The term “writing for your artist” gets thrown around a lot, but is rarely defined. Developing a relationship between a writer and artist of a comic is incredibly complex, considering the many ways creators can collaborate on a comic. What does it truly mean to write for an artist? That topic merits deeper examination, and this piece was written to provide that.

Do writers and artists discuss the story and decide their approach together? How much communication is involved, and how do deadlines complicate things? When the turnaround time is shorter discussing things ahead of time might not be an option. In such situations, the writer chooses story elements that complement the strengths they see in the artists’ work. But how does the writer determine those strengths, and how can they write a comic that best takes advantage of them?

Below is a guide of sorts which writers can follow to support and empower their collaborators, containing input from five professionals in the comics industry. I’m not the foremost expert on this subject. Even though it incorporates the views of creators who contain that expertise, this piece ultimately one person’s interpretation. But hopefully it’s one that proves useful for readers, particularly writers and artists.

Understand how a collaboration contrasts from a singular vision

A comic created by a writer and artist can never achieve the same singular focus found in works made by one cartoonist. On the other hand, working with another creator produces a fusion of styles and perspectives neither creator could have achieved alone.

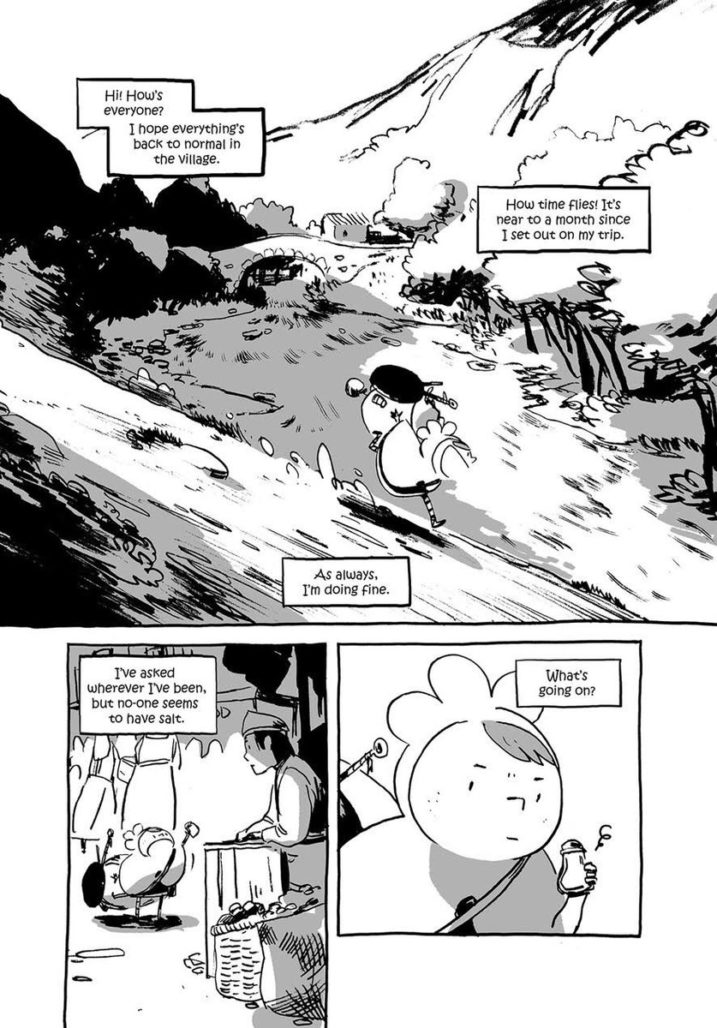

I Kill Giants artist and Umami writer/artist Ken Niimura offers insight into how a comic is fundamentally different depending on if he creates it himself or in collaboration with another writer. Read his explanation of how he believes writers and artists approach a story differently.

I think writers tend to think first in terms of abstract ideas and words (which is something I’m really jealous about), to which they add images they will describe in the scripts. When I do my own stories, I don’t write a script, and work directly on the storyboards. It usually takes more time in the first stages of the project, but this allows me to not just think in terms of the dialogues, but show things in a more direct way using just visual elements, while also working on the pacing. The rhythm and dynamism are the most crucial parts to me, as comics are just the means to reflect an idea on the reader’s mind, and it’s what will make a story and characters feel alive or not.

Niimura describes the struggle to create something that feels cohesive when multiple collaborators are involved:

When you work with someone, you’re also helping bring their ideas to life, so unless you understand them, and – most important of all – agree with them, it can be a real struggle. It’s not just illustrating, it’s being in the same wavelength.

What I like about writing and drawing my own ideas is that I can create an overall concept, and develop it in the script, the dialogues, the character and background design, and even the art. There are many different ways to express the ideas in comics, and this richness and variety is really what makes comics such a rich medium.

Christine Larsen explains how collaboration influenced Boom Studio’s By Night for the better.

[When collaborating on a comic] you have more hands in the pot, which sounds like a bad thing (and, certainly, it always has that potential), but can actually result in something you would not think to do yourself.

I love having Sarah [Stern] color my work in By Night. She makes completely different color choices than I would, yet maintains my line quality and the inherent graphic nature of my cartooning style. That is a colorist in tune with the line artist.

I like getting those By Night scripts, because John [Allison] is definitely a wordy-joke kind of writer, but he also draws, which helps him realize how much text you can squeeze onto a page before it’s too much.

I honestly really like having other people to work with on a project. It makes me feel less alienated. When I do my own stories soup to nuts – though I really enjoy that process as well, and like having control over all aspects of my story – letting go a little can create something larger than its parts. And I find that the work I do with others will feed into my personal work in one form or another.

Mike Norton describes the difference between working alone and with others succinctly and effectively.

I do think there’s a singularity of focus from someone that is doing it all themselves. It’s a clearer vision.

Working with multiple people is an art unto itself and I think collaboration is something beautiful. There’s always an excitement to how something will actually turn out.

Remember that a collaboration is a relationship

A few comic book writers are notorious for considering their role in the creation of a comic finished as soon as they hand in a script. That mindset doesn’t afford them a chance to make adjustments when the art comes in, a disservice to the artist and the art form. It treats the making of a comic like a factory line, where each creator does their work in a vacuum.

Valiant Entertainment and former Marvel Comics editor Heather Antos explains why keeping an open line of communication is key to fostering fruitful collaborations.

With every single project I work on, there is a group email where everyone is able to chime in and brainstorm and create TOGETHER. If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a million times; comics is a team effort.

Just like no champion sports team can be supported by just one player, making great comics takes EVERY member working TOGETHER with a clear vision in mind. For me, that starts with building a strong team dynamic where everyone feels their voice is heard and can play off of one another’s ideas and strengths.

Understand what you’re asking

In my talks with them both Norton and Phil Hester referenced how taxing it is to illustrate scenes filled with characters. A battle between a hundred warriors take seconds to type out, but requires days to draw.

Hester says that, as a writer and artist, he is “distinctly aware of the burdens a writer can put on an artist, and also the ways an artist can fail a script.”

I know it takes a few seconds to type the words “an old-time locomotive engine crashes through the wall of The Louvre, sending the crowd fleeing as the famous works of art are demolished by the impact,” and at least a day or two to draw it.

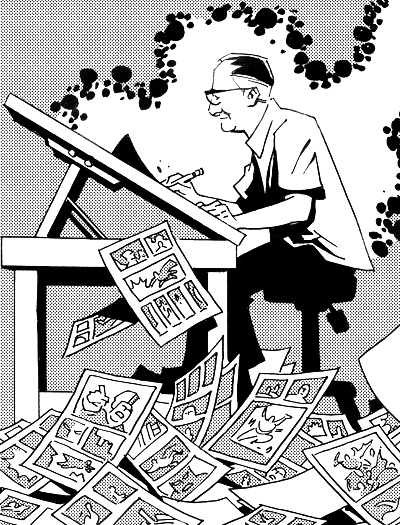

An artist devotes a lot more energy drawing a comic than a writer spends on their script. Even if a story is slow to come together, the writer doesn’t spend all of that time behind a keyboard. An artist, meanwhile, is chained to their drawing board by deadlines.

Reward the artist

Hester suggests that writers, if they really needed to write that crowd scene, script other scenes in the comic that are less taxing and time consuming. He describes it as “rewarding” the artist.

Balance your museum destroying panoramas with a few easier scenes. That doesn’t necessarily mean simpler scenes, but scenes more in tune with the artist’s preferences. For every nightmarishly hard or boring page, reward with two exciting or easy ones.

If you ask too much from an artist, they’ll burn out. Writers need to recognize that, if every page is time intensive, the comic takes longer to make and the artist becomes exhausted and (rightfully) frustrated. They can scenes that don’t require backgrounds, or don’t feature many characters. Another option is to harness the magic of the medium to develop original ways to reduce the artist’s workload.

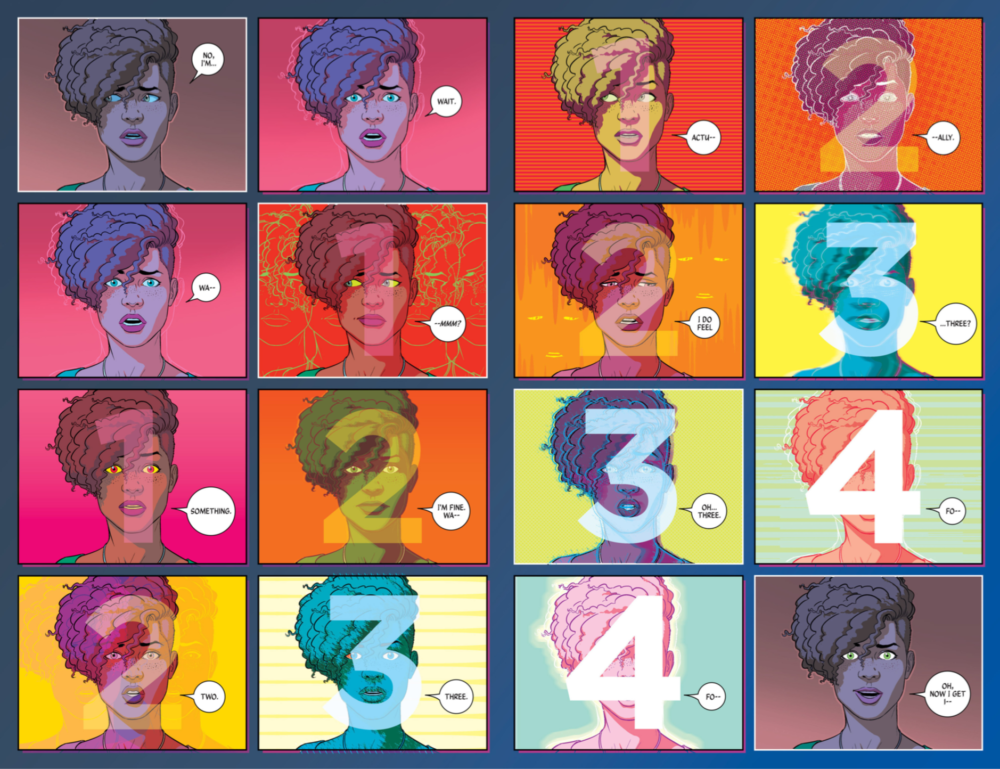

Kieron Gillen invented several unique methods of rewarding an artist while collaborating with Jamie McKelvie. Their comics generally have the same amount of real estate to work with i.e., how much time McKelvie can commit to drawing each issue. In his Writer’s Notes for The Wicked & The Divine #8, Gillen describes writing an issue that demanded more than the regular number pages per issue. To compensate for this, he developed a workaround, scripting scenes that incorporated panels without any illustrations. Thus, Jamie’s workload remained the same.

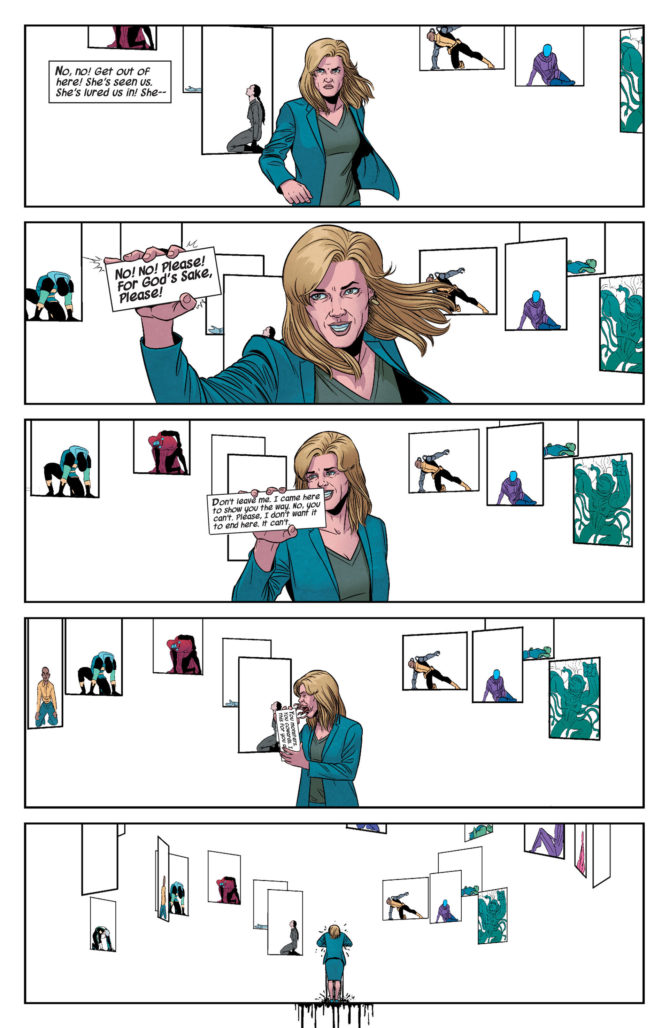

Gillen took the concept of empty space even further a year prior, in his and McKelvie’s Young Avengers series. Mother, the central villain of their 15-issue run, transports the heroes to a dimension of pure white. Gillen managed to devise a terrifying world that complemented Jamie’s adeptness for character work and saved him from hours illustrating backgrounds.

Recognize and write towards an artist’s strengths

Part of writing for artists is, naturally, to identity their strengths and plot stories that play to those strengths. Antos describes her mindset as an editor when pairing an artist with a book.

One of the first things I always ask an artist is, “what do you want to draw?” I’ll also study an artist’s previous work — what are their strengths? Where do they excel? how can we build and write a story for that? Writers will do this too.

Antos points to Deadpool vs. Punisher with Fred Van Lente and Pere Perez as an example of great collaboration:

Fred knew that Pere was a martial arts instructor outside of his comics job. So when it came to writing the fight scenes, Fred simply told Pere, “Here are the important beats we need to hit. Here’s the dialogue. But I’ll let you choreograph the fight — you know better than me.” This mini series is 5 issues of specific examples of Fred playing to Pere’s strengths as a martial artist and a comic artist.

Fred considered not just Perez’s skillset as an artist but also his life background in order to write a comic he knew Perez would excel at drawing.

Larsen has an art style that not all writers understand how to utilize. She dives into how writers should adapt the storytelling based on the artist’s style.

[I]f you are part of a creative team, it is important to look at the kind of work your artist does and see how you can adjust your visual storytelling to match the stride of your artist’s. For example, my work is very cartoony, and though I think cartoons can be used in serious subject matter to great effect, that subject matter must be presented in a way that does not come across as silly or goofy. There are certain kinds of blocking that would not read well in my style, or details that would be awkward in my type of rendering.

I like to be taken out of my comfort zone, which is why I like to work with writers, but I don’t want to alter my visual style to suit a script. Your artist is not a hand to bring your vision to life. You are a team, and whoever you are working with will appreciate it if you do your homework (on their portfolio) before picking them.

Perhaps more important than considering what an artist can do is identifying what they can’t do. There are some types of stories that some artists just won’t excel at, no matter how talented they are.

Hester warns that, while writing to an artist’s strengths can lead to great comics, it carries the risk of leading to typecasting. He says that some of the best comics are a result of creators stepping outside of their comfort zones. Keeping artists inside that bubble might limit their potential.

One method to avoid typecasting is looking for strengths deeper than what the artists draws well. Consider the artistic sensibilities that inform the art styles. Determine what artists bring to their work that’s difficult to explain, because that’s often the thing that’s the most special.

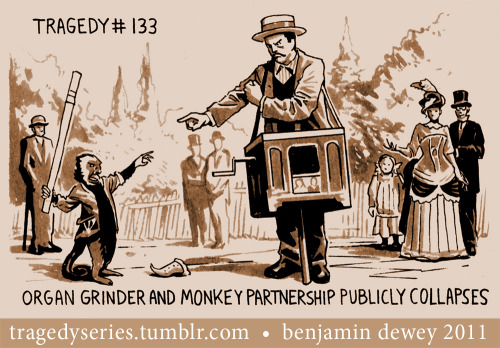

Ben Dewey draws adorable and expressive animals, which is why he’s hired on titles like Autumnlands and Beasts of Burden. But a sense of whimsy is at the core of his art. His Tragedy Series strips demonstrate that, and literally illustrate he also draws humans excellently. Therefore, a writer working with Dewey may want to focus on humor over the appearance of talking animals.

Ask what the artist wants from the experience

It helps both collaborators to touch base, so the writer and the artist know what to expect from the project and to avoid potential pitfalls.

Brian Michael Bendis has mentioned falling into one of those pitfalls at the beginning of his New Avengers run. He describes scripting complex panel layouts for David Finch to draw and only realizing later that the artist wanted to focus on the illustrations rather than experimenting with his storytelling. That misunderstanding resulted in an experience neither was fully happy with.

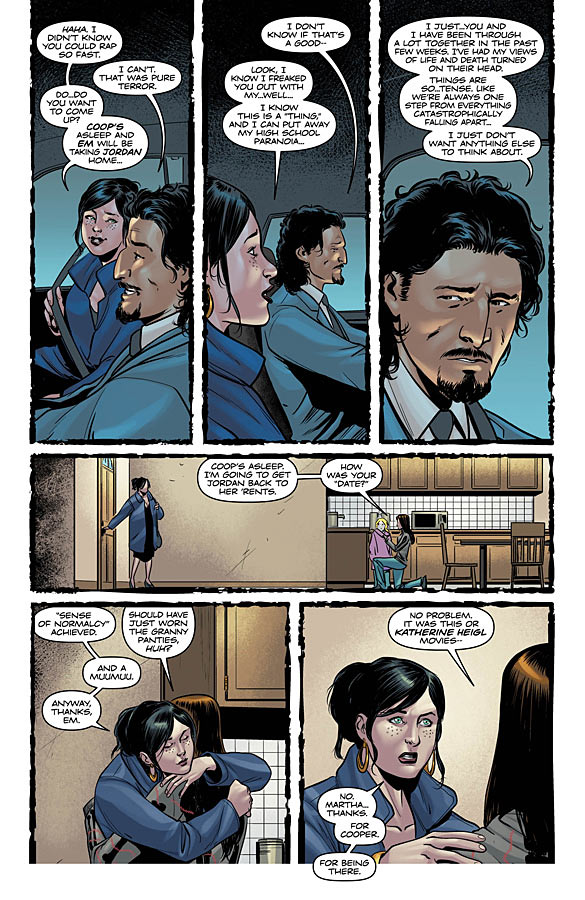

Whenever possible, writers should ask artists what they like and dislike drawing. Mike Norton says his collaborators write scripts they know he’ll enjoy working on.

I get a lot of the talking stories! I enjoy characters acting, and I think I get a lot of that. I don’t get a lot of the “superhero battling in space stories”. I don’t think it’s because writers think I can’t draw that, but they know I’m better at the other stuff.

Not only is it kind to tailor a script towards what makes the artist happy, it tends to result in a better comic book. If an artist hates drawing vehicles, they’ll feel drained illustrating a comic set in an urban city. A creator’s dedication to a project is proportionate to their excitement about it. Keep the artist enjoying the collaboration so they’ll deliver their best work.

Remember that an artist does more than draw

Let artists be storytellers, not art monkeys, so don’t overdirect. Drawing breakdowns is a key part of the artist’s role in making the comic, don’t take that from them.

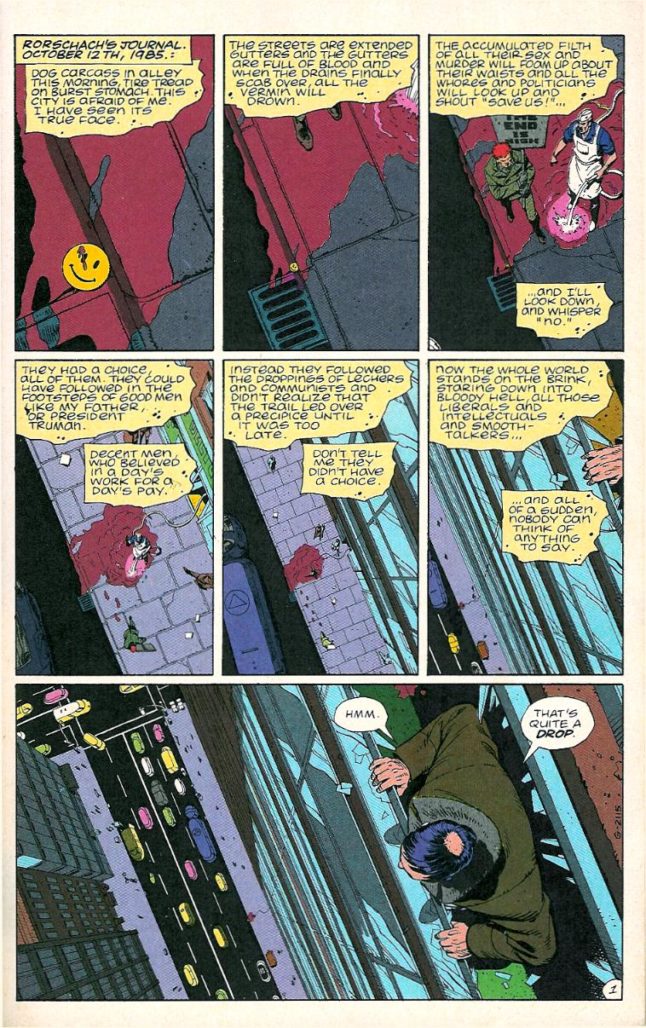

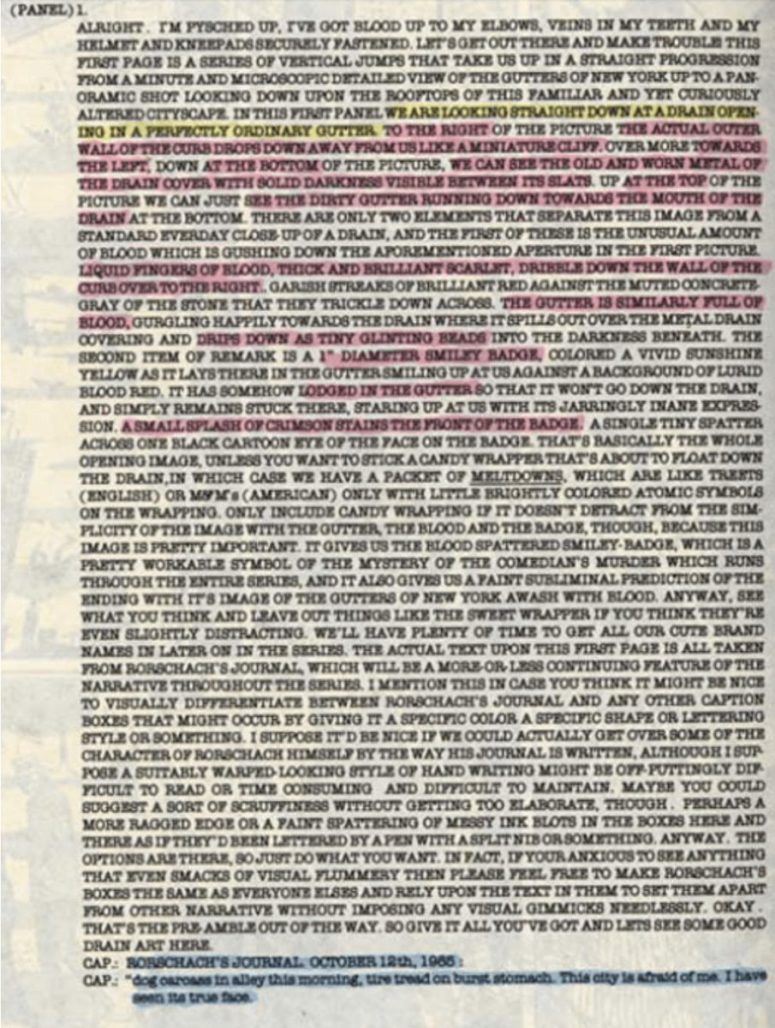

Scripts with long, hyper-specific descriptions are largely unnecessary and frustrating for the artist. Everyone mentions Alan Moore’s very detailed scripts, but it’s important to point out that many artists identify what they need to draw and essentially ignore the rest. See how Dave Gibbons highlighted what was relevant in Moore’s description of Page 1, Panel 1 of Watchmen.

Sometimes there’s a valid reason for being more detailed, such as a dedicated panel structure. For example, Watchmen and many of Tom King’s works rely on the 9-panel grid for pacing. But something like that is ideally discussed with the artist before pencil meets paper.

In Niimura’s words, the best scripts for an artist are “inviting, stimulating, and exciting.” He explains how his manga background made him accustomed to more decompressed storytelling, and how he has to adjust on Western comics, and how the writer needs to adjust to his art style.

Among the many limitations that come with a project, there is also the format given to take into account. This will probably also dictate the number of pages you have, which is where you might have a little struggle trying to fit everything. Manga has in that sense more room for big panels and letting the scenes breathe.

In order to achieve a similar pacing in his Western comics, he works with the writer to adjust the page count and what appears in each page as needed.

Hester quotes Neil Gaiman, who describes a comic script as a 10,000 word script to the artist. Hester says a script should be conversational, not dictatorial. Which sounds fitting for what should be a relationship between the writer and artist.

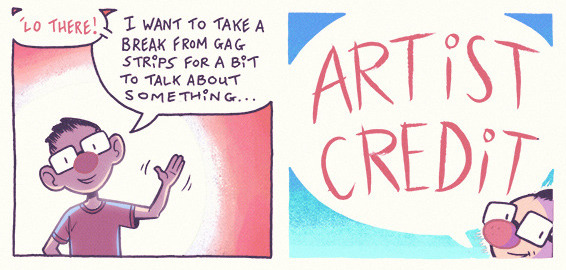

Credit the artist adamantly

The hostility around the circular “writer vs. artist” debate would very likely ease up if artists received proper credit in the industry. There are a lot of reasons they don’t. Among them, Hollywood trades seem unwilling to describe a comic as a work of multiple creators, and the biggest comic book publishers often title their trade paperbacks based on the writer.

Whether the lack of credit it due to malice, ambivalence, or purely by happenstance doesn’t matter much. What matters more is that it isn’t equally shared. Artists are rightly angry that they don’t receive the recognition they deserve for their work.

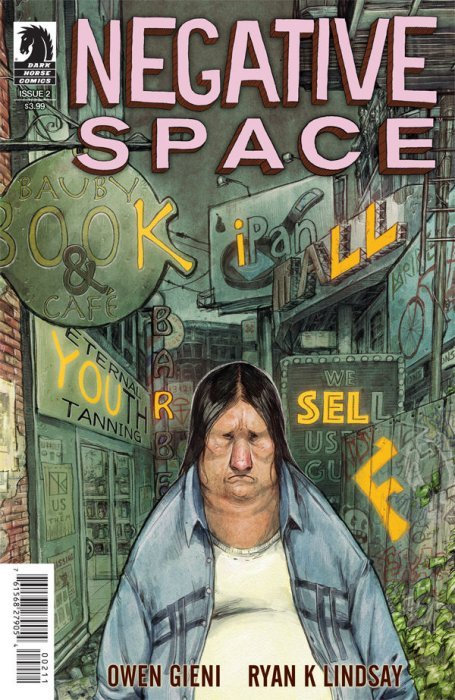

The best thing a writer can do is be local about the artist’s role in their work. Ryan K. Lindsay lists the artist’s name first in the credits of his comics. Other writers might fear that doing the same will suggest the artist co-wrote the comic, or that the writer’s role is in some way diminished. But, since artists don’t receive the respect they deserve, writers carry the responsibility to change that.

That’s not even much of a burden. Making sure to mention the artist when discussing the comic in an interview or on social media is a start. Writers also need to avoid tacit endorsements. They should pause before linking to an article that doesn’t give credit to the artist. If they decide to promote it anyway, writers can at least note that the comic was a collaboration when they share it.

Maybe someday the writers/artists discussion won’t result in hurt feelings. Both should be proud of their contribution to comics neither could have created alone. To end on a positive note, read how Niimura beautifully describes writing for an artist.

In the best of cases, it means knowing what your artists is best at, and adapting the script to bring forward that aspect.

I’m currently working on a new project with Joe Kelly, and although the script is done and solid, we are going to decide the number of pages we use for each scene as we work along, to give each one the space and pacing it needs. We might add panels, we might take some, we might add pauses and sceneries, but it’s all in the project’s best interest. We’ll discuss, modify and adapt. We might not always agree, but that is what “write for your artist” really means to me, to engage in a creative conversation.

Just as artists writers have to improve their skill of writing everyday, also we need to understand that for the most part those are the part-time project, in order to have enough money on life writers and artist often work at few projects at the same time. It’s a common thing when writers also have a part time editing jobs and write stories for comics as their hobby at free time. I hope that platforms like patreon gonna resolve that problem soon.

Comments are closed.