Through the years, one thing that has consistently figured into the teenage remembrances of people I’ve known is music. We might have had completely different lives in completely different places, but everyone exhibits musical memories of that age that often form some sort of thread by which we trace our biography.

One of the strangest experiences in life along this concept is when you meet someone in your 40s, you hit it off, and then you share your musical biographies and find out you were incompatible in your teens, that you would have actively frowned upon each other because of musical taste. Such times make it clear to me not only how powerful music is in the young, how defining it is, but also how limiting it can be.

And then there’s the exact opposite situation, where someone you bonded with so deeply over music can, years later, be far removed from the person you are.

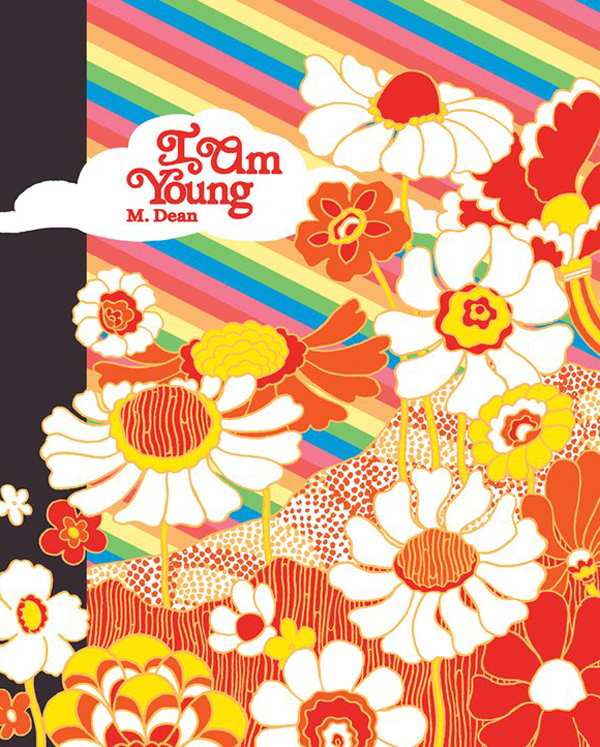

These are the circumstances that M. Dean’s I Am Young speak to. It’s not a depiction of the importance of music in young folks, but an examination of its place in young identity and relationships. Often in your teen years, you become an amalgamation of your passions, a walking signpost for the things you like, and among those affectations set the influence of music. Sometimes it becomes so powerful in a person that it blossoms into a subculture, while other times it marks your key to be welcomed into the mainstream of whatever society you enter. On occasion, the signpost works as a signal to one other person and that is very much what Dean addresses in her stories here.

At the center of the narratives is the story of George and Miriam, who meet for the first time after a Beatles concert and grow into something more. Dean checks in with them over decades, with the biographies of the Beatles acting as touch points in their own stories.

But this is not a love letter to the Beatles or any one kind of music, and Dean fills the rest of the book with singular slices from people’s lives during moments of decision where they try to figure out who they are, what they are doing, what’s ahead, and where they might have gotten it all wrong.

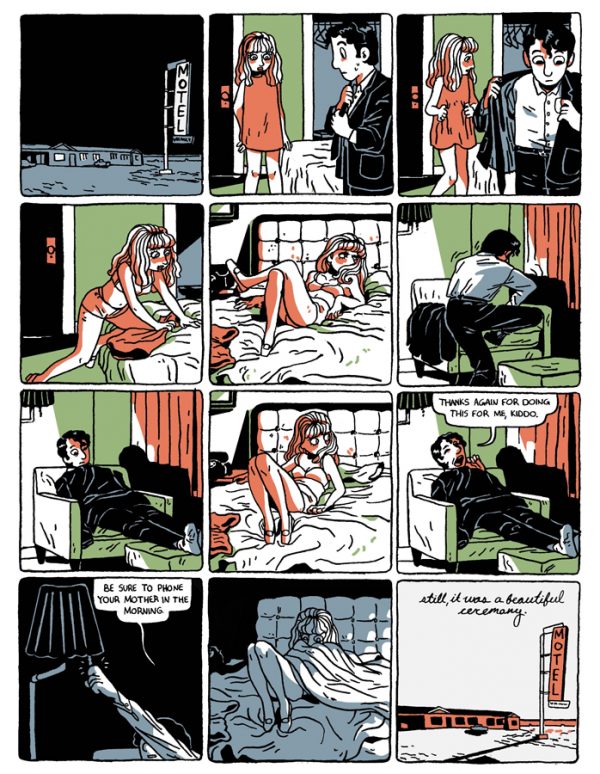

These moments are sometimes major, sometimes slight, but always important. “Baby Fat” tells the story of Pepe and Roberta’s speedy marriage in Vegas, forever linked in her mind to the sound of Eddy Arnold on the radio. They didn’t marry out of love, but for Pepe to get a marriage deferment to the draft, and the deteriorating situation pounds down on Roberta through the years.

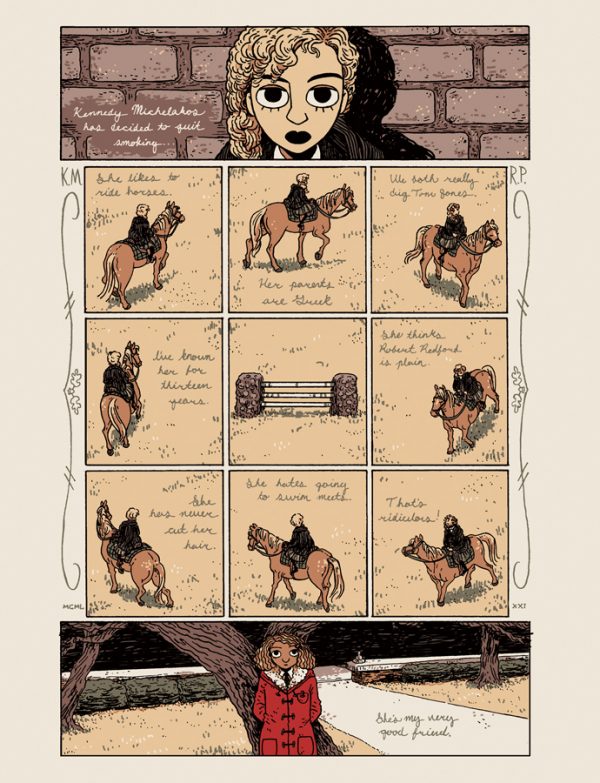

“K.M. & R.P. & MCMLXXS (1971)” visits the friendship between Kennedy and Rhea, and their plan to write novels. They bond over a love of Tom Jones, but that may not be enough, as Rhea soon finds herself drowning in Kennedy. Every idea Kennedy has, every affectation, every word she speaks, it all washes over Rhea like a tidal wave that incapacitates her attempts to express herself over the noise of Kennedy. A lot of friendships find themselves struggling with this dynamic, especially involving the idea that one person has all the answers, and Dean’s conclusion speaks to what most people eventually realize.

Other stories capture little moments. “Strange Magic” follows Lisa on prom night, tripping on acid as Electric Light Orchestra plays, though she dreams of the Beach Boys as she reaches inside herself, far from the crowd at the dance.

“Nana” finds the title character reacting with hostility at the idea that the popular girl, Amanda Jordan, also loves Karen Carpenter, but for, as Nana qualifies it, all the wrong reasons.

In one of my favorites stories in the book, “Alvin” introduces a Chuck Berry-obsessed kid given to speeches on the cultural importance of Berry and implications of rock music in the ‘50s in context of marginalized African American culture. Alvin’s smart and his taste is eclectic for the ‘80s, but his penchant for lecturing other kids probably causes him more social grief than his taste. And in butting up against white nostalgia and wanting to tear it down, he really is just open to not actually being lonely. It’s a lovely, small story with large, subtle implications.

Dean’s art runs the gamut of styles, particular to the story she’s presenting. The George and Miriam stories feature a clean black and white style with well-rendered settings and big-eyed characters. “Strange Magic” features trippy color with swirls of psychedelia and disco lights, impeded on by creeping dark blues. “Alvin” sets a tone by allowing browns to dominate over tans with simpler line renderings. The story of Kennedy and Rhea takes on a scratchy intricacy with more traditional but faded colors, a style that resembles children’s books like Eloise, which is perfect considering the story.

And so while the focus of Dean’s book might appear to be music, it’s really just identity, who you are and who we are together. Music becomes something we cling to in an attempt to find clarity and definition to ourselves and any situation, to bring order to the chaos of both the moment and the extended drama of life, but as an art style, music is the presentation of these more personal circumstances. Music is the announcement of who we are, but Dean is just as committed to depicting what lies under the songs.

This looks amazing! I really want to read this! The art style s simply beautiful, and I love coming of age stories.

Comments are closed.