In a world where mass audiences are starting to appreciate the out-there horror work of Jordan Peele (Us, Get Out), Ari Aster (Hereditary) and Robert Eggers (The VVitch, The Lighthouse), Peter Strickland’s work mays still be a little TOO out there for the masses.

The British filmmaker’s latest, In Fabric, stars Marianne Jean-Baptiste (Broadchurch) as a lonely woman wanting to get back on the dating circuit. During a random visit to a dress shop, she’s coerced into buying a striking red dress for her first date, but things aren’t what they seem. When she tries to throw it into her washing machine, the device systematically falls to pieces and other strangeness happens. Much of it ties back to the shop where all sorts of weirdness is taking place, some of it involving Game of Thrones’ Gwendoline Christie as one of the store’s odd mannequin-like staff.

Put it this way. In Fabric is not for the light of heart or the casual moviegoer, as Strickland has consistently proven that his horror influences go far beyond the Hammer horror and Giallo of so many other modern horror filmmakers. Some of those influences are fairly esoteric and underground, but it helps make his films far more unique and memorable.

The Beat got on the phone with Mr. Strickland for the following interview:

(Note: There is one particular SPOILER that is very clearly labelled midway down.)

Peter Strickland: It started with the shops, really. I wanted to get away from film a little bit. I felt like I really didn’t want to repeat myself and have this kind of approach where you can spot the reference. There are some references, but I didn’t want to be so heavy with it. I was quite heavy duty with it on the last film. I remember there this shop I used to go to as a kid called Jackson’s in Reading, which is a really flamboyant, theatrical place. It’s kind of steeped in artifice. I thought I could go back to how I saw those kinds of places when I was a kid, when you don’t understand a lot of things. You don’t understand where the dumb waiter leads to. You wonder if mannequins bleed, so this childhood curiosity – even though I’m not making a kid’s film, far from it – but you’re still employing that perspective. But then going to second-hand stores, buying clothing, finding stains on that clothing, smelling B.O. under the armpits… from someone who is probably dead, for someone you’ll never know what they look like. You’ll never know what they did when they wore that. It kind of activates the imagination. It really led into this very inherent courting power to clothing, which also led into other things like fetishism, body dysmorphia and still keeping in mind that I wanted to make an entertaining genre film.

There’s a danger of becoming this message film about consumerism, which was not what I wanted. There was a satirical element to that, but I didn’t want to make anything didactic. I don’t regard the main characters as consumerists. You have that in the background with the looting and the shoplifting, but not with the main characters.

THE BEAT:Were there a lot of British horror films from that era that inspired you over the years? The movie also has an anthology feel to it.

Strickland: I never saw that, actually. I remember interviews with him talking about it, but I never saw that film, no. A few films but nothing overt. There was Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Soulsin terms of the atmosphere, there was the M.R. James BBC adaptations, William Klein’s Who Are you, Polly Maggoo?, but you were mentioning anthologies and that was a big part of it. The first script had many more victims, but no one would fund it with that many victims. It had to be cut down. Initially, it was going to be going from victim to victim to victim. I could have kept the six victims by cutting the story down, but when you cut the story down, there’s a danger of the characters feeling disposable, that you don’t actually care about them. It was very important to feel their loss when the characters go away, and the only way I felt I could do it was to spend time with them, to see their hopes and fears and frustrations and so on, and desires, of course.

[NOTE: The next question and response have pretty MAJOR SPOILERS for In Fabric, so we recommend skipping over them until you have a chance to see the movie.]

THE BEAT: It’s surprising because we do follow Marianne’s character for quite some time, and we assume the movie is about her, so it’s surprising when it shifts to another main character.

Strickland: But that was the thing, just so you spend enough time with her at work and with her son and understand why she buys the dress. She’s not buying it because she’s a consumerist. Anyone would buy a dress in that situation. There’s nothing wrong with retail therapy to some degree. I wanted that feeling of when she dies, like when your pet cat dies and your uncle buys you a new cat. “Oh, okay. I have to get used to a new cat.” It’s a bit of a shock to the system, isn’t it?

[SPOILERS OVER.]

THE BEAT: You don’t realize the movie has that nature to it, but what about casting Marianne, because she’s been in so many British films and television including Secrets and Lies. Did she have any trepidations about doing a genre film at all?

Strickland: She didn’t say that, but I guess she would have had. I love Marianne, but she kind of keeps herself to herself, which I respect a lot. Yeah, when we offered it to her, it wasn’t an instant, “Yes, I’m going to do this.” I think she’s just someone who takes her time. She considers things, which is fine, but she never really expressed, “What the hell am I doing here?” (laughs) which wouldn’t surprise me with some of the scenes we did. But I was very happy she did it, because in the UK, we associate her with Mike Leigh, which is a very different kind of filmmaking. She was doing a lot of serious films. I know she had this part in Robocop, but here, she’s playing the lead. I do see this as a genre film, so of course, I was worried she’d say, “No,” of course, it was on my mind. I’m very, very glad she said, “Yes,” because she truly, truly elevates the film.

THE BEAT: It’s similar to when you had Toby Jones in Berberian Sound Studio, when you had this pretty respected British actor doing a very genre-driven film, but he elevated it, as with this one, since it was interesting casting.

Strickland: I think what it is. When I’m writing genre, I guess I’m fascinated by this tension between tropes of genre, the artifice of genre with human emotions. Even though genre films have human characters in them, let’s put their emotions in some kind of baffle with the more entertaining elements of genre. Let’s have that tension. That’s what I’m fascinated by. I think having actors that are really solid, good actors, that can make you believe in them, that was really a huge part of why I was doing this. I love both personal human filmmaking but I also love trash cinema and genre filmmaking. I don’t like this term “elevated genre,” because it implies genre is not that. I’m just trying to do something different. I’m not trying to make it better or worse; I’m just trying to make genre differently and have that tension, that struggle with real life. Real life competing with genre and you see what comes out of.

THE BEAT: I wanted to ask about casting Barry Adamson (an original member of Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds!). Has he done a lot of acting, and I didn’t know about it?

Strickland: I think it’s his first feature film. I think he might have acted in a few short films. That was interesting. I was really inspired by people like Joanna Hogg and Nicolas Roeg, who would use musicians, like Hogg using Viv Albertine, Roeg using Art Garfunkel, Mick Jagger, David Bowie and so on. I just had this conversation with Shaheen [Baig, the casting director], and I didn’t want to go to the same people, and she said, “What about Barry Adamson?” I was aware of his music, of course… “Oedipus Schoedipus” and his work with the Bad Seeds and so on. As soon as she said it, I thought, “That’s great,” and luckily, he had seen The Duke of Burgundy, so it was not a hard sell. It was slightly risky, but then again, he’s a performer. You always feel like musicians/performers, they must be able to translate what they do onto the big screen.

THE BEAT: Also, the music in this one is great, and you worked with another band I’m not familiar with called “Cavern of Anti-Matter.” Was that created for the soundtrack or was that an existing group?

Strickland: It’s an actual group. They already had two albums out before they did the soundtrack. I guess Tim Gane, from the band, his band before were quite well-known in America. He was in Stereolab, and weirdly, they’ve just come back from this American tour, so they’ve kind of reformed. I’ve known Tim’s music since the early 1990s. I was a huge fan of what he was doing and his ideas about sound, his ideas about film as well. I met up with him. It was a very organic thing, because I didn’t have a film at that point. I think the danger in the past was I’d write scripts, and I’d listen to music and I became very attached to the music I’m writing to. It’s very dangerous if you ask bands or composers to make a piece of music similar to what you’re listening to. It hinders them, and it becomes very redundant. The trick was to get music in the very beginning even before I had an idea, so [Tim] was sending me very long 18-minute demos, stuff like that, which were quite droney. I think a lot of the writing for it, just came from that. It was a very different experience but very enjoyable actually.

THE BEAT: You mentioned before that you had other stories for this but you cut it down to two. You don’t really get into where the dress came from originally. You keep it a mystery, so is there more to this premise that you might want to explore someday?

Strickland: If… if… a very big if. If I ever did a sequel, there was the temptation to go into a backstory. It’s always tricky because you lose a sense of menace. You lose some mystery if you stay with it tomorrow. I think it’s fairly clear that the staff are behind this whole curse. I kind of saw it a little bit like Frankenstein’s Monster. There’s something bigger than what they’ve bargained for. It’s much more destructive than they bargained for, so whenever it comes back to the store, they’re just terrified of it. “Just get it away, get it out of here!” In a way, it served the whole idea of the sales, Black Friday in America. Just get it out, get rid of it! (laughs) Everything must go! Obviously, we have hints of what’s going on with these rituals which involve body fluids and sex magic and so on. I didn’t want to be too emphatic with it all. I think the element of randomness with the dress. It’s this irrational force is much more in tune with the film being a nightmare.

THE BEAT: What was this other thing you had been trying to get going? Is that also a genre-type film or do have other directions you’re interested in travelling?

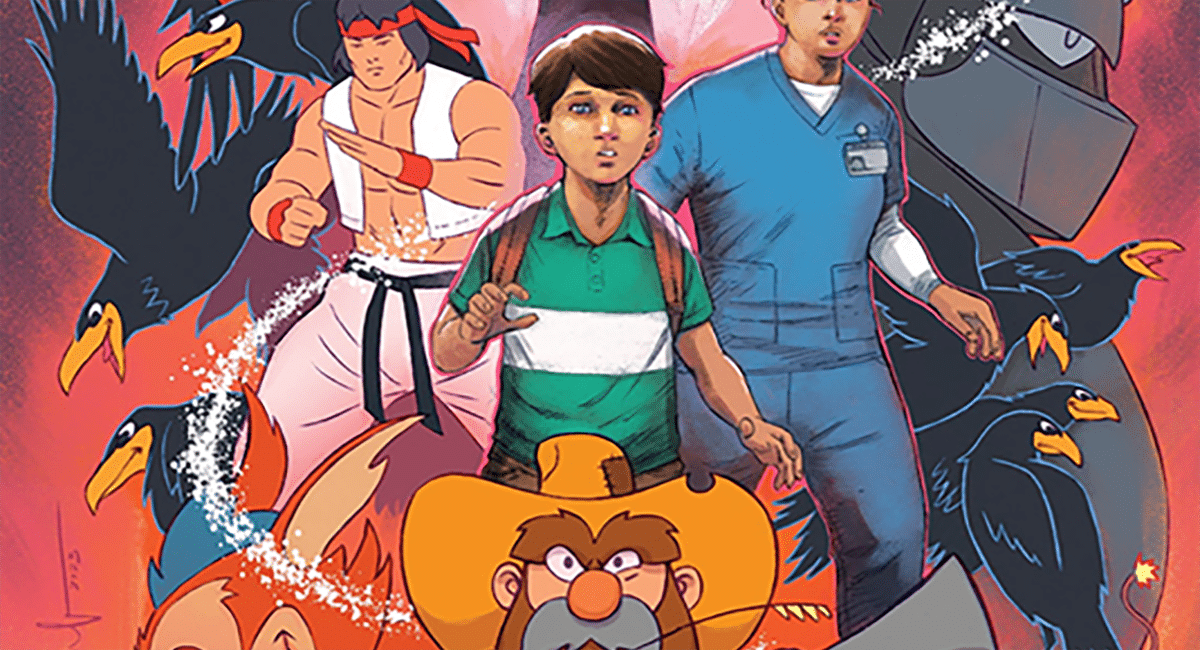

Strickland: Well, it was a dark film about food with Fatma Mohammed… As always, she’s in all my films. We were going to shoot it in August, but it just kind of collapsed, as these things do. I’m working on a kids’ film as well. I have three films I’m working on, and the other one is called Night Voltage, which I’ve been talking about for eight years now. It’s set in New York in 1980 in the last days of male on male hedonism. I guess I was watching a lot of gay pornography from the ‘70s, things like Wakefield Poole especially, Fred Halsted, Peter de Rome, Jim Bidgood – really psychedelic gay porn, which was really unlike anything else, just really mesmeric and hypnotizing and using multiple projections and dry ice and mirrors. I guess that was the cinema I really want to be inspired by. There’s something I like about porn where it’s always kind of discarded. People are immediately repellant and don’t want to deal with it, so I guess I have this scavenger mentality. (Laughs) If it’s in a bin, it must be interesting.

In Fabric opens in New York and L.A. on Friday with a special screening at the Metrograph in New York Wednesday night and Strickland doing QnAs all weekend if you have any further questions.