“Apparently you can get 3G up by the stone circle,” a mother tells her son, summing up the central point of existence in the 21st Century. A stone circle, thousands of years ago, was a point of invisible contact with unseen forces beyond human comprehension. Now it’s still a point of invisible contact with unseen forces, just more mundane than before. Or maybe not. Maybe it’s the exact same level of mundane.

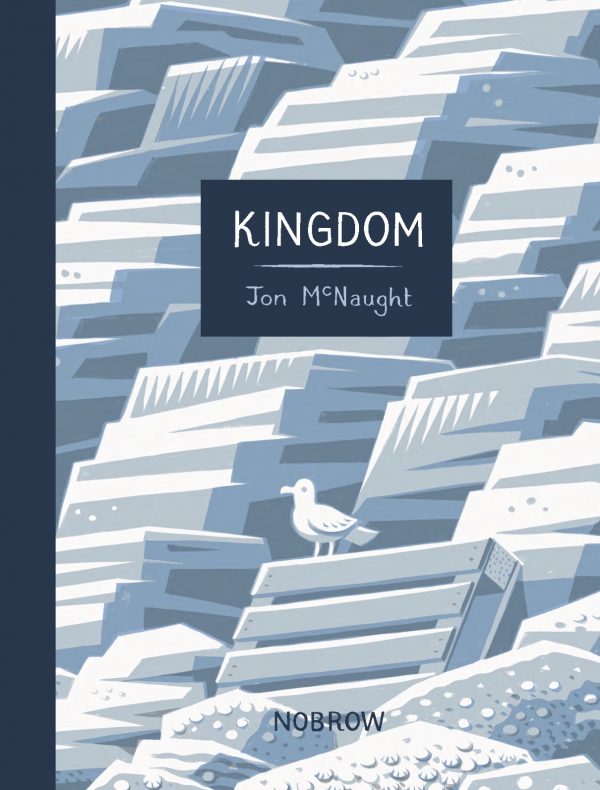

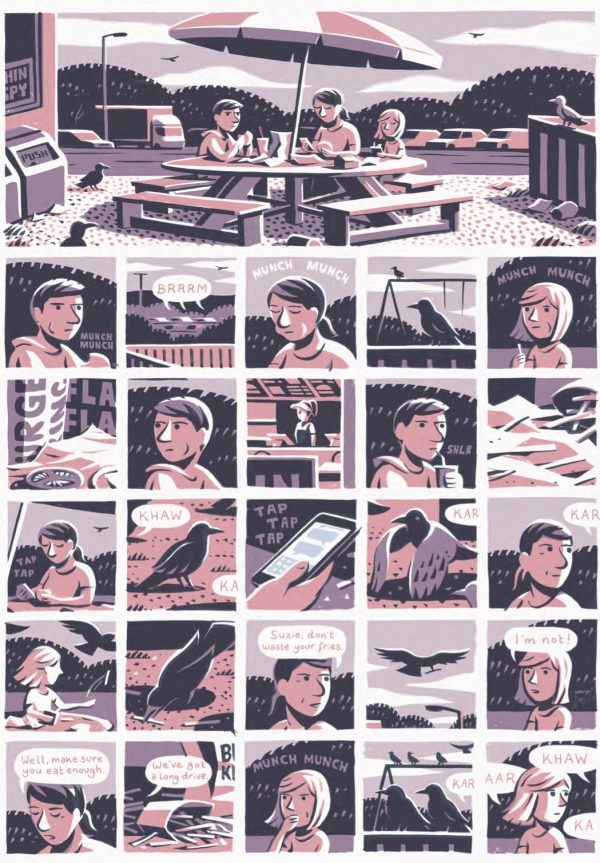

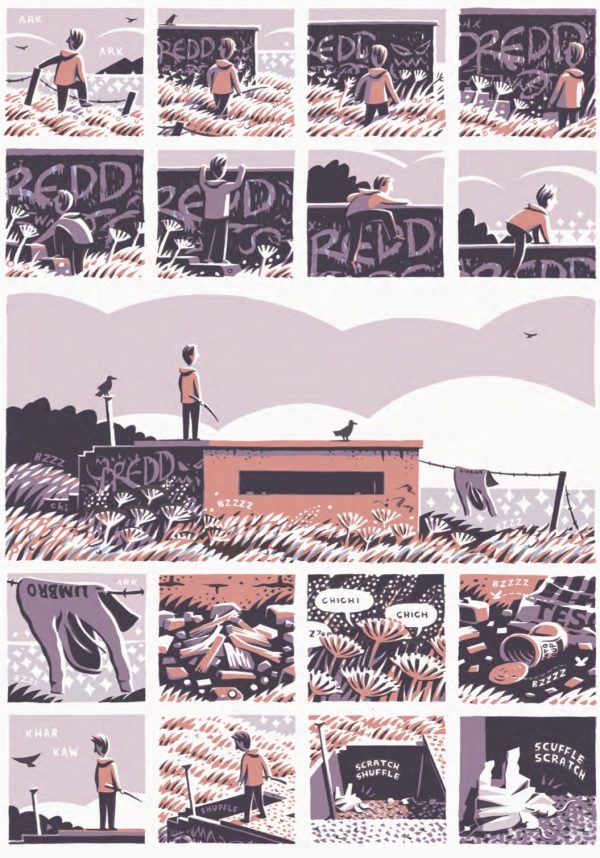

Jon McNaught‘s Kingdom follows a mother, a son, and a daughter as they go on vacation in England to a nature area. Their path there is littered with malls and fast food, and once there, it’s a struggle to get the son away from his computer games. But the grind of nature moves along whether humans choose to take part, mostly made apparent by the foreboding birds that inhabit the edges of panels throughout the book, making their mysterious noises, watching the family, and hunting for food, among other things. Nature operates as a tension that looms in the background of every activity family members take part in, just piercing the bucolic quality of their modern existence.

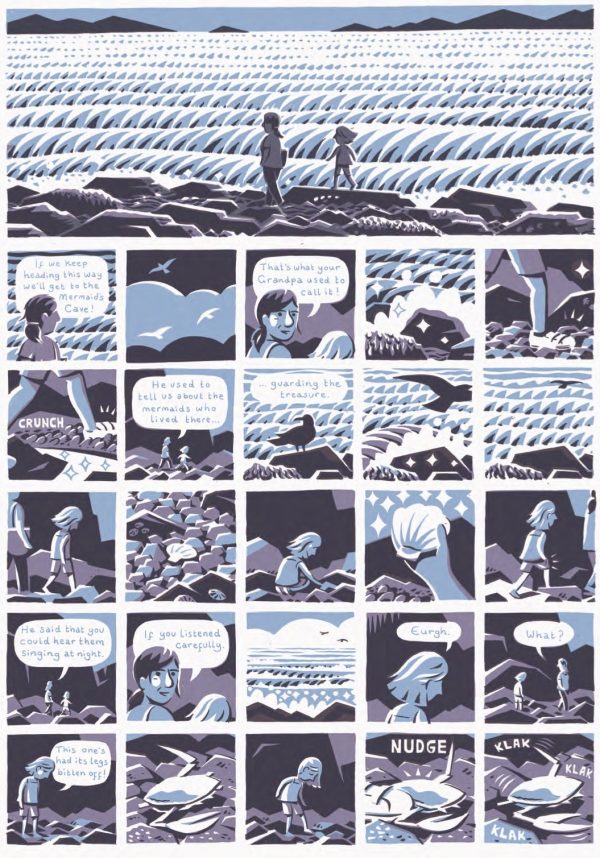

Once interaction with nature is sought, humanity proves inescapable. There are tattered remains of visitors past everywhere, from defense structures to discarded pizza cutters to hungover girls working a beachfront souvenir shack.

McNaught does a beautiful job at evoking this world he’s created, utilizing multiple small panels that create purposefully cluttered pages that manage to take the reader’s focus into the minutiae of the experience, points that the family might not have noticed, but rendering a full picture of the world they inhabit, from what they watch on television to what eludes them in a tidal pool.

As such, it’s not so much a criticism of the modern human world as a rectifying of the divide between it and the natural world. There’s an idea that pollution is part of nature because it is human-made and man is part of nature. Agree or disagree with the actual premise, it becomes a philosophical question about the nature of what belongs in the universe, of where humans stand. It is possible to tag one circumstance as good and one as bad, but when you move past the judgments and examine the situations, without passion, you find that the human experience and all its shallow technological clingings are as much a part of the world and an experience within the world as a bird hunting and killing a rodent.

Kingdom reminds me very much of the 1983 Virginia Astley album From Gardens Where We Feel Secure, which features Astley’s gentle piano work and some vocal chanting lilting over the sounds of the countryside. Some of the ambiances come from crickets, some from swinging gates. They work together to create a soundscape, not at odds. But what is at odds trying to fit in is Astley’s interaction, the human-made studio work, and it has to wind its way around the sounds of nature in order to eventually become part of the sonic experience. Eventually, human-made sounds in a studio and the sounds of the countryside become one, indistinguishable in any important way.

Somehow, it all works out and it all makes sense, and it all comes together in Kingdom, thanks to a glue that remains unspoken. The mother’s memory of vacation isn’t the same as what her children experience. The son opens up to the experience of nature, but through his own terms, not his mother’s. It’s all okay even though it’s all so different, and this is a beautiful rumination on the cross-section between tradition and moving on, about the escapable forces that peck away at the bubbles we build around ourselves, and about the hidden parts of the world that make it so rich.

Comments are closed.