Written by Gabriel Serrano Denis

The hydrogen bomb became a literal walking creature of death in 1954’s kaiju classic Godzilla. Throughout its 70 year rampage, Godzilla has stood in for several similar means of destruction, even switching sides at times to balance out the chaos against other symbolic creatures. In 2023, Godzilla comes back as a stand-in for war, along with its emotionally scarring ripples that left so many soldiers with no direction home. Godzilla Minus One’s monster continues a tradition of humans fighting against adversity and coming to terms with the horrors of a new world order. This time though, as with the best renditions of the monster’s destruction, the kaiju action is as tension-filled and engaging as the human drama.

One interesting thing to note in Godzilla Minus One is that the film immediately starts with the main character and his ordeal during the tail end of World War II. A kamikaze pilot who couldn’t fulfill his honorable death, we’re immediately thrown into the human turmoil at the center of this story. Shikishima, played by Ryunosuke Kamiki, is a pilot struggling with the guilt of surviving the war, and unlike the documentary-like approach of the original Godzilla film in which we are introduced to the characters and the monster slowly, a young Godzilla is quickly introduced and makes landfall on the island in which Shikishima made his emergency landing, which adds another layer of guilt and PTSD to the battered soldier right at the beginning. Arriving in Tokyo after witnessing the horrors of war as well as a whole team of mechanics slaughtered by a prehistoric beast, Shikishima is forced to live and find the means to rebuild his home despite the angry looks of those who know of his self-proclaimed cowardice. It is in this moment of conflict that Shinishima meets Noriko (Minami Hamabe), a woman with a baby she rescued in tow who attaches herself to Shikishima in a bid for survival. Soon the three survivors become a sort of family, with only Shikishima not wanting any part of it aside from helping them stay afloat. It isn’t until he gets a job helping the government gather and destroy sea mines that his eventual re-encounter with Godzilla will take place.

Director Takashi Yamazaki follows up on Hideaki Anno’s Shin Godzilla (2016), itself a beloved and successful take on the iconic monster, with a story that melds human drama with kaiju action. Unlike Anno’s film, bureaucratic and political dealings are mostly just mentioned and kept to the sidelines, such as mentions that the US and Japanese military cannot intervene for fear of escalation with the Soviet Union. These details are important to the story and are rooted in historical context, but Yamazaki’s main interest is in his characters and the how and why they must destroy Godzilla. The focus thus is on Shikishima’s desire to find retribution through the destruction of the creature and an alliance between veterans who recently went through hell only to be thrust into a fresh pit. This makes Godzilla Minus One a unique entry that puts to shame all American attempts at bringing Godzilla and his victims to life. The historical context is unique as well – a Godzilla period piece had never been attempted and director Yamazaki delivers a lived-in and detailed post-war Japan that is both impressive and heart-wrenching to look at. The set design and careful placement of the camera immerses the viewer in the ravaged city, itself a mirror of Shikishima’s shattered soul. Yamazaki puts so much attention to the character’s surroundings and to Shikishima’s moments of intense PTSD-related outbursts that one could simply read Godzilla Minus One as a war movie akin to Jarhead (2005) and Platoon (1986). The drama between Shikishima and Noriko, as well as fellow comrades in his mine-hunting boat, grounds the film in ways few Godzilla films have been able to.

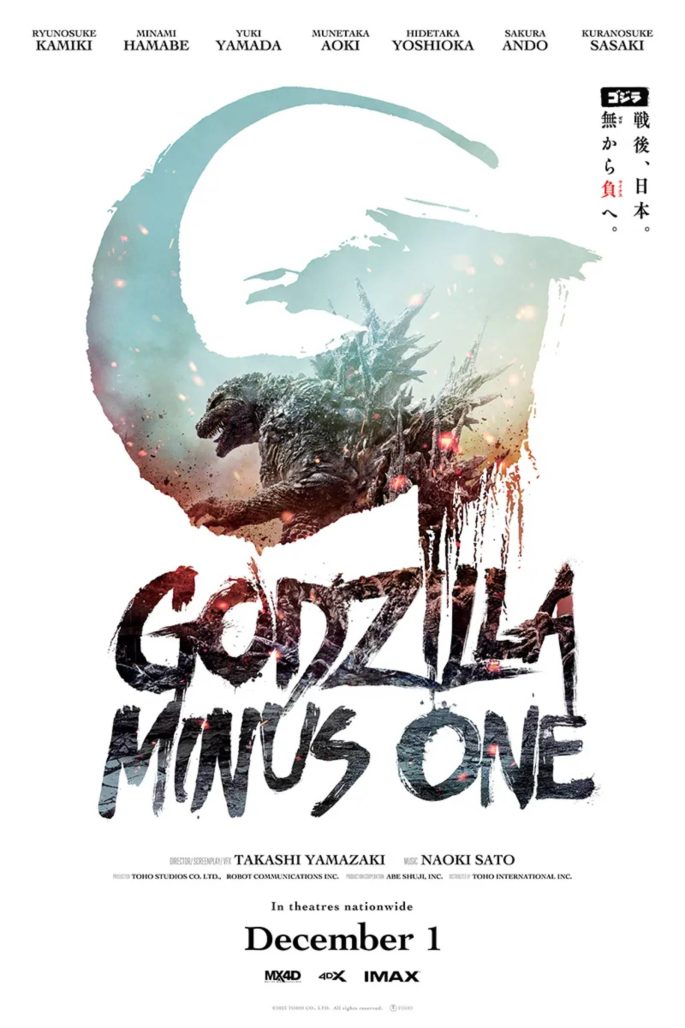

And of course, there’s the king of the monsters himself. Godzilla’s scenes are monumental and terrifying, Yamazaki never shying away from getting up close and personal. So confident is he in the monster’s design and visuals that this is perhaps the closest we’ve ever been to the king in the Japanese films. Anno’s creation might just edge out Yamazaki’s as the most evil and downright scary, but this Godzilla is by far the most menacing and impressive to look at. A cross between the original 1954 design and the Heisei era design, Godzilla looks powerful. Even in his younger form seen at the beginning of the film, we get to see him eat and throw people around like the T-Rex from Jurassic Park (1993). It’s terrifying, but also quite pleasing for fans who enjoy the carnage. There is even a Jaws (1975) reference in a particularly horrific chase in the ocean in which Shikishima and his crew throw mines into the ocean and shoot at them while Godzilla approaches, his head and spikes peeking out of the vast ocean. It’s one of the best sequences in the franchise’s history.

Yamazaki takes cues from the more recent American Godzilla films for the titanic moment in which the monster arrives in Ginza. Newly rebuilt and thriving, Godzilla wreaks havoc and Yamazaki places the camera straight on the ground. Anno also did this but his frantic style yielded other, more chaotic results. This time, we are there, amongst the ruins and awaiting the impending claws to bring down doom. We see the entire process of Godzilla prepping his heat ray and witness along with the thousands of citizens as the blast lays Ginza to dust. Because Yamazaki has carefully built up the relationship between Shikishima and Noriko, this moment is all the more powerful and horrific. We are not seeing hollow humans running from Godzilla, but rather hoping for these full-fleshed characters to escape the carnage alive. This is where Yamazaki shines as a director of action – not only does his environment feel real but his camera is purely centered on the people. There are rare aerial points of view in this and other scenes. If Ridley Scott made a Godzilla movie, it’d be somewhat close to this. But it is Yamazaki’s vision and talent – brewed in decades of experience in sci-fi and action films as a visual effects supervisor and then as director, and bringing inspiration from the best to display monsters and war on the big screen – that make Godzilla Minus One a truly memorable experience.

At 70 years old, Godzilla still manages to bring in new ideas and remain relevant. In the hands of Takashi Yamazaki, Godzilla is not necessarily an aspect of war and destruction but war itself. An external war, of course, but an inner one as well. Godzilla here functions as a reason for the post-war veterans to show their worth, to push forward and make a life during the unlivable. As one character puts it, this is a war in which they’ll partake with the promise of life, not sacrifice. While this is a universal feeling, Godzilla Minus One is rooted in Japanese military culture. The concepts of the kamikaze pilot and “honorable death” are quite idiosyncratic, and thus merit that we watch this film with the Japanese experience of war in mind. Japanese soldiers not only had to deal with the horrors they experienced, but also came back to a ravaged country. To add Godzilla to this very specific situation, Yamazaki seeks to provide an anti-war message but also a statement on how Japan failed its soldiers who were expected to sacrifice body and soul for their country. Heroism in this film comes from living for one’s future, not from dying for one’s country. PTSD and hopelessness are front and center, but the film handles these themes delicately and thoughtfully. It is an empathetic and hopeful view of life after war that, though potent, gets bogged down towards the end when the message threatens to take over the film. But carefully placed dialogue, an emphasis on human triumph, and a climactic battle with the king that will not soon be forgotten, make Godzilla Minus One a masterclass in how to find humanity within monstrous horror.