Two new books from Retrofit/Big Planet use the comics form to meditate on the psychological overtaking the physical, both with strong executions in different styles.

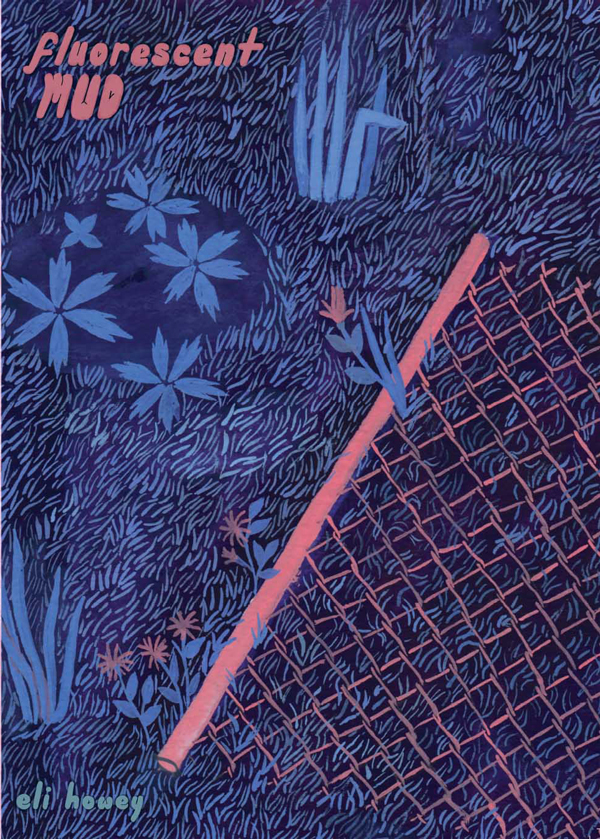

Reading Eli Howey’s Fluorescent Mud is like wandering through someone else’s mind without a guidebook. I think Howey might agree. The description of the book on Howey’s website says the same thing, just maybe better than I’m putting it: “Using a visual language of symbols and codes, the book follows the main character through a series of seemingly unrelated and unexplainable experiences. These occurrences are almost surreal, depicting the various states of mind, memories/thoughts/feelings and sensory experiences affecting a subjective retelling of events.”

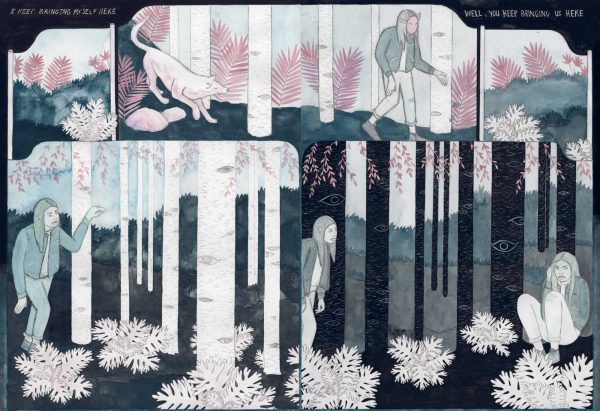

Disconnection is at the center of the book’s theme, and disconnection is what plagues the main character, who wanders through life with the most mysterious of purposes. Displaced from emotional connections for the most part, without any discernible — or, at least, presented within the narrative — goals in life, Howey’s main character is someone to whom life happens and the only defense she has against that is let go of her connection, and therefore not feel.

What follows is a series of events that Howey admits appear unrelated, though that random quality probably has more to do with the character’s perception of how things unfold than the way reality falls into place. Whether she’s struggling with her friendships or meeting strangers in strange towns, it always seems like she’s wandering through the moment, and at times, her perceptions descend into incoherencies. At one point, this withdrawal is drug-induced, but each subsequent time she checks out from the moment appears to not have any catalyst from outside her own body.

Howey unleashes this world through hand-painted gouache and watercolor panels that offer an appropriate dreamlike quality to the book, cementing the character’s experiences well outside any shared reality. Landscapes become unhinged, and colors become as luminous and unpredictable as the path of the mind, paired with words that relate incomplete contexts and justifications.

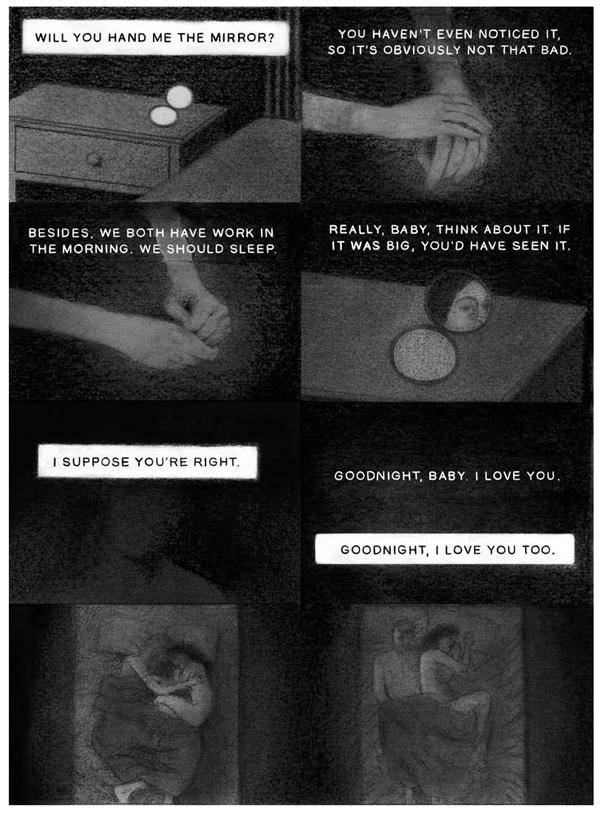

Laura Lannes‘ short John, Dear covers similar surrealist territory, but in the form of a body horror tale that has the unreality slowly overtaking the linear narrative. In it, a woman meets a man named John and initially hands her autonomy over to him at the beginning of the relationship. This sets the tone and John views the self-immolation of her emotions and ego as the norm for how the relationship should continue and progress. As authority is handed over to him, she shrinks into a more submissive personality that exists only in reaction to John’s existence.

The horror begins when John mentions a facial flaw to her while in bed. Obsessing about it, the woman discovers that black holes have appeared on her skin. As her anxiety and depression build, so do the holes, eventually cropping up all over her body, elevating her distress as well as her tension with John, whose relationship demands begin to tax her alongside the mysterious disease.

As a tale of psychological horror, Lannes’ work is particularly effective, but it takes on a larger meaning in the context of the relationship as she portrays it. The casual misogyny of John as he takes advantage of his partner’s trust and inserts little emotional bombs that overtake her plays out like a cautionary fable of gender relations. John’s psychopathic tendencies become physical in her form and then reverse back to cloud her mind and doubt the very essence of herself.

This is pushed further into darkness by Lannes’ art, black and white with collage elements and illustration work that is engulfed in the darkness of the bedroom, alternating with the stark, almost painful revelations of the disease on her skin. It’s an amazing visualization of an abusive relationship, vividly capturing an emotional state in a way that those who have not experienced it can absorb and hopefully hold with them for both empathy’s sake, and the ability to recognize in themselves.