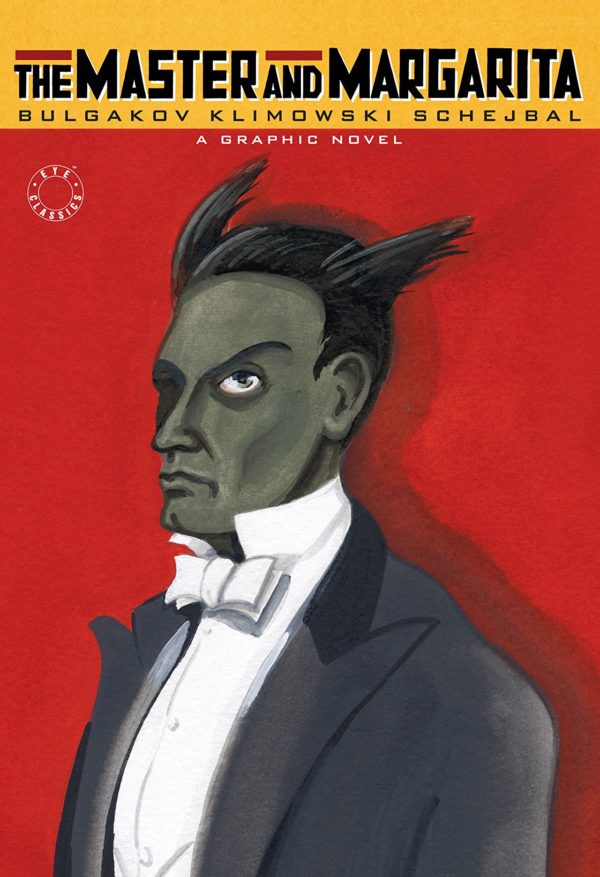

The Master and Margarita

Written by Andrzej Klimowski

Illustrated by Danusia Schejbal

SelfMadeHero

As a choice for a literary adaptation in graphic novel form, you couldn’t get much more obscure or curious than The Master and Margarita. This surrealistic Russian satire written over a period from 1928 to 1940 points its finger at, among other things, the literary elite of Moscow during the era, a real-life foil for the author, Mikhail Bulgakov, who experienced rejection, ostracism, and censorship from that body and the Russian government during his life — which ended in 1940.

The Master and Margarita was considered by the author to be unpublishable since it was obviously subversive material, and the manuscript survived through the decades as a secret knowledge kept protected by a small group of admirers. It was finally made public in censored form as a two-part presentation of the magazine Moskva in the late 1960s, and then appeared in its complete original form in 1973, after which it was declared a 20th Century masterpiece. Though well-known in Russia, when you read accounts by admirers of the book outside of that country, you encounter a group of people who felt like they had entered some kind of secret society through their knowledge of this book that was so obscure as to seem hidden away.

The history is obviously fascinating and Bulgakov himself seems like the prototype of the heroic rebel fighting against the state in the name of creative fiction. He was banned from publishing because of his subversive material and Stalin himself refused to let the writer emigrate out of the country. He confined himself to writing subtle critiques of Stalin and his government for the Moscow Art Theatre and writing books in secret. The only thing that could stop his rebellion was inherited kidney disease, which his father also died from.

Given such an amazing backdrop, The Master and Margarita is surprisingly unassuming. I don’t mean that as an insult, except maybe to Stalinist Russia, as one of the greatest snowflakes in history. How this oddball little book could possibly be of any great danger to the system is beyond me, but then again, maybe Stalin could recognize instruments of downfall better than I can.

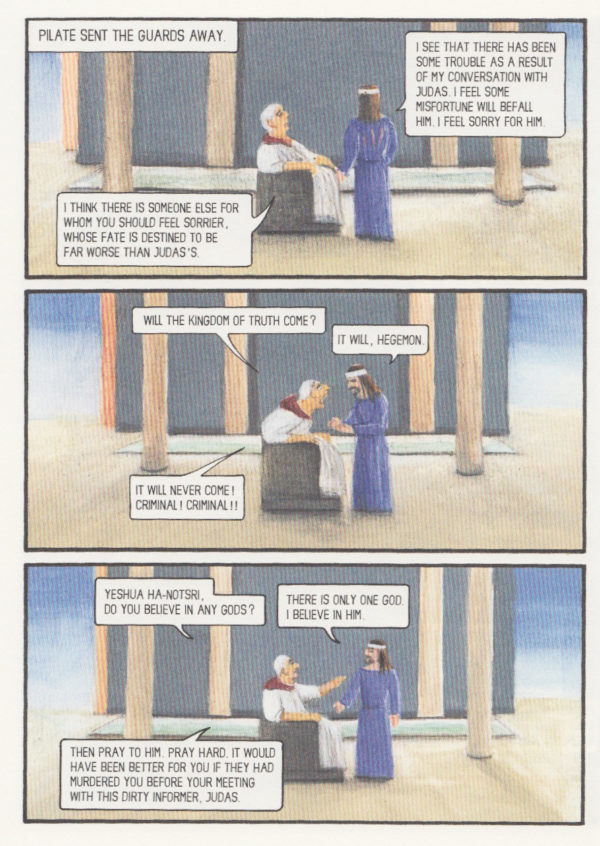

The story is a multi-leveled one. Part of it involves a writer who is named the Master by his lover Margarita, and who writes a novel about Pontius Pilate that is rejected by Moscow’s literature elite — part of the autobiography, obviously. There are also sections taken straight out of the book, beginning with a sequence of Pilate conversing with an about-to-be-condemned Jesus and then revisiting in the aftermath of his crucifixion and Pilate’s views on Christ’s philosophy, his followers, his fate, and the Roman hierarchy.

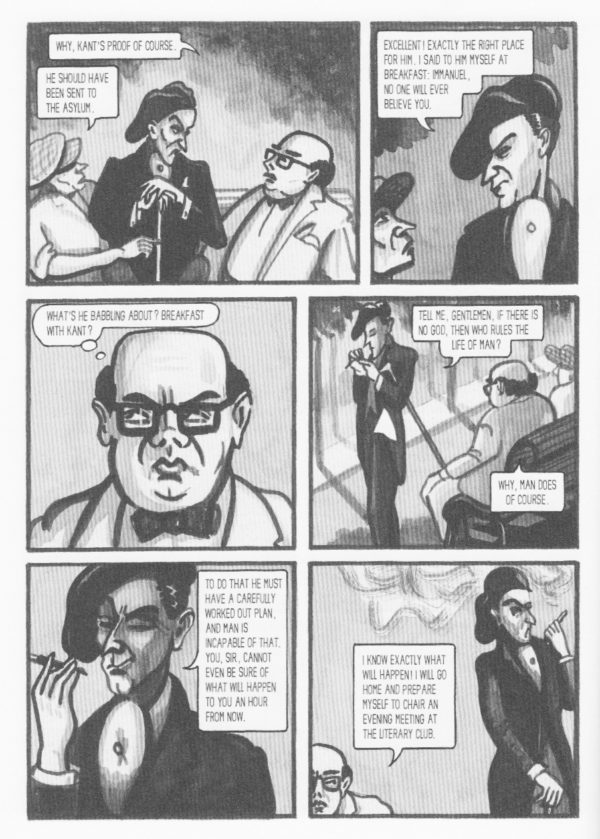

Much of the action in the book centers around the Devil, known as Woland, who appears to be targeting the same Moscow literary society, predicting the gruesome death of an editor and making an appearance in a theater causing havoc as a magician and professor black magic. Several creatures follow him around as he brings chaos to the literary world and sets forward several instances of ritualistic magic practices that all work their way towards an ultimate purpose that brings together the experience of the Master and his story of Pilate with various other elements of the story.

This is unmistakably a work of its time, but the chaotic events that take place in them undoing the systems that man has set in place also speak to what has been lost in the last 100 years of western society, which has clung to the orderliness that the early 20th Century and movements like communism, socialism, and fascism all sought to impose in one way or another. Democracy is a free-for-all by comparison, but the Devil’s game is not exactly that, an even if you were to call it anarchy, it wouldn’t factor in the collective decision making aspect of it. No, what the Devil as Woland is doing is undermining what the humans in the story wind their egos around, what they look to as assurance for the way they live. By singling out the Master and what he offers in his rejected book, the Devil is tearing down their privilege and transforming it into hubris.

That’s exactly what Jesus did, but in the Master’s stories, Pilate was not quite the Devil. He was almost there, though, and there is a scene when following Jesus’ death, Pilate offers the disciple Matthew a job in a library, cataloging the scrolls, but with the implication that there might be an opportunity to relating to Jesus’ ideas, perhaps preserve the disruption.

To me, that seems to be a lot of what The Master and Margarita is suggesting, that disruption by the artist is one of the highest callings there is. And in Soviet Russia, I can only imagine this was a compelling and important statement. It still is in 21st Century America, when disruption is generally vapid and without nuance, and so much creative work is in service of capitalism. Andrzej Klimowski and Danusia Schejbal stay focused on keeping the adaptation not only true to the original work but also reflective of its time, but they aren’t blind to the relevance of the book in modern-day. As clearly stated in the foreword, Bulgakov’s story declares that “there is no bureaucracy that can truly crush the human spirit, and they have no power over death.” Their adaptation furthers these truths.

One of my favorite novels—this is exciting!

Comments are closed.