I write a lot about contemporary art, and one of the areas that I find so many people get hung-up about is meaning. That is, the specific meaning of a specific piece of art, and also, the general idea that a piece of art must have a meaning. People find it hard to fathom that an object or an experience might have no meaning, or no implied meaning, or no meaning coming from the artist that should matter to the viewer. Meaning, in so many instances, is what the viewer brings to the work, though bringing meaning is not always mandatory.

The ability to accept a piece of art as the thing it is and not the thing it stands for is an ability directly transferable to relationships with other people. It’s not necessary to decide someone is this kind of person or that kind of person. The traits that would normally lead someone to make those characterizations are just the person. This might be even harder to grasp in the 21st Century, where labels have overtaken our own views of ourselves. There seem to be hundreds of labels for numerous things, whether it’s the type of heavy metal you create or the gender you identify with. And psychological labels have started to function as name tags that define who a person is to the person that is about to encounter them.

None of this is good or bad. All of it just is.

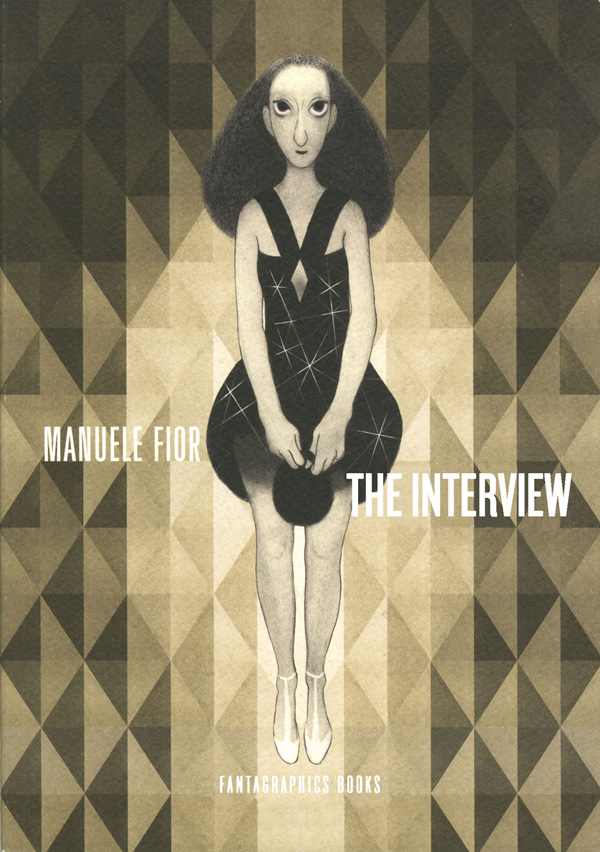

These are the thoughts I had when reading Italian creator Manuele Fior’s The Interview, a mysterious, elegant book that wraps these ideas around a mysterious event on the Earth and one man’s relationships with several people as the event unfolds.

Psychologist Raniero faces several traumas in succession, including a car accident, a pending separation with his wife, and victimization in a crime. He also encounters illusory diamond-like lights in the sky that instill a giddy feeling when he sees them. Obviously the rest of his life is not so elegant, his reaction to it not so unfettered, and he approaches everything and everyone as if he needs to deflect them for his own safety, and the exhaustion of having to do so saps any energy to care.

It’s an encounter with Dora that slowly begins to transform his experience. She has been committed by her parents, who are in opposition to involvement in a social movement among young people endorses “emotional and sexual non-exclusivity” as the societal standard. The interaction between Raniero and Dora focuses somewhat on this, but also on the bigger picture involving isolated incidents of colorful figures in the sky, which brings Dora to claim she is in contact with extraterrestrials.

With an emotional link to Dora becoming more and more solid, even as Raniero’s connections with others slowly disintegrate, Fior depicts a world grappling with events that seem to demand interpretation, at least by the typical human experience, but are probably better, like the art I spoke of before, accepted and absorbed on their own terms. As the end seems near and reality moves more and more into a dreamlike state, it’s up to Raniero to decide for himself whether any of this is to have any meaning, or whether he needs to cling to what he already knows, rejecting any evolution being offered to humanity.

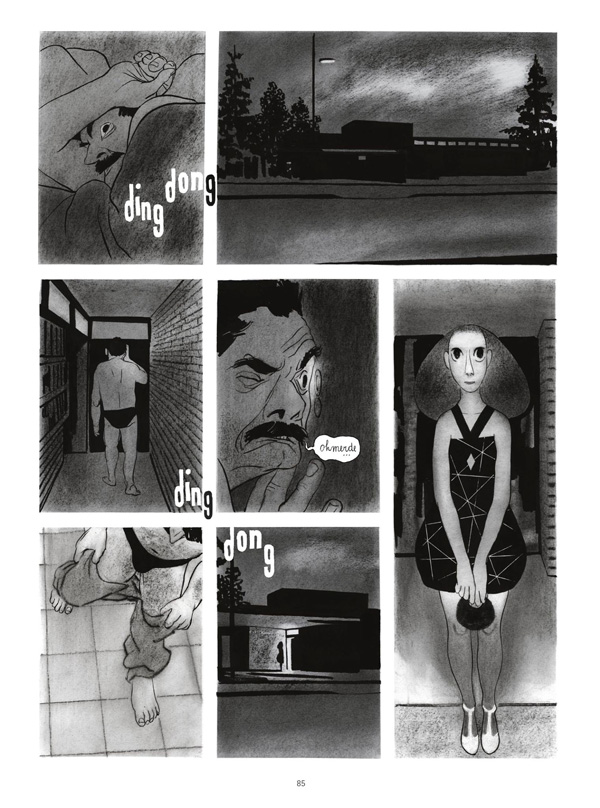

Fior’s story unfolds in a beautiful, dreamy black and white that envelopes the reader into the same state the characters themselves inhabit. The mystery, in the end, turns out to be not the lights in the sky, but other human beings, and solution, it seems, is one that takes some of that mystery out of life, but perhaps creates all new ones. The human condition becomes a constant quest for meaning, and each time that quest is solved, another one inevitably takes its place, because meaning is not a tangible item you can hold in your hand.