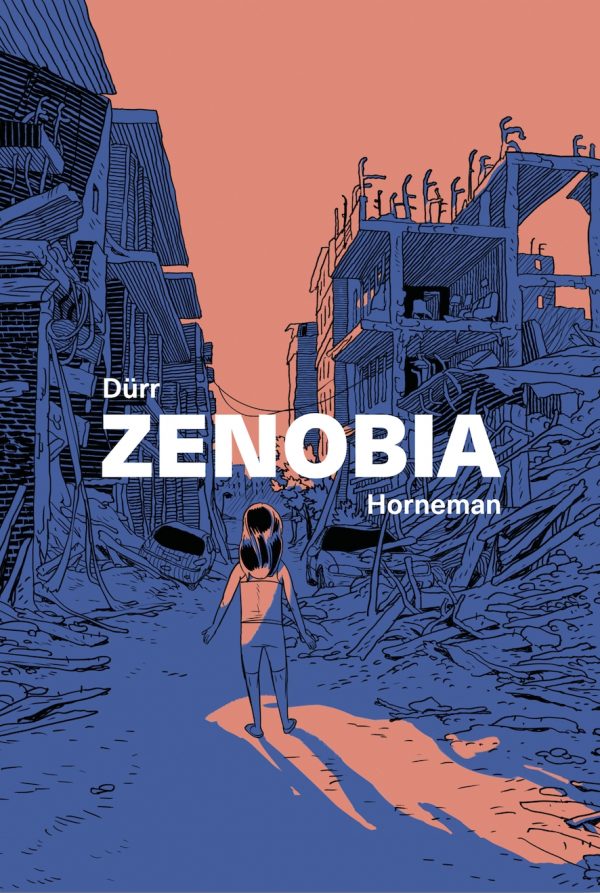

This beautifully-wrought and completely devastating Danish graphic novel will probably make you angry. Or at least it should make you angry. Most possibly it’s about something that doesn’t affect you directly other than having to endure the anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim rhetoric that has become more accepted in our own country, though has never been completely taboo. It’s a brief book that packs a wallop of emotion of its own, especially anger.

More than anything, Zenobia is the story of what happens when groups of people lose compassion for strangers. It’s the story of how things play out when difference is made the primary arbiter of how you qualify the worth of people. It’s a story that so many of us are in some manner, directly or indirectly, complicit.

Following the experience of a Syrian girl named Amina, the book opens on a crowded refugee boat, first presented as a speck in the sea upon which multiple human lives are crammed. It’s a simple expression of how in control of their own lives these people, adrift in the water without the smallest comfort, rustled together to become a single body of helplessness surrounded by a natural body that has no emotion toward them.

And then we begin at the end as rough waves send Amina flying into the water, submerged we find out how she ended up drowning and alone. In simple, gentle detail, some of the ugliest situations involving humanity unfold on a personal level. We find out more not just about Amina, the character in this graphic novel, but all the Aminas we cannot imagine for ourselves. Too many Aminas.

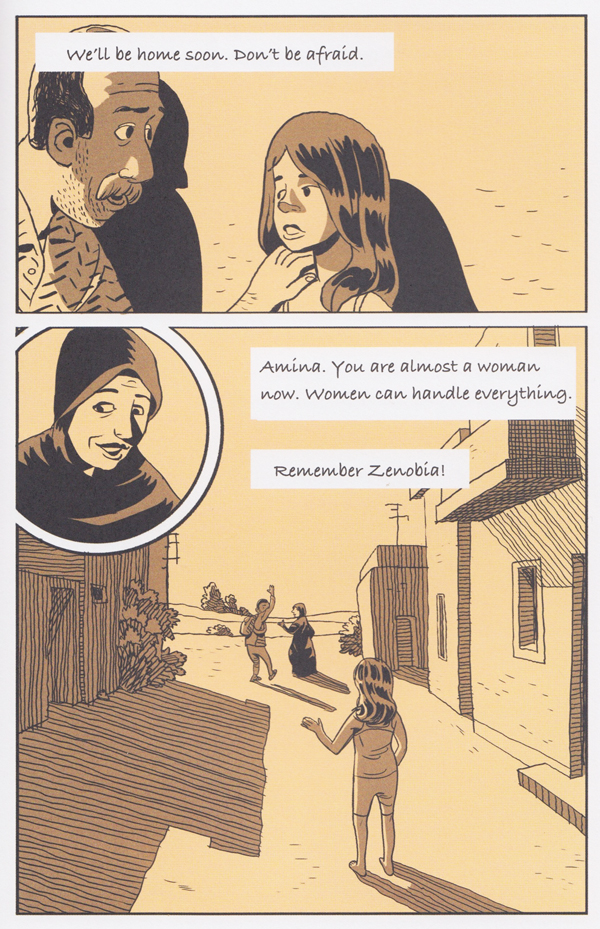

Author Morten Durr wraps in the legend of Zenobia, the 3rd-century Syrian empress known for her fierce warrior qualities and her expansive humanity, progressive for the era she lived, around Amina’s story. Presented as the ideal for Syrian women — though she could truly be an ideal for anyone that wants to operate with morality, intelligence, and compassion — she is evoked as a model of strength for Amina as the darkness envelopes around her.

But in this context, Zenobia might be, at worst, a false promise, at best a comfort during loss. The story of Zenobia can help Amina through her hardships, can soften the blows, can inspire her to hang on longer, but these are all efforts against the inevitable, because we, the reader, know all too well that what Amina is up against is much bigger than what perhaps even Zenobia was up against in her own time. Zenobia had clear foes. Amina is a speck being threatened by a large specter of hate and indifference.

The book is obviously meant for younger readers, but it’s certainly a challenge to take an incident like this and translate it suitably for that age group. It’s dark, for certain, and I wouldn’t want the darkness to be expunged from the presentation, but you also don’t want the darkness to become so overwhelming that the messages are obscured by the stress of what the book presents. Lars Horneman’s art goes a long way to making that happen. Deceptively simple and enormously friendly, Horneman is able to present a bleak situation in a way that matches the poetry of the words and which does not obscure the horrible aspects of the story.

There is power in simplicity, especially when that simplicity is utilized to contrast something so complicated. In the end, the complication has nothing to do with our human concerns, nothing crucial anyhow. A situation where humans are dying is as simple as that. The reasons very often are that other humans are allowing it. Simple. It’s certainly simple in the context of Amina’s story and the solutions, in that way, seem simple as well. Humans need to stop acting like humans and strive to be a higher creature. Zenobia may only be a dream for Amina, but she’s a worthy dream to have and the world would be better if more of us shared that trait with Amina.