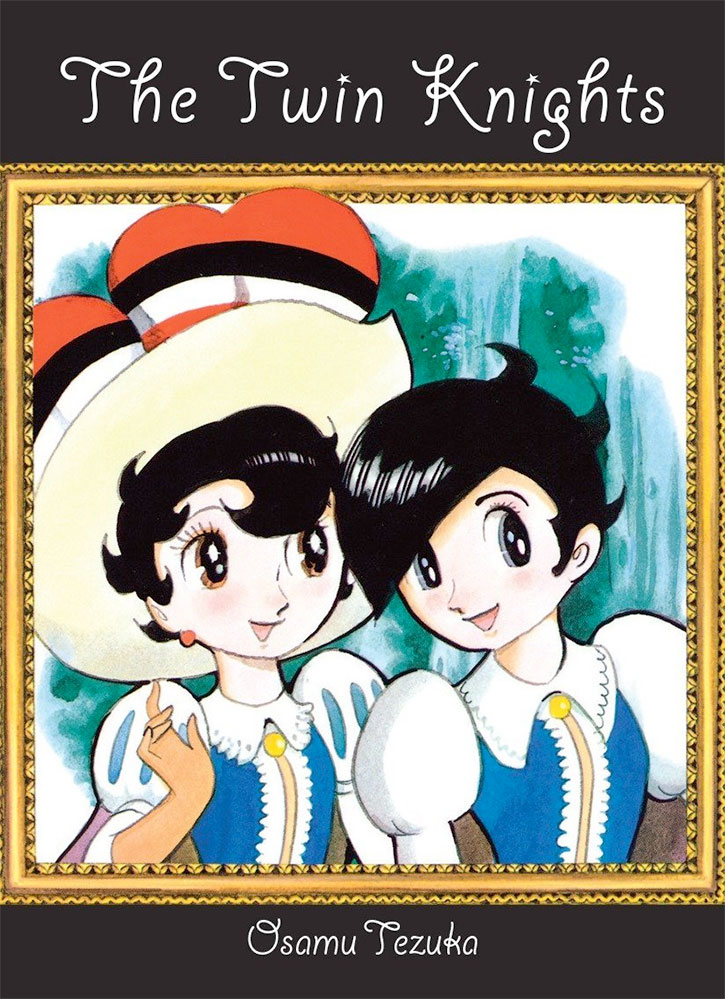

Osamu Tezuka wrote about everything from Buddha to fascism and gave the world its favorite little boy robot. He’s known for a hundred different things and involved in just as many others that most don’t know were his. Practically every manga he’s done is a venerated smash, to the point of a few series having some obscene paperback prices. He’s a legend, but one that didn’t really speak to me. Until I found one of his books that wasn’t about a shadow doctor or a demon hunter or any of the other boys’ stories that regularly accompany his name atop lists: my Tezuka first love was his shōjo work, girl comics, a prince and princess separated at birth. And it’s the end of the ’50s, so when we say girl comics.

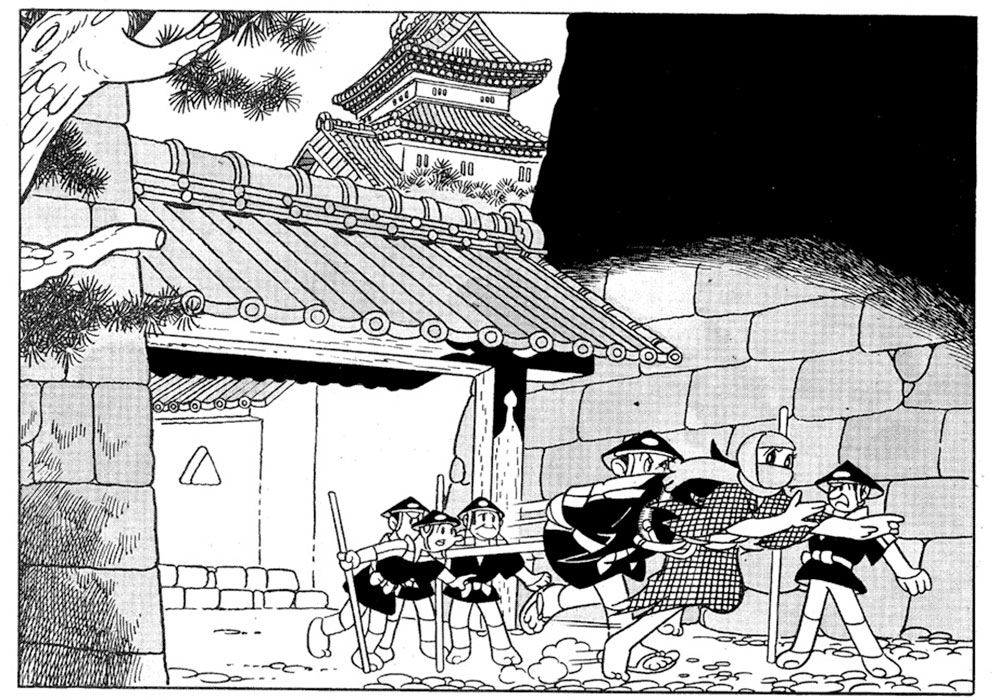

But what do girls want in a comic? Swashbuckling, magic, samurais, detectives, deceptions, angels, delinquents. Lots of jokes. Tezuka understands (and delivers).

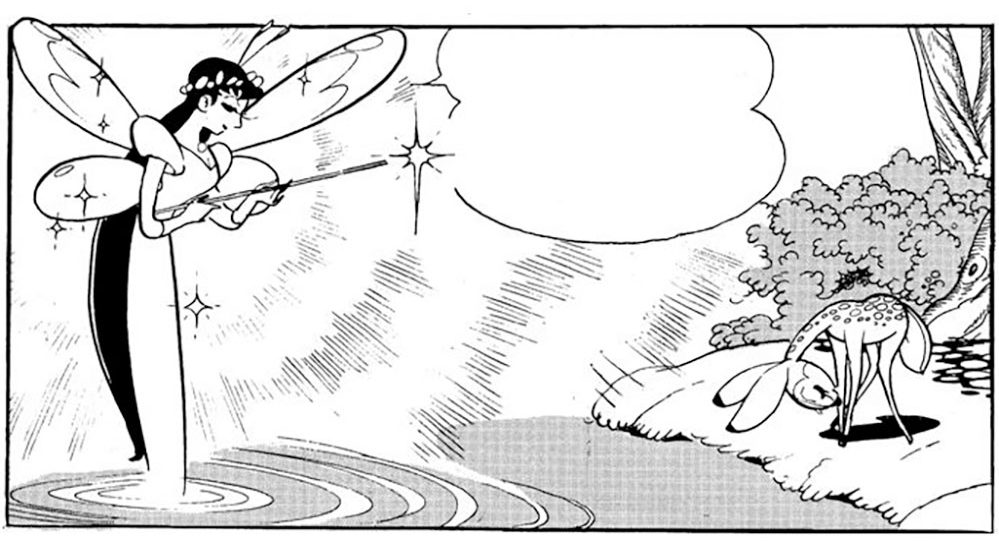

It’s fun, and even when things get choppy for the leads you know there’s a happy ending coming eventually. They’re fairy tale-ish kind of stories (mostly), with genre conventions to match. With switched faces at birth, a trickster sprite turns sweet, actually, and the mask to hide the princess’ face leads to intrigue. Courtly deception, one heir is stolen away and another has to live a double life in their place, until circumstance and swordplay bring them back together. A story starts out in a castle but moves naturally to the flophouse. Talking animals and angry spirits, monsters in the forest that gobble up children, and gangs of bandits who save them (by hiding them in a giant loaf of bread).

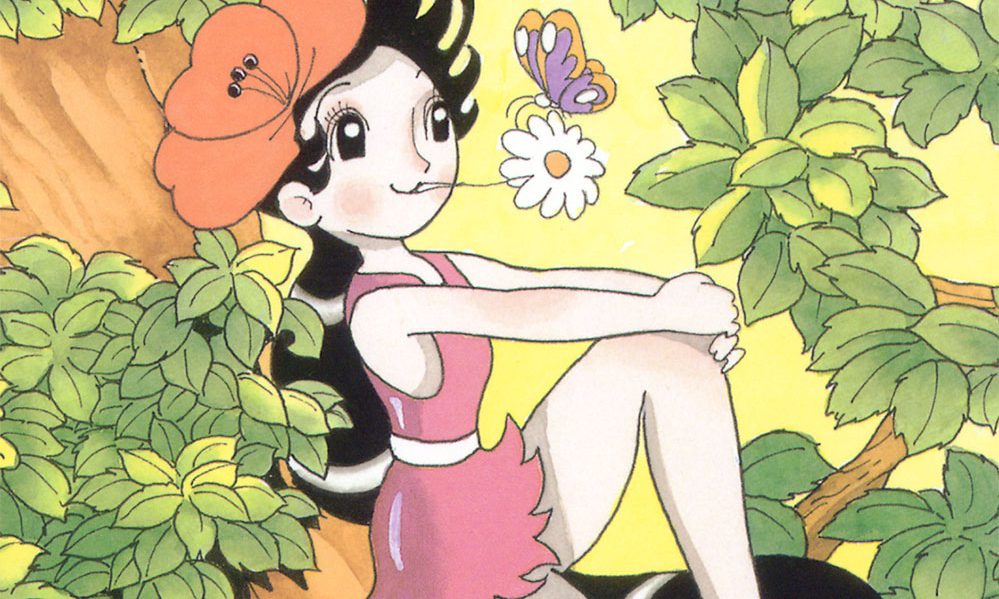

Folklore aficionados and other classroom regulars will be familiar with the focus on story over history. Iconic characters you meet and run with. The story of Little Red Riding Hood doesn’t normally spend time recalling the conditions under which grandmother fell ill or the days before the woodsman was old enough to swing an axe. You get busy with what they are up to. Tezuka’s Kokeshi Detective Agency. Pako, third grade, is incredibly observant, inquisitive, and fearless. She solves crimes. That’s it, off you go.

I guess that’s what qualified them as girls’ comics. The detective, the fairy, princess, kenshi, outlaw queen, crossdressing swashbuckler, the heroes of the stories are all heroines. The gender binary sucks, it was used to hurt people then, when the industry was drawing dividing lines in print, and it is used to hurt people now. The idea that what makes these comics for girls is they are about girls is insipid. Tezuka’s dated but teachable shōjo comics are a blast because he subverted the norms, the girls who wouldn’t stay home when told to are raised up to the station of hero. They feel every bit the shōnen story, maybe even a little more sophisticated? The action that was supposed to be purely boys’ books’ territory is just as present, but there’s a bunch of examining gender roles and class expectations where the nosebleeds or BM jokes would be. She’s got powers beyond those of ordinary people, and she uses them to be kind.

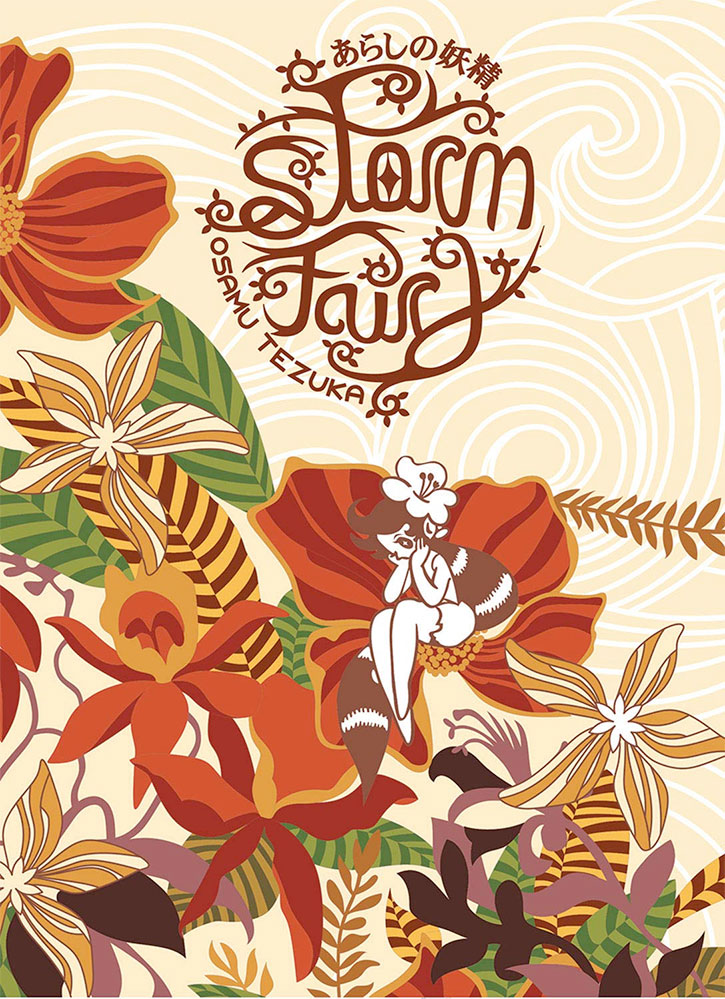

The big sell for these books’ look is they are also very ’50s and feel it. I was drawn to Tezuka’s work by his iconic, vintage simplicity, right there with Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks in creating the aesthetic that would define the time. I saw Snow White (with a dash of Little Nemo) in the creatures of the forest in Twin Knights. The Edo period in The Storm Fairy sure reads like A Touch of Zen but fashioned by the king of ducks Carl Barks. These books really are extra-pleasing on the eye if you enjoy the old time good stuff.

Tezuka’s art is deceptively simple at first glance. Cherubic, stocky figures, so retro! The broad operatic gestures are streamlined like a pinstriper. Super Uderzo also. Then see the patterns on the clothes, the delicacy and detail. The castles, cities, scenarios that surround the girls follow through immediately behind, and then you’re a little surprised you could’ve ever felt panels so busting with work were unembellished. Tezuka fills the page as water fills the pitcher. There’s a Geof Darrow, Evan Dorkin panel and page density thing happening, just as subtly. Not simple at all, Tezuka is someone who knows how to do everything enough.