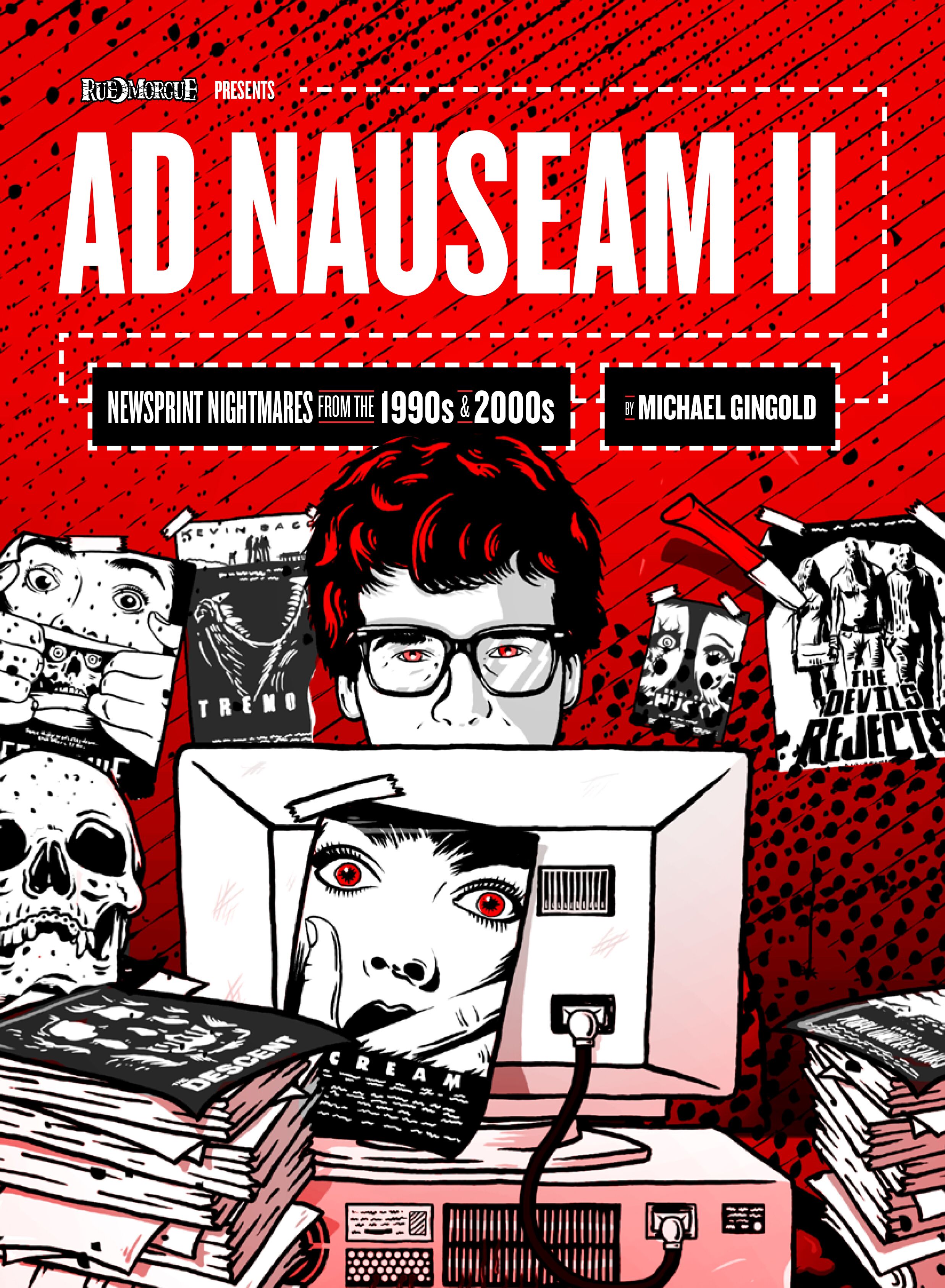

Long-term projects have such a mythic sense to them. It’s not just about the final product but also about the creation process, how everything was collected put together. Michael Gingold’s Ad Nauseum II: Newsprint Nightmares from the 1990s to the 2000s is a fascinating read for these reasons and so much more.

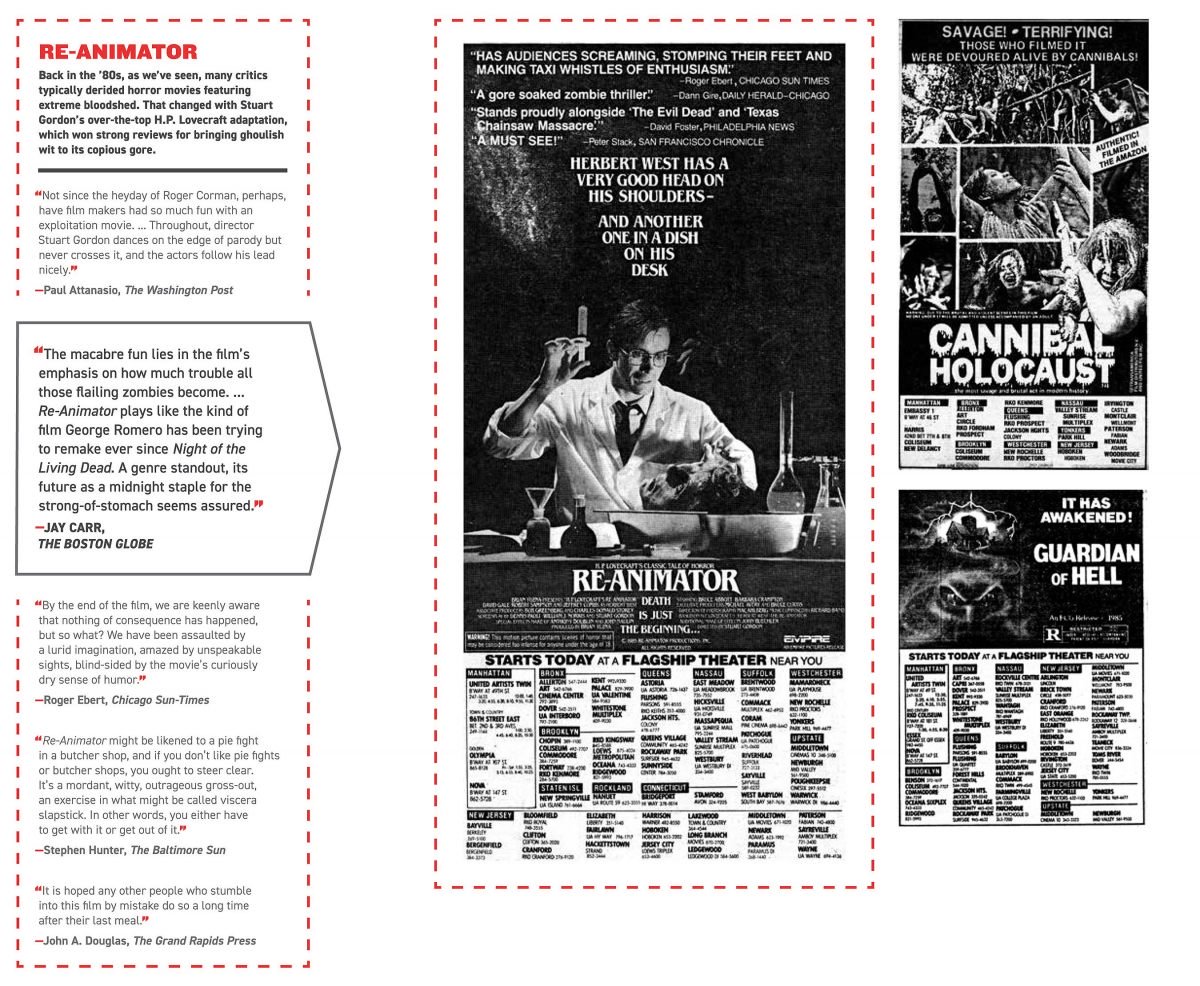

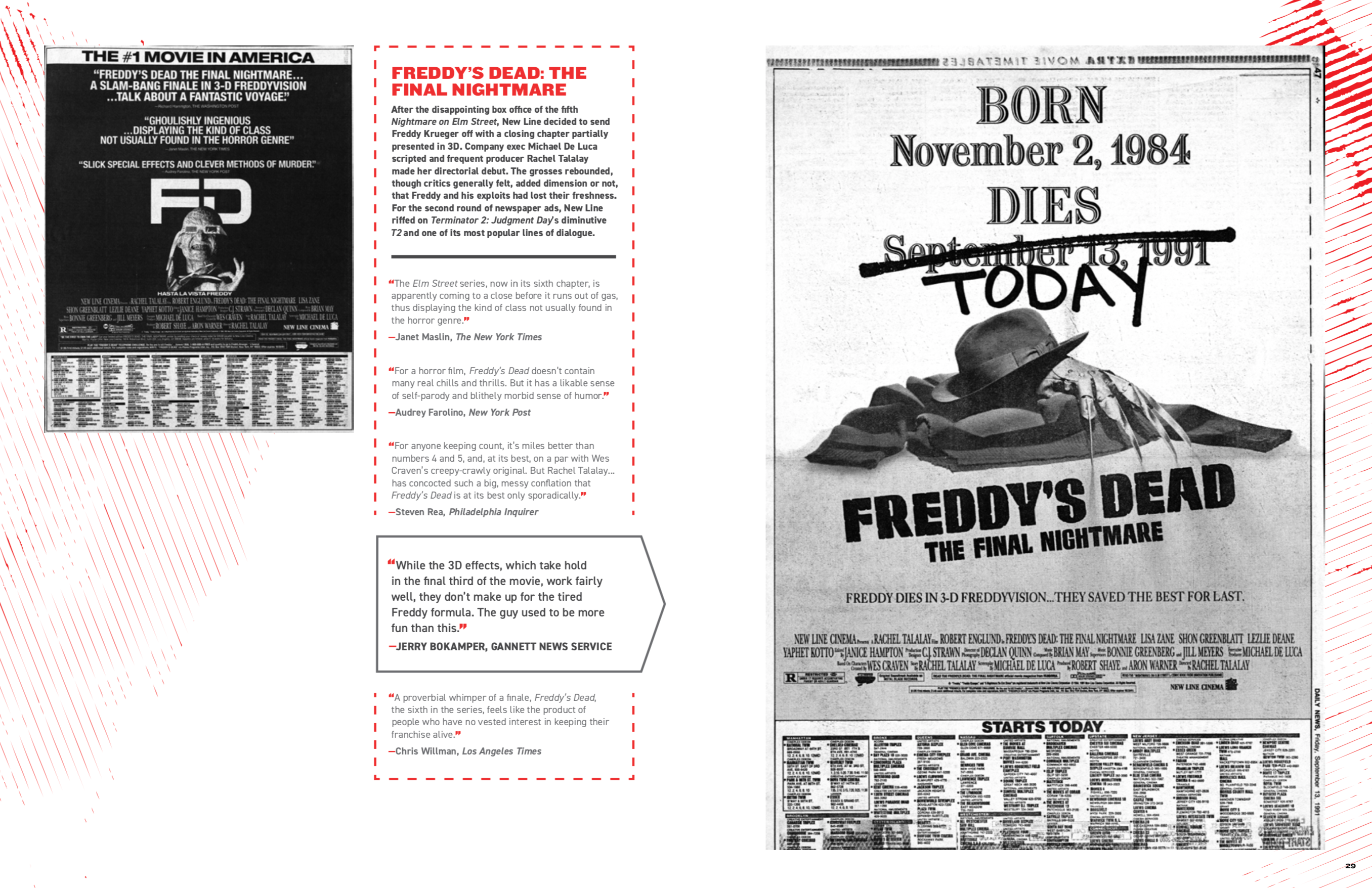

To hold the book in your hands feels like holding a rare artifact possessing secret knowledge about some of the ways horror tried to get eyes on movie screens during the early 90s and early 2000s. The collection of newspaper clippings found in Ad Nauseum II comes out of Gingold’s lifelong fascination with horror movie ads and how they changed, where they were placed, and how they were presented to readers before the internet came and started homogenizing ads.

The book goes through the many shifts horror went through in the time periods previously mentioned. It goes from the slasher revival to the rise of torture porn and even into the arrival of the found footage sub-genre. It’s a fascinating ride down memory lane if the road were made of sharp objects and scattered body parts.

Ad Nauseum II follows Ad Nauseum: Newsprint Nightmares from the 1980s, which looks at horror movie ads from the 80s (as the title clearly states) while also showcasing oddities and obscure films such as Psycho from Texas and Dracula Blows His Cool. Gingold took the same approach to science fiction movies in his book Ad Astra: 20 Years of Newspaper Ads for Sci-Fi & Fantasy Films, which centers on movies released in the 1980s and 1990s.

The Beat caught up with Gingold at New York Comic Con 2019 to talk about how years of newspaper clippings resulted in several books about horror, scifi/fantasy, and the lost art of newspaper movie ads.

Ricardo Serrano: Your book is so unique, so specific in its take on newspaper ad campaigns for horror movies. What was the thought process behind it? What did you hope to accomplish with Ad Nauseum II?

Michael Gingold: There’s a lot of nostalgia behind it. This is back in the time when people didn’t have internet and everything was promoted in entirely different ways. Back then, there’d be the excitement of looking at what opened in the movie theaters every Friday. Some movies didn’t even have television promotions, so the newspaper ad was the only thing accounting for its existence.

There were also a lot of variant ads. Sometimes it varied from city to city, other times by week, especially in the 80s. Also, they can connect directly with people who lived in the areas found on the ads’ showtimes schedules, showing which movie played in which theater. People can remember the time they went to watch a certain movie at a certain location based on these ads. We’ve now lost that in the advent of the multiplexes and digital information.

There’s different levels of nostalgia at play in this book and it’s just not something you can simply get in today’s ad culture.

Serrano: What was the research process like? I mean, it feels exhaustive and comprehensive. Did you start collecting these ever since you were young?

Gingold: Yeah! I started collecting when I was twelve. I just got really obsessive with it. You’d get a new horror or science fiction movie opening every week. Every weekend I would go look at the paper and see what was there to collect. I think there were two summers where I missed some because I was away at summer camp.

Serrano: Is this a type of book you could do now without having years of clippings already collected?

Gingold: Well, the resources are there and there’s all the stuff you can find online, but I feel that’s kind of like cheating, in a sense, if that’s not too presumptuous. There’s something to just having the actual ads and then reproducing them. Some museums have high-res scans of newspapers, even of the bigger double-page ads from papers like The New York Times. Conceivably, you could do it off the internet. But again, it’s not as pure as having the actual ads there in front of you. Also, going about it just off the internet will take a lot of time given you have to go paper by paper in the backlog.

Serrano: You mentioned one of your intentions was rooted in nostalgia, but when I was looking through it I also saw a visual history of horror as well. Did you think about it in these terms as well?

Gingold: When I was collecting them it was a kind of way to keep these mementos of movies I would go out and watch. Back then I didn’t even think this was something that was going to go away and now we basically have no newspaper ads, so it adds to its nostalgia value. It was probably in the early to mid-2000s when you started to see 20th Century Fox taking out smaller and smaller newspaper ads because everything was moving online. So I started thinking it would be cool to put them all in a book, especially the smaller ones, because that’s all that was going to be left of them. I thought it was a great way to preserve them.

Serrano: And they really look authentic. You can feel these were cut and collected.

Gingold: That’s what I mean. I mean some of them are faded and some of them are a little torn. Early on into the design of the book we thought of making the ads look like they were taped into a scrapbook, give it that feel, but it was a little too on the nose and distracting. So we stuck with getting the ads as high resolution as possible.

Serrano: I’m interested in the little tidbits of info you include with certain ads. I remember looking at the Candyman 2 poster and noticing a short block of text saying that the poster for itself, which was Candyman with his hook superimposed over an image of a white woman, was controversial because it came out during the OJ Simpson trials. How did those bits of story figure into the book?

Gingold: I felt like each of the stories I got on some of the posters were like lost bits of horror history. The Candyman 2 poster was something that stuck with me because it came out during the OJ trials. But I also remember when Sony and Dimension were suing each other over Scream and I Know What You Did Last Summer. It was a way to put these things into posterity. When cases such as these would come up on the news I’d also cut out the articles that spoke about them. So we have lots of reviews but also some backstory that a lot of people don’t know about.

I did a little research on some of these stories, but most of it came from my files. Even while looking through those files I remembered other stories that made it into the book. Not all of them are included. Maybe something to think about later on.

Serrano: Thinking about promotional posters, are newspaper ads considered as promo posters or are they two separate things altogether? As in, the poster is one thing and the newspaper ad another.

Gingold: It’s all part of the marketing campaign. During the 80s though, when there were more variant ads, you’d get new promo just to keep people interested a few weeks into recent releases. Some campaigns were tied to holidays like the Gremlins Christmas ads or the Chucky movies, where we see the evil doll carving a Thanksgiving turkey.

In some cases, especially with indies, the ads would be different than the official posters. Sometimes they varied by location. Different newspapers would have their own approach or have different promo sent out to them. Sometimes they would try out different campaigns to see which one worked better. For the movie Maniac, the NY Times couldn’t have images that were as gruesome as the actual tabloids, whereas The Post and The Daily News decided to show the killer with the knife and the woman’s scalp in his hand, drenched in blood. The Times only showed the killer’s feet in a pool of blood and a whole lot of black background.

Serrano: How do you see these variants in today’s market? I mean, it wasn’t until Mondo and other companies started creating limited edition posters for movies that we got variants, which come with a higher price tag due to them being marketed as collectibles as well.

Gingold: It’s really interesting that we’re getting some of that back. It really is a callback to the days when we used to do that, have different posters for the same movies. On the other hand, what I hear from a lot of filmmakers is that what studios want is a poster that looks good on a thumbnail or a VOD cue. It has to be a face or a very identifiable image. I’m thinking of the Fright Night poster and how busy it was as a piece of promotional art. It wouldn’t be approved as the official poster for the movie if it were to come out today.

Serrano: In that sense you can say older posters told a story about what the movie was to be about while today’s posters are little more than teasers for each movie.

Gingold: That’s a really good way to look at it. The posters did tell a story. They don’t now. Look at what we have a lot of today, posters of a woman being dragged into a dark background—which we see a lot of today—and upside down houses, which we seem to be getting a lot of as well. Taglines are a lot less interesting now. Through the 90s you had a lot of fun ones. Now they all sound the same. It’s almost like they don’t want to their movies to look distinctive.

A lot of this is becoming so homogenized because there’s so much product out there. I think a lot of people just don’t want to alienate audiences with something that looks and feels too different.

Serrano: Thanks for the chat!

Gingold: Thank you!