Millennials are often portrayed by the older generation – my own, to be clear – as a generation of victims. Like most cross-generational proclamations, this is a self-righteous pile of bull built from Gen Xers’ and Boomers’ stumbling reading of Millennial discourse, as well as some resentment for our own repression and the ability of Millennials to refuse to pretend everything is just okay. All of us Gen Xers (and Boomers, I don’t really know which I am) wish we could have acted that way, but we didn’t.

And yet, like so many cross-generational proclamations, there is a grain of truth, no matter how big the eventual misinterpretation of it becomes.

Michael DeForge’s protagonist in Big Kids is living his victimization and accepting it as reality. Bullied by friends and enemies alike, even by his own lover, alienated from his parents and relatives, the only decision Adam really seems capable of making is to not engage in school. As it is for so many victims, a further self-destructive choice is the one thing readily available to claim as his own in a desperate bid for some kind of self-determination.

If Adam sees himself as a victim, everyone around him only affirms that self-image. But that’s about to change, of course.

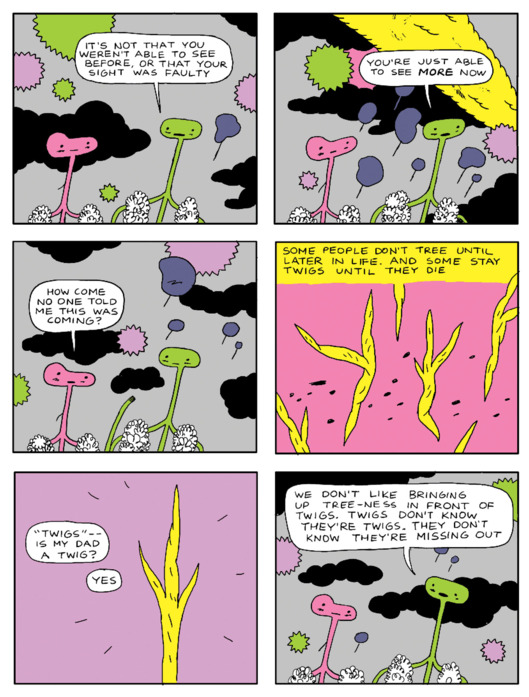

Adam appears to have psychotic break from reality, one in which his actual vision of what the universe looks like is replaced by DeForge’s further stylistic abstractions. Family life takes on the dynamics of another, harder to comprehend dimension that makes existence in general something more than typically expected, even down to the most mundane detail.

But Adam realizes this is not a psychotic moment at all, but an awakening he shares with others.

This transformation can be taken several ways, the most obvious one being a symbol of maturity that offers perspective, but I think it’s more complicated than that and I don’t believe DeForge is a single-dimension thinker. As Adam traverses his new perspective, he learns the trade-offs of heightened awareness, the pitfalls of having perspective, the dark side of having control. If his previous existence was painful and out of control, his new one is not without complications that make him feel even harder than he did before

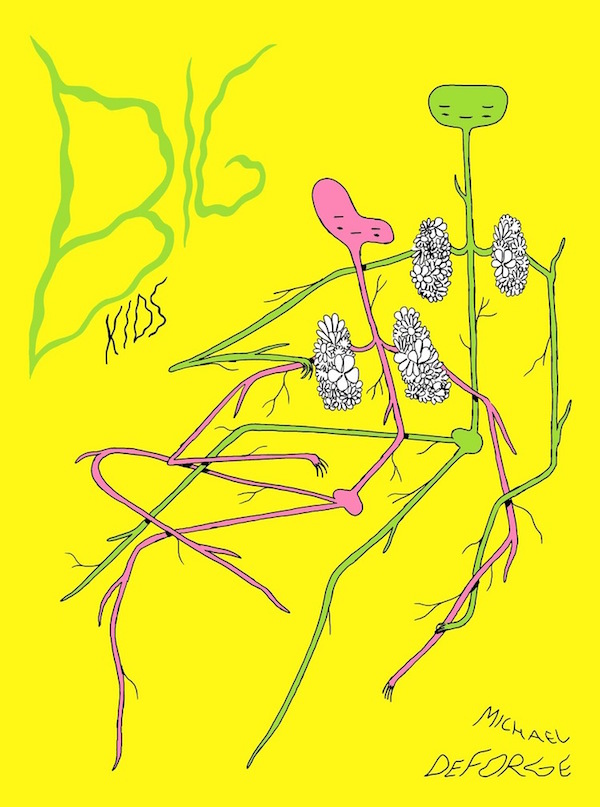

As is typical of DeForge’s cartooning, you’re not likely to confuse it with anyone else’s. His choice of offbeat colors, his round heads, his fleshed-out stick figure bodies, his geometric backgrounds, these are all so distinct, and well-utilized regardless of what story he chooses to tell. These always shape his universe as distant and stylized in such a way that you’re continually surprised by the genuine emotion they elicit. They’re put to particularly strong effect here, with the gradations of his abstraction functioning as different levels of psychological growth, literally helping to structure the narrative in a challenging and vibrant way.

As a fable of personal and generational growth — and an examination of the challenges of trying to measure yours against others — DeForge’s tale unfolds on its own terms, with its own symbols employed. Never has a cartoonist’s work been quite so alien, yet so very familiar at the same time.

Comments are closed.