Story and art by Mari Ahokoivu

Translated by Silja-Maaria Aronpuro

Published by Levine Querido

Here is the story of a daughter who chooses to dance in the shadows of the woods. The story of her daughter, if bear is the violent finality at the center of nature’s cycle of birth death rebirth given form, fire is a further refinement of that story. Grandmother sky, dark tutor, when I said shadows I meant it, mouths open, teeth instead of eyes cut through the ink, the one with the hollows above its hips will find its way to anyone’s feet. A miserable mask more want than was, the black arms of trees reaching out through the snow to embrace the unwanted. It’s a fairytale nightmare of the highest quality, a heartfelt history lesson written in flames, a poem. Mari Ahokoivu has combined myth and maternity in her graphic novel Oksi, and it messed me up.

I think a bookshop glance would classify this as YA- depending on which pages you catch- the aesthetic, the publisher, but that gives you the reader (the ‘you the reader’ that isn’t reading this) that deception, shock, Skibber-Bee-Bye, when things take a turn towards creation myths and break hearts/spill blood. I wasn’t ready for the brutality that was coming from a book that was illustrated in the style of art gallery craft show handmade stationary sophisticated paint palette even if I was familiar with, y’know, what bears do when they aren’t sleeping cutely. However I think the magnitude of my shock speaks more to my preconceptions as a consumer than a choice made by the author. We’re definitely past the point where cute and scary are separate aesthetics — the contrast of their combination makes for good stories and bad but it’s definitely also established. There’s something different about Oksi that’s hard for me to put my finger on. It’s not that it isn’t consistently sweet and cute, it is. Ahokoivu uses techniques rooted in vintage brush skills and aesthetics that give the art age as well as softness, young bear old soul, and in that age is a permeating darkness that reveals itself in the read.

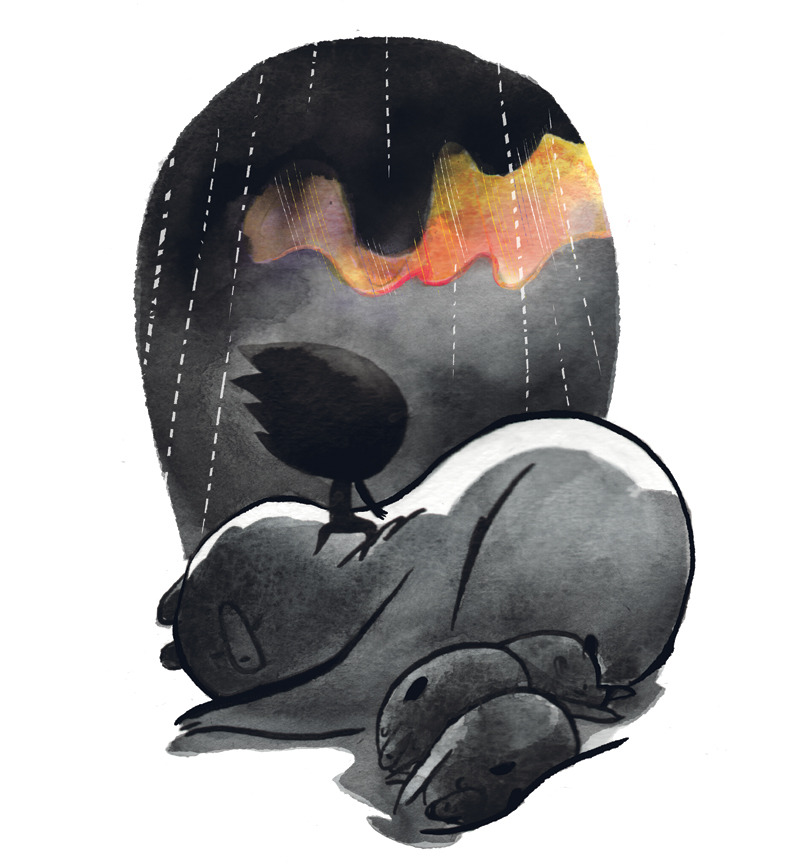

Stormy charcoal wash has all the bare power of black and white comic art, but within character and landscape Ahokoivu achieves layers of murk, smoke, and shadow. There aren’t a lot of other artists doing this kind of genre conflation — Zao Dao, Emily Carroll — and no one doing it like Oksi is. Amélie Fléchais’ work in reimagined folklore is the Dustcovers to Ahokoviu’s Cages. The curve in brush is the kind of expressive that only comes from control, the strong contour lines telling the style of the story as much as the gauzy layers of paint do (as well as its stark absence as snow and void). Bears and spirits and creatures are all so smooth and simple, shadow puppets cut with a bandsaw as much as a brush, the eyes points of white, powerful and perfect, no line out of place. More worked are the trees that edge the panels or float behind the action. The forest is the stroked ghost in monochrome complicating things. It’s clean and quiet, innocent even, a cute look, a twee book. Just a black bear in the snow, some cubs, some animals, night sky, stars, penumbra. To say nothing of the Northern Lights.

Black and white, gold for magic, red plays the part of blood with occasional bouts of burning, unpredictable intrusions of Aurora Borealis. White bark and snow frame the scene. Ahokoivu is a clever constructor of invisible gutters. This was one of the elements that immediately spoke to me when I picked the book up. I am deep enough into the comics journey that the ubiquitous cage of panel grid everything every time (or worse yet tallying them, madness) has caused me enough visual fatigue that stories told via sequential art that do it in a different way- unreconstructed- immediately go to the head of the class. You could put squares around what Ahokoivu did in Oksi; sometimes she does.

Often each moment or panel or whatever is isolated in white, like a clear cup being filled with art, the terrarium grown within an inverted cloche. Actual angles do form around the beats when the story calls for patterns, severity, or austerity. What is always bound is the language of magic. Speech adheres to the edges of the tail, balloons become scrolls, when black becomes gold history is revealed, a true story told. The golden word runes border the page and the story becomes the same, a golden truth told about the mystery before bear’s birth, before fire asked questions. Seriously, gold lettering equals spoken magic is working is such simple, instant, effective visual communication, pure comic book power. I said Oksi is vintage but really the take is fresh as it gets.

The read changes as it’s read. Regular reversals of perspective switch the roles of the gods and their daughters from good to evil, savior to antagonist. The bear and fire, sky and forest, it’s Finnish folklore, old and cold. But what it feels like is less Brothers Grimm or Charles Perrault and more mystical, gnostic gospel apocrypha. Genesis stories where angels and demons are both shapes seen in the pool. Are the imperfections of creation a reflection of their source or the medium through which they’re experienced? From these deviations comes a perspective more compassionate than nature’s (but still in tune with it).

The sacrifices that seem unjustifiable to us are just what the theoi proteroi do to each other. Families of the gods destroy themselves, present pantheon obliterating past without pause. On the other hand, Ahokoivu’s writing is human always. Reading about blasphemy is one thing and witnessing it is something else, and Oksi is a fight for life. There are hard consequences to wielding power irresponsibly, paired with an understanding that the powerful set the rules we play against. A mother’s life, her own, and a game between heaven and earth. Power creates with expectations and intentions, but without guidance? Deviation happens. But that’s also good? Folklore is great at telling broad truths with cryptic, unfathomable particulars. Flawed, if that’s what you want to call it, the temporal is still greater than the infinite. What must end, ends, and, particularly in these pages, even if it’s for the best it still crushes your heart.

Who can tell what’s for the best? What do leaf, bear, and flame know of innocence? Nature is resigned, what’s done is done. This is about guardianship versus parenthood. A metaphor made matter, still mostly metaphor. Light is the extinguisher of darkness and how shadows find their definition. Fire is the engine of creation, it’s irreversible consumption, it’s on most every page, but warm moments are fleeting, Oksi is more cold than snow. The story is endless foreboding, the splendid little bears and sweet fire child and their inescapable atmosphere of impending doom.

A book for more of those who dare to question god. Broken rituals split the sky door open with magic, the leaves blow on the isle of the dead, and it is up to us to honor those who have passed, the world forgets and the gods have their reasons. Why are we even born? Have you ever looked up at the Northern Lights? A family story, the old tale of children lost in the woods, and older tales still about older things, told like a folktale plain and hard and true. Mari Ahokoivu (and Silja-Maaria Aronpuro, who translated the English edition for Levine Querido) created a book that I’ve read more than once but still not enough to definitively put words to what it means to me. Oksi is as beautiful as it is gutting, I imagine I’ll be back in those woods again soon.

Published by Levine Querido, Mari Ahokoivu’s Oksi is in stores now.