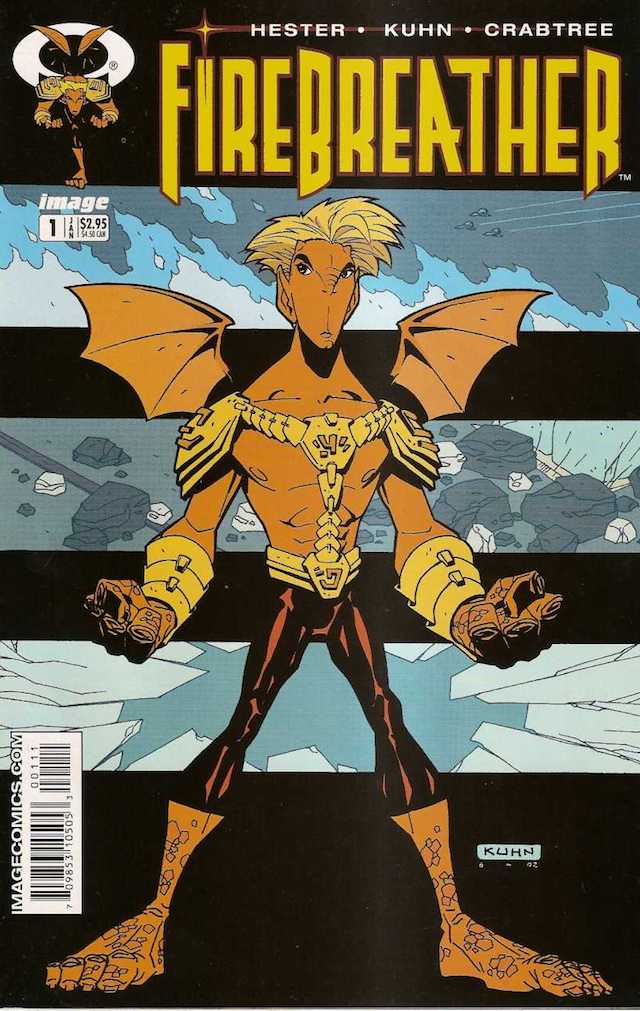

Phil Hester has been one of my favorite artists for a long time, with a style that feels suited for any kind of story, from the silliness of Irredeemable Ant-Man all the way to his eery and melancholy work on his latest title, Shipwreck. In addition to drawing Shipwreck and memorable runs on superheroes like Green Arrow and Swamp Thing, Hester has been writing books for a number of publishers, including titles at Image like Firebreather and Mythic. I was curious about how Hester manages his careers as both a writer and artist, so I was excited to get to interview him. We discussed how writers might view his art differently than he does, why he rarely both writes and draws, plus much more.

You’ve worked with a number of renowned writers over the years, including Kevin Smith, Brad Meltzer, and, most recently, Warren Ellis. Have your collaborations with them as an artist influenced you as a writer?

Certainly. I’d have to be a stump not to learn at least something after working from these writers’ scripts. I’m not sure I can trace any specific element of my work back to their influence directly, as I’ve been writing my own comics since I was a teen, but I can say I’ve picked up a lot in terms of how to effectively frame the stories I want to tell. I mean, I don’t want to tell exactly the same kind of stories as these writers, but I have learned how to be a more compelling writer from them.

What has reading scripts that writers tailor towards your style taught you about your own art?

[Laughs] Well, sometimes what I like about my art isn’t necessarily what others do. I don’t feel like I’ve ever been typecast in any way, mostly because my style is such a mess no one can put a pin in it. I like to think most writers trust my storytelling skills and tend to give me a little room to dig into a story and pull out visual themes and unspoken interaction that enrich the script. I like to think they’re in the hands of a competent director, so they give me some leeway to change shots and beats here and there.

Was it difficult to get noticed by editors as a writer as well as an artist?

A little bit. It works both ways. Most editors who see me as a writer don’t think of me as an artist either. I just think different people prefer different aspects of my work. It might be a generational thing. The people first exposed to my work through my art might see me as an artist no matter how much writing I do. The few who dig both aspects of my output are gold.

You’ve had prolific careers as both a writer and an artist, yet you rarely both write and draw a book. Can you say why that is?

Most of my writing is creator-owned, and I try to cast artists for those books who fit the style of story I’m trying to tell. I try to be impartial about my own skill set. If I’m not right for a book, I’ll go out and find someone else. That frees me up as a writer, too. I’m not out here limiting my stories to just stuff I can credibly draw. I can’t imagine myself drawing The Coffin or Firebreather now that I’ve seen what my collaborators have done with them.

Your style, while extremely versatile, is particularly effective with humor. Do you gravitate towards books that have comedic elements?

Not particularly. There’s an intractable bounciness to my work, even when I’m doing some dark stuff. By the same token, there’s a darkness to my lighter work. Like I said, I’m a mess– a planet with Joe Staton at one pole and Bernie Wrightson at the other. Maybe that’s what’s interesting about my stuff. There’s always a left turn in the middle of it. My beautiful superheroes have an edge of ugliness. My monsters have recognizable, fragile humanity.

It’s certainly no conscious decision of mine. It’s just the way I draw. I’m the product of my influences. I guess it’s like life. Nothing is 100% serious or humorous. It’s always a mix. That makes it relatable, I hope.

Have you considered making a strip in the vein of Peanuts or Calvin & Hobbes?

Sure, but that’s such a hard nut to crack. I think I’d rather do a one-panel like The Far Side, but if I had to do a strip I’d like to do something that harks back to the classic adventure strips of Caniff or Robbins– noirish high adventure.

Every year, on Jack Kirby’s birthday, you do 100 sketches of characters he created to benefit The Hero Initiative. What prompted that?

HERO does an event every year on Kirby’s birthday called Wake Up and Draw in which artists around the world draw a Kirby character and offer it up for auction to benefit The HERO Initiative. These pieces are breathtaking. I wanted to play along and help HERO but knew I could not compete with most of these masterworks. On Kirby’s 97th birthday I had the idea of doing 97 simple sketches and offering them up to folks on twitter, worrying that I wouldn’t get 97 takers. Well, orders filled up pretty quickly and I wound up doing 97 sketches of Kirby characters over both my birthday (the 27th) and Jack’s (the 28th). These were mostly just head sketches, but it still proved almost fatal to pencil and ink them all by myself. The next year I enlisted help from many of my inkers like Eric Gapstur, Bruce McCorkindale, Ande Parks, and more, and we managed to grind out 98 Kirby sketches, this round a bit more involved than the last. Each year the sketches got more detailed and the money raised went up accordingly. It all climaxed on Kirby’s centennial when we did a live event sketchathon at Krypton Comics in Omaha to produce the 100 sketches. It was exhausting but raised a lot of money for HERO.

Has drawing so many Kirby concepts for the last several years given you a better understanding of his art? If so, what have you learned?

He trusted his imagination more than any other American cartoonist. If something felt right to him, he went at it with unmatched vigor. You can see it in his dynamic drawing style, but I think it’s even more evident in his concepts. He put no limits on himself. His drawings are not accurate depictions of human forms; they are beyond accuracy. They depict the inner lives of the beings he draws– the angels and demons wrestling inside all of us are visibly wrestling in the push and pull of Kirby’s outrageous anatomy. The life force at our core flares out like a supernova from Kirby’s creations. He doesn’t create costumes, he creates second skins that display the soul within. As magnificent and daring as his drawings are, they are just vehicles for the even grander, bolder concepts they embody.

At a time when a lot of artists have transitioned to digital, you continue producing physical art. What do you like about drawing on a board that you don’t get with a Wacom tablet?

For one thing, I like having a piece of art when I’m done. I’m an original art collector myself and I love the ritual of holding and studying art from another time. Secondly, I was trained in art school to get lost in a drawing, to battle it, to lose it and get it back. That battle doesn’t happen when you can simply undo your last move. I need to make mistakes, draw myself into a corner and then draw my way out of it. How I deal with those mistakes, how I improvise within them, is really the only interesting thing about my work. The page is just a record of my struggle. I’m not one of those artists who see an image in their heads and just transcribe it onto the page. I need to beat a drawing out of the ether, and for it to bite back as I drag it into existence.

You’ve never had a really long run as either a writer or an artist. Do you have a 60-issue epic you want to tell someday, or are you content working on series with a smaller scope?

I have things I wish were longer runs, but I did do both Swamp Thing and Green Arrow for 3 and 4 years, respectively. I do have a project that I plan to both write and draw that I hope last about 40 issues, but the marketplace ultimately decides how long your story is in the world of monthly comics.

You can follow Phil Hester on Twitter @philhester and view more of his beautiful original art here.

Matt Chats is an interview series featuring discussions with a creator or player in comics, diving deep into industry, process, and creative topics. Find its author, Matt O’Keefe, on Twitter and Tumblr. Email him with questions, comments, complaints, or whatever else is on your mind at [email protected].

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

Nice summary by an Artist that knows himself really well. What Hester said about his mixed and messing style is my experience of his work, and it has made it worth reading.

Comments are closed.