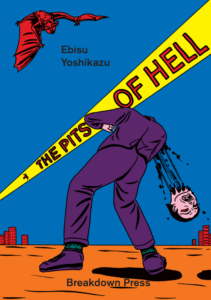

Story & Art: Ebisu Yoshikazu

Translation & Essay: Ryan Holmberg

Design & Typesetting: Joe Kessler

Publisher: Breakdown Press

Walking into a bookstore or comic shop in most of North America and wandering through the graphic novels generally means an onslaught of some of the hottest titles where manga is concerned — usually offerings from Shonen Jump like My Hero Academia or Naruto. Less common, but still prevalent, are stand-out works by well-respected creators like Taiyo Matsumoto or Jiro Taniguchi. It is rare, indeed, to find anything from the underground manga creators of the 60s and 70s — rare, but not impossible.

That’s where Breakdown Press comes in, with their array of brilliant oddities from Japan’s lesser-known comics past. The latest from them, Ebisu Yoshikazu’s The Pits of Hell, takes its readers on a wild ride through an angry, disturbed, frustrated man’s psyche, speaking to the exhausted working man through dreamlike glimpses of absurdity.

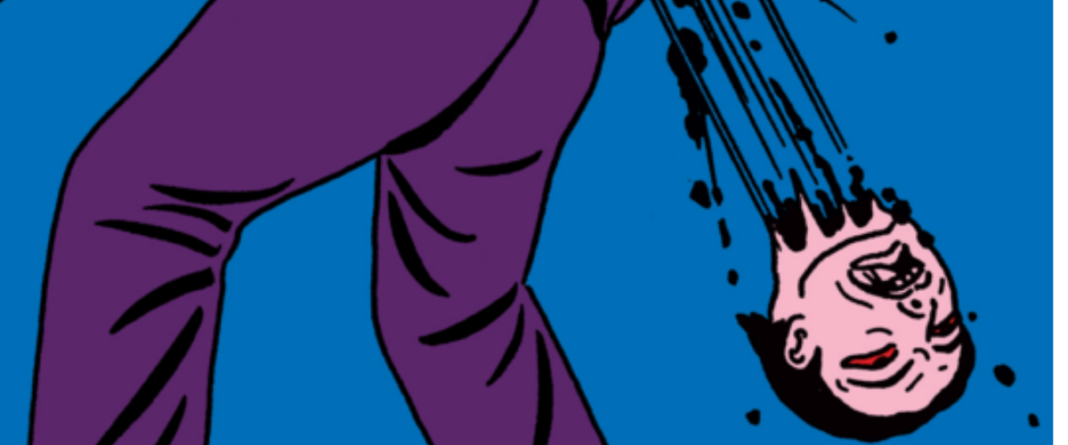

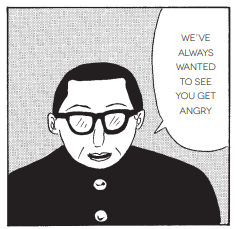

The fascinating, but admittedly uncomfortable, journey begins in a history classroom with “Teachers Damned to the Pits of Hell.” In it, a teacher who is rapidly losing his students’ attention is driven to the brink when he is told that his lecture is boring and then has food thrown directly at his face. He beats the offending student so thoroughly that he decapitates him, resulting in a round of applause from the rest of the class. One student simply tells him: “We’ve always wanted to see you get angry.” The teacher is left standing, sweaty and confused, with his late student’s bloody head resting on the floor behind him.

Several of the anthology’s stories deal with gambling, a vice shared by Ebisu himself. The supertitle to “Fuck Off” describes the narrative thusly: “1975: A brave and beautiful family in recessionary and sickly Japan.” In truth, it is the story of a man who plays pachinko all day, brings home winnings to his family, and is lauded as a hardworking, focused provider — all while being spied upon by their teenage neighbor attempting to achieve sexual gratification. “ESP” displays the drawbacks of collective use of psychic abilities to win bets on boat races through the perspective of a single distinct man in a sea of same-face salarymen.

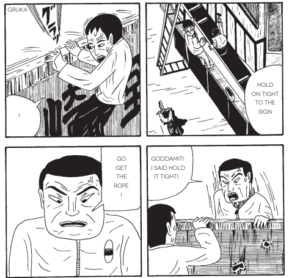

And then there is the frustration of the working man, for which Ebisu drew from his own experiences. In “Workplace,” a young man works in a sign-making company with only one other man, his nasty, overbearing boss. After being ordered around and belittled constant, the young man snaps and kills his boss in sight of everyone, smashing the man’s head with his sign-hanging hammer. In “Wiped Out Workers,” a put-upon CEO is distressed by the exhausted, lazy attitude of his Boomer-aged workers — a premise which is amusing in an era where Boomer CEOs are constantly talking about the inefficiencies of the Millennial generation. This hardworking CEO is driven by his frustration to kill his wife, and then beat and kill his workers as well.

There are more depictions of violence, distress, and misogyny within this collection, but they are all given a great deal of perspective with the volume’s backmatter, consisting of an afterword by Minami Shinbo, a rundown of the comics themselves by Ebisu, and an essay on Ebisu’s life and work by translator Ryan Holmberg. Ebisu’s constant apologies for the quality of his work are almost humorous, and allow the reader to separate the art from the artist a bit. This effect is further enforced by Holmberg’s essay, which describes Ebisu as a generally likeable and well-liked man who actually had a career in Japanese television for some time. His one vice, as mentioned above, was gambling, for which he was arrested in 1998. The description of him as a hardworking, sex-awkward, friendly uncle type hardly matches the extreme visions depicted in this collection.

But then the reader is asked to consider them as nightmares, as reflections of the most deep-seated, perverse desires and fears living in the mind of a worn-down generation. In this context, while the imagery does not become more palatable, it becomes embarrassingly relatable — for whom among us has not had shameful dreams of vengeance, or frightening dreams wherein we are dragged to hell (as in the last story in the collection, “Salaryman in Hell”)?

Ebisu’s artwork is not the polished, pleasing work many come to associate with best selling manga series, but nor is it without merit. As someone who drew much inspiration from graphic design, Ebisu’s panels are well-composed and intentional. His figures, though stiff and (probably purposefully) unattractive, are able to convey their rage, fear, and disquiet through over-the-top expressions that would seem cartoonish in any other context. He is considered part of the “heta-uma” movement, a phrase which can be interpreted as meaning “so bad it’s good,” though both Ebisu and Holmberg have plenty to say about Ebisu’s artwork not being intentionally bad, but rather the best he was able to do at the time. Regardless, there is clearly a great deal of effort and consideration in his work.

To say that The Pits of Hell is an acquired taste would be accurate, but also perhaps unfair to the work. It is far from being a happy, easy read, but with the context provided by its backmatter, it is an elucidating glimpse into the history of manga, and also the history of Japan to an extent. This single volume collection is available through Breakdown Press on November 5, 2019.