize his monologues is not as exciting as seeing Weegee wade through the dark muck of humanity, with only his flash piercing the night to reveal a corpse that would, to the rest of humanity, remain a secret note of our worst aspects. There’s a romance to this, and if superheroes existed in the real world, they would probably be a lot less like the Watchmen and a lot more like Weegee.

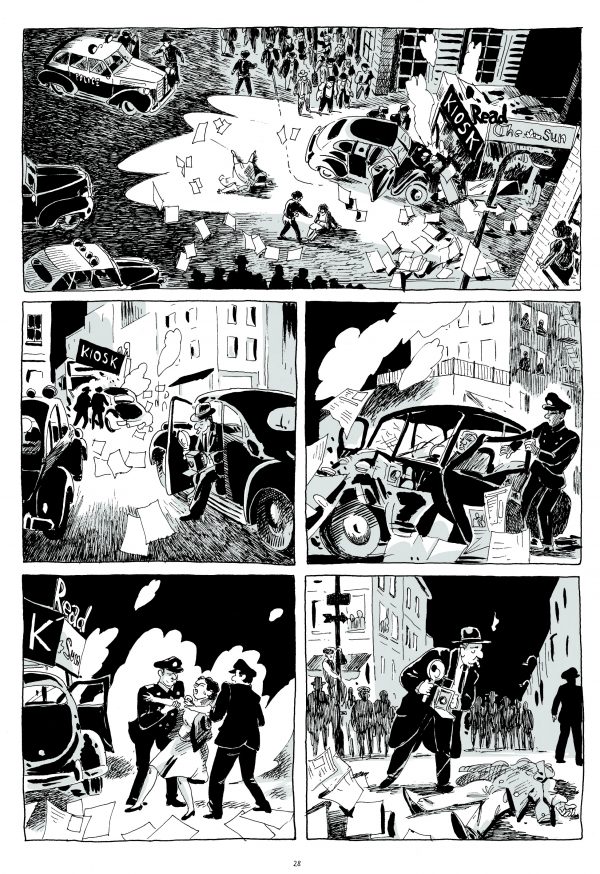

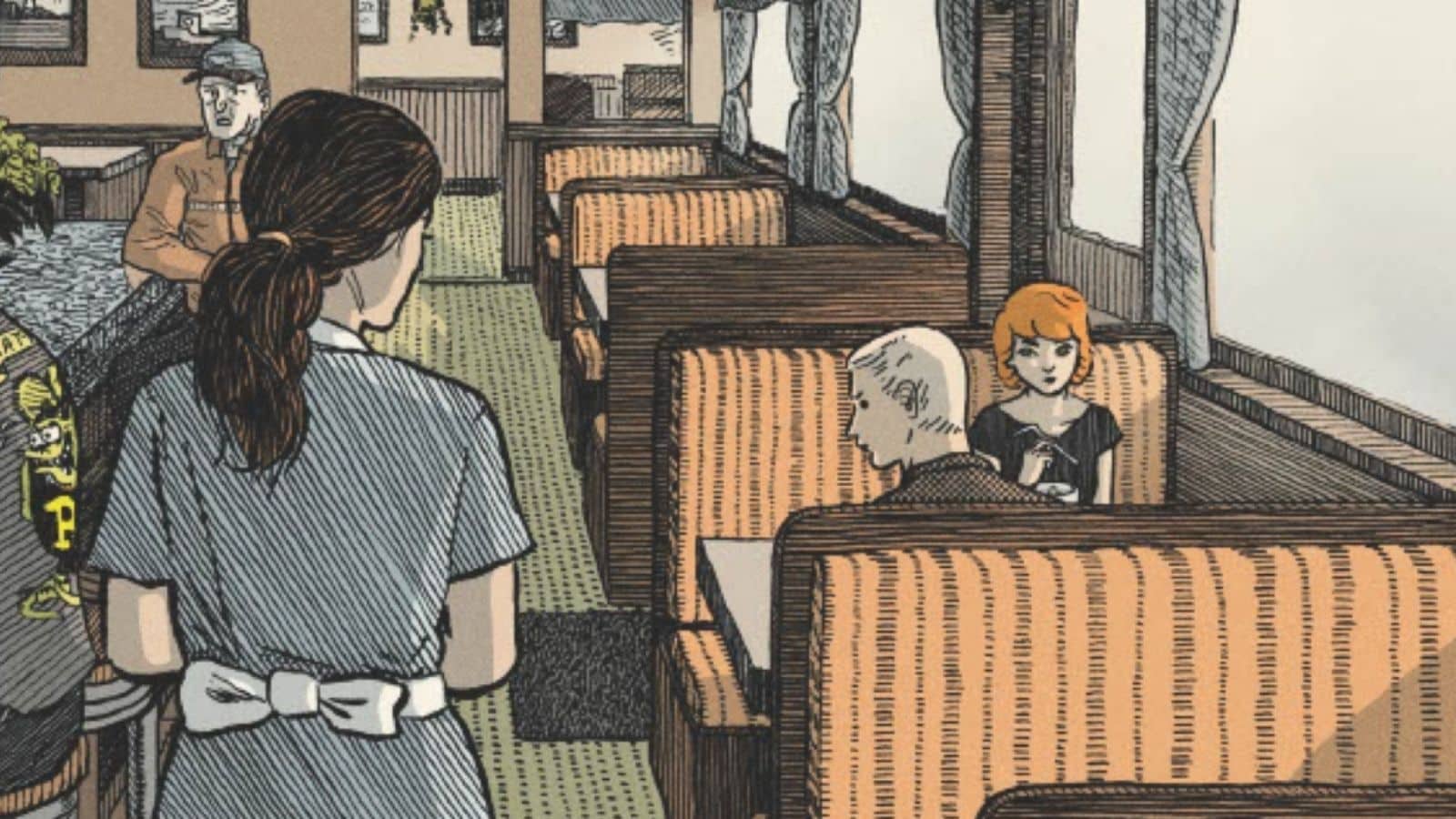

Weegee is our world’s Batman, a self-serving herald of a gruesome, raunchy world hidden to many of us, especially in the 1940s. Our superhero doesn’t solve crimes, he exposes them. He has no rogues gallery, he just drinks at the same saloon. In the visual presentation, de Radigues and Wauter Mannaert gets this beautifully — his depraved twilight New York City is one of brutal beauty and a kinetic energy that makes you understand why Weegee sped around with his camera. Who wouldn’t want to do that in the city as presented by Mannaert?

But there’s a conflict at the heart of Weegee. Well, several actually. One is that his preoccupation with the tragic, the grotesque, the pathetic haunts him in his unconscious, unleashed in nightmares that question his own complicity in this culture of violence and inhumanity that Weegee documents.

Another is his own desire for a higher station in life. An immigrant living in the Lower East Side, it’s both an understandable and typical goal. But like that jolt of thrill I mentioned, Weegee is both invited into that more reputable world and turned away from it. He sneaks in, but he’s a permanent outsider there. Part of that is because he is genuinely incapable of being anyone but himself. Part of that is because the stench of the world he brings functions merely as a novelty to the inhabitants of the world he’s trying to enter.

And then there’s the conflict that affects us all—fake news, really. Many of Weegee’s photographs of true crime and city scenes contain staging. Fictional elements. They are part truth. They portray a pure truth that reality sometimes doesn’t. In this way, Weegee is the spiritual ancestor of filmmaker Werner Herzog, though Weegee was partially well-honed identity based on a real one, not entirely the person he actually was, but neither what he presented to the world. But what has this routine combination of fiction and fact brought us? Fiction is reality? Reality is fiction? Everything is a mix? Can we trust our own eyes or even our own brains? Has this been going on so long that we can’t tell the difference anymore?

The story of Weegee is ultimately a tragic one because it’s the story of a person who denies who he is. Weegee moves on from the street photography and never quite finds himself in the same way. But that’s probably what he had to do to get through life. The horrors he faced in the streets of New York City, and the cynical approach he took to capturing them, couldn’t possibly have gone on forever. The worst part about the ugly side of life is the realization that its been going on forever and probably isn’t going away any time soon.

Weegee is all of us and we are all “problematic” in our own way, because we all sometimes find ourselves qualifying the ugliness in unsympathetic ways just to get through this universe, and we all need to turn away eventually to save our own soiled souls. That’s just the human condition and Weegee makes us look at that.

What an interesting book! Worth a read, by the looks

“Problematic” is an interesting word in its current usage. I’m reminded of how “The Accused” was hailed as an important masterpiece when it was released. It shined a light on rape and male entitlement in regards to sex. But today the movie is a Pro-Rape Male Gazer masturbation exercise, showing Jodie Foster to be a woman-hating rape-defender who wants men to watch as women get gang-raped one after another. Why hasn’t Foster been blacklisted yet?

Really, I was getting more of a Nightcrawler starring Jake Gyllenhaal type of vibe to the usage of the word porn. Similar theme, different period and documents in time

“But today the movie is a Pro-Rape Male Gazer masturbation exercise …”

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered such a misinterpretation of a movie. When you get a movie as wrong as “Jimmy Threeballs” did, I seriously doubt he’s even seen it. Or he saw it and had no idea what it meant.

Strange that a man calling himself Jimmy Threeballs would be full of shit. You learn something new every day.

Comments are closed.