FX and Noah Hawley will debut their new semi-X-men television drama Legion on Wednesday, February 8th at 10 pm. Though it is too soon to tell if the series will be an ongoing hit or will go the way of Greg the Bunny, the question remains: who is Legion — and why make a television show about him?

First appearing in a shocking epilogue at the end of Claremont and Sienkiewicz’s New Mutants #25 (1985), Legion was David Haller, the previously unknown son of Professor Xavier and Gabrielle Haller, Chuck’s Israeli ex-patient/girlfriend who first appeared in the iconic Uncanny X-men #161 (1982).

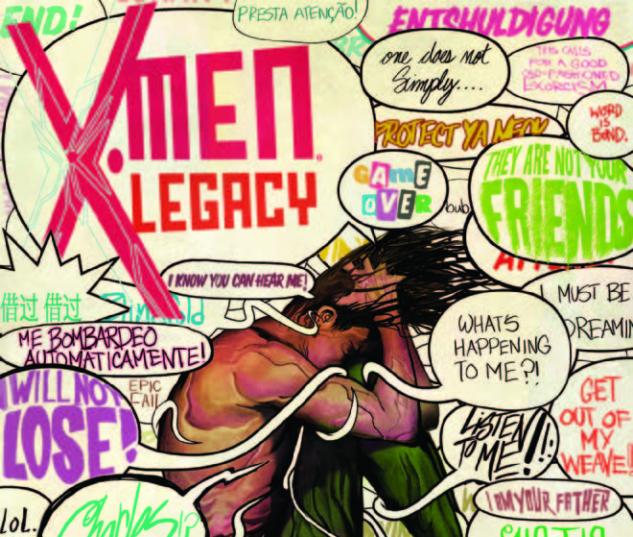

Legion was characterized by a wide net of pop-Star Trek-psych disorders, including autism, schizophrenia, and multiple personalities – each with its own distinct mutant power. Though this smacked a little bit of DC’s Dial H for Hero, it was still a new twist for the X-men. Legion has appeared intermittently since then, more often a necessary villain than not.

The subject of multiple personalities was a popular one in the eighties. In comics, Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz’s 1980 relaunch of Moon Knight showed Marc Spector’s various “identities,” each with their own skill set. Mike Baron’s The Badger at Capital Comics (1983) chronicled the misadventures of Vietnam vet Norbert Sykes, who had numerous personalities including a costumed crimefighter, an architect, and a dog. He also called everyone “Larry.” The Badger’s condition was due to trauma he suffered as a child from his step-father and step-brother, both white supremacists.

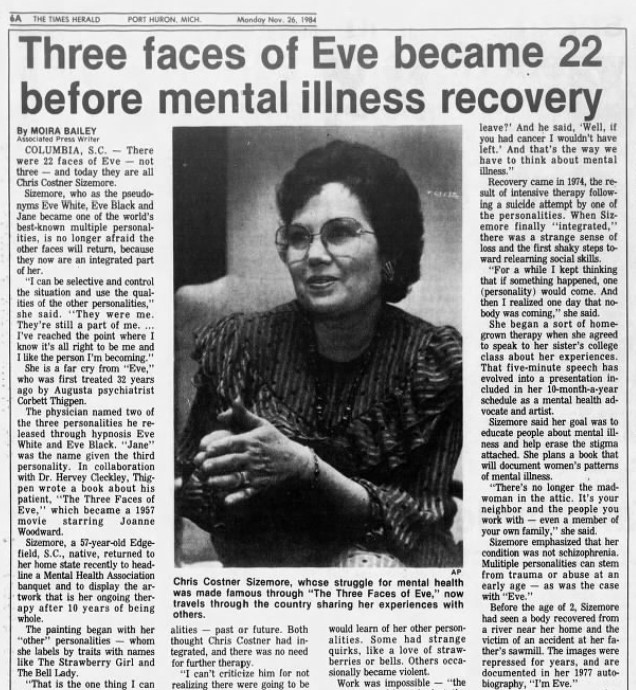

A popular case of multiple personality disorder in the real world was seen in Three Faces of Eve, a 1957 movie with Joanne Woodward based on a book by psychologists about their own patient, a woman named Chris Costner Sizemore, who eventually manifested 22 personalities. In the comics, Legion at one point boasted — at least — a robust 1,102. Sizemore’s personality allegedly fractured when she saw a dead body as a child. In the comics, Legion’s mind is split when he lives through a Palestinian death squad’s assassination of his step-father. Legion then absorbs the psyche of one of the young Palestinian killers — who then works with David, and the New Mutants, to unify his mind. This is high Claremont drama with a political twist — all made semi-believable through the instant group dynamic of multiple personalities. Woodward won the Oscar for Three Faces of Eve.

Also popular was the story of Sibyl, the pseudonym of the 1973 bestselling book about a woman with sixteen separate personalities. It was made into a popular TV miniseries starring Sally Field and an apparently-typecast Joanne Woodward. In 2011, the real Sibyl, Shirley Mason, admitted that she had made it all up.

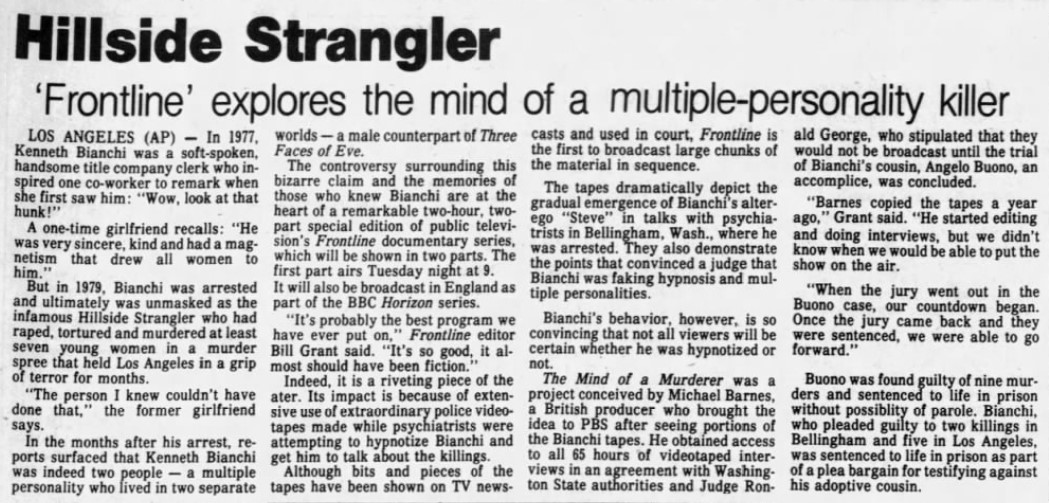

Villains were also given the diagnosis of MPD. Kenneth Bianchi, known as the Hillside Strangler, killed twelve (and probably more) Los Angeles women in the late seventies with his cousin. When Bianchi was finally caught, he pleaded MPD with two separate personalities. Frontline on PBS ran a two-hour documentary on Bianchi’s diagnosis with shocking videotape recordings. The show ran in 1984, a year before David Haller’s debut.

Multiple personalities had become so normalized that they even appeared in soap operas.

Some of us may or may not have wanted to admit it back in the eighties, but that’s what the X-men really were anyway. Lynda Hirsch could just have easily written capsule summaries of New Mutants Annual #2: Mojo kidnaps Betsy as Dani gives Doug a much-needed pep talk. Bobby dies in a tragic accident, but Warlock thinks otherwise. Magik takes them to the Mojoverse. Doug dangerously merges with selffriend Warlock, saving a grateful Betsy. Sparks fly between teenage Doug and the much-older Betsy.

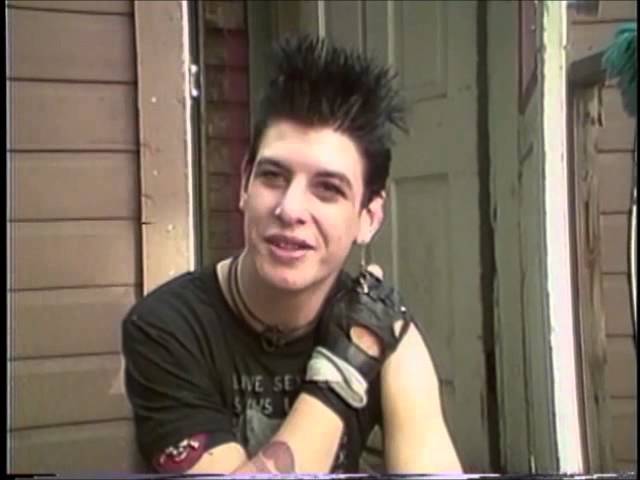

Though Legion was probably indebted to all this pop multiple personality thinking, his character design doesn’t really fit Sybil or Eve or Ryan’s Hope. Not that readers expected that, but when we saw Legion, we saw, consciously or not, almost the exact opposite. We saw punk.

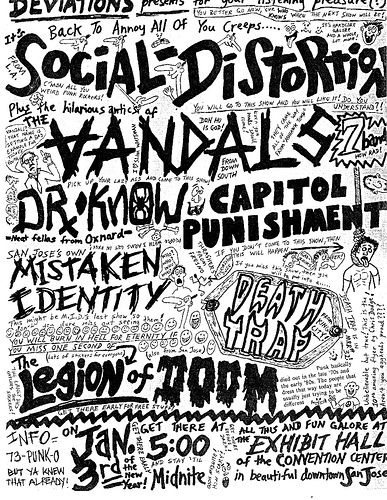

Storm had sported a mohawk earlier in Uncanny, so we knew it could fit in with the X-men universe. Legion had abnormally spiked hair, cut-off clothes, and was really thin and lanky. He looked like Mike Ness of Social Distortion scratched onto a Bristol board by Bill Sienkiewicz.

Punk, in fact, might be helpful to understand why they picked Legion for a TV show, instead of, say, Fantomex or Martha Johansson. Legion was unpredictable, raw, and sometimes burned it all down when his pyrotic personality, the punk rocker Cyndi, took over. Plus, David was a troubled kid whose parents split up. He was well off, but he had an axe to grind, especially with his dad. He was classic punk. And “punk” referred to a general collective, a youth movement. Like, in its best moments, “mutant.”

The early eighties was punk personified. Even if you didn’t listen to it, The Clash was on MTV every twenty minutes, singing/shouting about something in the Middle East. Punk, and its icons, were often described as just “crazy.”

Legion seemed to be a fusion of a serious mental disorder with the destructive fantasy of take-your-shirt-off-and-scream punk. Whether or not the new show addresses any of these points is unknown. But at least we can see — maybe — where they are coming from. In the new show, it seems that multiple personalities have been swapped out for a more general pop schizophrenia and punk rock in favor of trance with beanbags and mauve. Either way, it’s the balance of mental illness with youth. Crazy kids.

“Crazy” is a trigger word now, but equating mental illness with mutant powers has the possibilities for some powerful storytelling. At the same time, the problem with the old Legion stories in the comics is that they almost always ended the same way. They were never as good as Magneto or Belasco stories. Xavier always promised to cure his son, but he never really did. That was always okay with Ben Grimm (we didn’t really want to see “It’s pilotin’ time!”), but this kind of ending takes on a different echo when it’s about mental illness. Though the X-men were, and remain, one of the best fictional and cultural American metaphors for the outsider, their depiction of mental illness is harder to understand as positive. Legion, Proteus, and even (especially) Jean — none of those stories end very well.

Whether Legion attracts kids with its oversized headphones, peppers the nerds with Easter Eggs about Muir Isle, or gets to tell new stories about mental illness based on the core belief of the X-men — that difference is power in a world that hates and fears you — we’ll all see soon.

Brad Ricca is the author of the new book Mrs. Sherlock Holmes and of Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel & Joe Shuster – The Creators of Superman. He also writes “Luminous Beings Are We” for StarWars.com. Follow @BradJRicca.