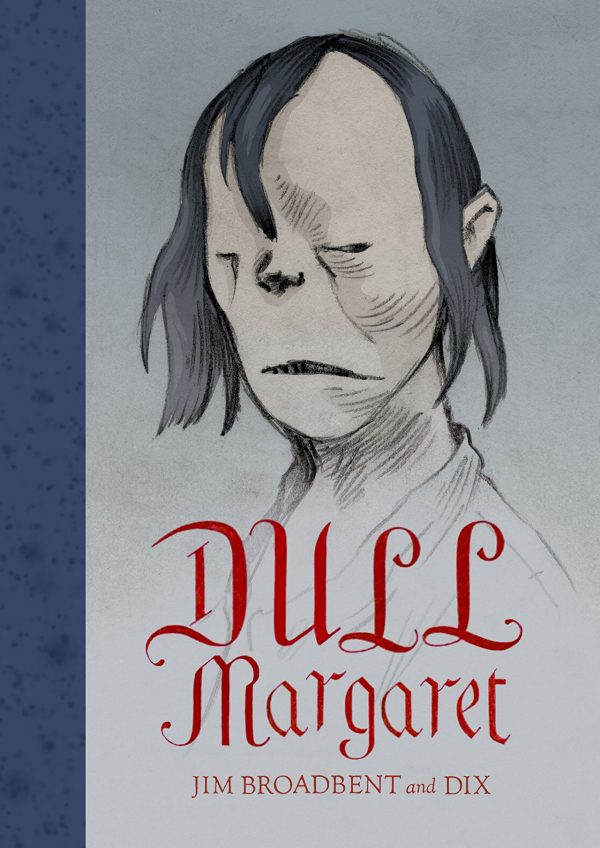

Less a linear story than an intense incantation filtered through a fever dream, Dull Margaret is the work of British actor Jim Broadbent, his debut graphic novel in collaboration with artist Dix, who is best known for his cartoons in the British newspaper The Guardian.

In the press materials, Broadbent talks about his influence for the book. Part of it was born from encounters with the coastal marshes of Lincolnshire, which is known for its long coast and salt marshes, with salt production dating back to prehistory. It’s this prehistory that Dull Margaret partly comes from, but as Broadbent points out, she also steps out some of his favorite paintings, most directly a 16th-century painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Broadbent names other artists whose have guided his vision of the graphic novel — Goya and Rembrandt for instance — but the one at the center, Bruegel’s ‘Dulle Griet’ (Mad Meg) is an unmistakable relative. In style it could be compare to works by Hieronymus Bosch with its sweeping, cluttered grotesqueries, but at center is the figure of Mad Meg, an apparent type in Flemish stories at the time that Broadbent is borrowing for his own work.

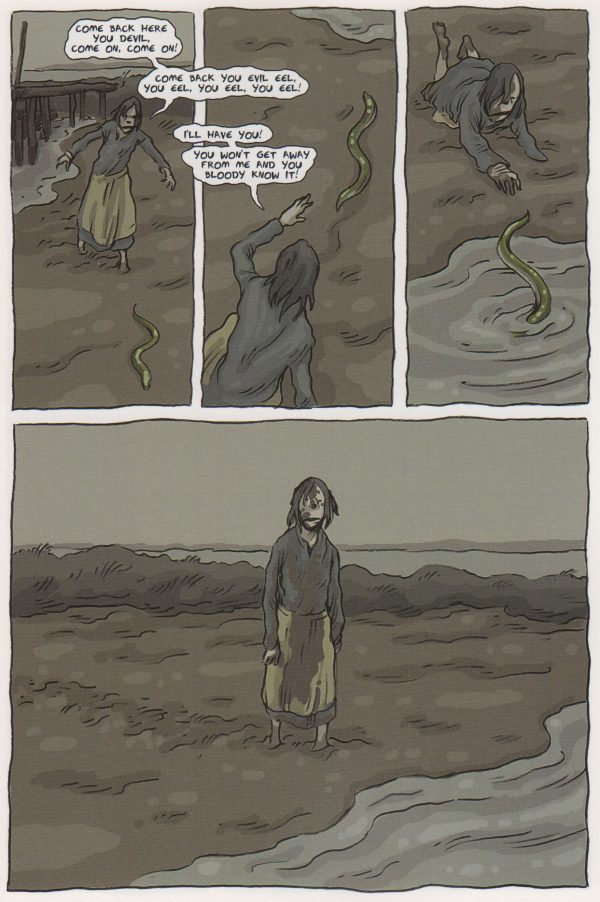

Mad Meg was characterized as an aggressive woman, and perhaps Dull Margaret has a bit of that in her, but it’s tempered by sadness, confusion, and desperation. We first meet her as she ascends from the water, fully formed and into an existence that though she appears to us new to it, she is definitely already a part of. Margaret speaks in repetitive nature to the point where her words can feel like chants — “Come back here you devil, come on come on! Come back you evil eel, you eel, you eel, you eel!” — interjected with more coherent sentences that gives the impression that she is talking to someone she can perceive but we cannot.

Margaret is a decrepit human figure with a misshapen head that only appears partially-formed, though few of the humans featured in the book look as if they are doing very well. It’s a bleak world these creatures live in, but Margaret goes about her business in a fable-like progression that sees an injustice done to her and her quest for vengeance.

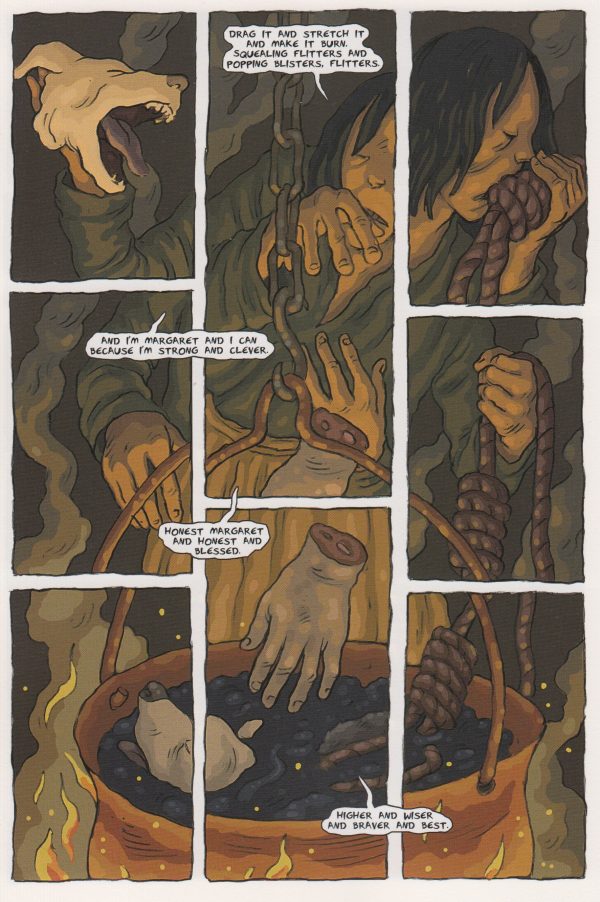

But it’s also a quest for happiness, which Margaret spells out at one point, directing the powers beyond her to grant her gold or a friend, and putting her own constrictive terms onto the deal as she takes part of a hanged man for a witch-like ceremony that leads her to her request, but also on her cryptic odyssey where she encounters three mysterious beings on a ship who help deliver the subject of her vengeance.

Broadbent’s story is elusive. You know what is going on, but the presentation of it is alien and frightening, and that’s entirely due to the masterful artwork by Dix. Though it might be a temptation for some to evoke the artistic influences for the story in a direct way, Dix renders this a story guided by its own visual tone, its own illustrative world.

Dix’s imagery is dark enough to match the emotions guiding the narrative — and I don’t mean dark tones, I mean dark panels, some of them so dark you have to squint as you would as if in an actual room in order to make out the features. Other times its just a pall of gray, like a weight on the creatures that inhabit this earth, or depressing browns to depict the mud and shit and souls there.

It’s perhaps best to approach Dull Margaret not as a straightforward narrative graphic novel, but as a sequential painting or visual poem. There is sense to be made of it, but that’s not its best quality. Colors, figures, chants, and screeds all come together to create something more than its parts, a work that suggests that we all might be a little like Margaret, trudging though a harsh reality, wishing most of all for love and safety.

I’m struck by why selecting that Mad Meg figure from history/myth and into the now. The provenance of the creators is first class. Looks really good.

Comments are closed.